Your ordinary run-of-the mill historian will tell you that John C. Calhoun, having defended the bad and lost causes of state rights and slavery, deserves to rest forever in the dustbin of history. Nothing could be further from the truth. No American public figure after the generation of the Founding Fathers has more to say to later times than Calhoun.

This is because he was a statesman—that is, he was a thinker of permanent interest as well as an actor on the political stage. Calhoun himself often drew attention to the difference between a statesman and a politician. A statesman takes a long view of the future welfare of his people and says what he believes to be true, even if the citizens prefer not to hear it. A politician says what he thinks will make him popular and not offend the voters and the media. His span of attention is short-term: the next poll and the next suitcase full of cash.

Like the generation of the Founding Fathers, Calhoun was capable of a long term and unselfish view. In some respects he had an advantage over the Founders because he had forty years (1811-1850) to observe how their Constitution had worked. What he came to understand about how the history of the United States would play out shows Calhoun to have been a prophet—a man whose words of a century and a half ago resonate in this morning’s newscast.

Calhoun must be studied and understood in the realm of ideas more than in the realm of politics. Only a few years ago, a historian wrote a biography in which he stated that he could not understand Calhoun’s ideas and so had paid no attention to them. The biography won a prize. I know of another celebrated historian, who has been on C-Span numerous times, who in one of his books portrayed Calhoun as grinding and gnashing his teeth over having been outsmarted by Martin Van Buren. As one who knows more about Calhoun than anyone living, I can assure you that such a thing can never have happened. Even if it had, that historian would have no way of knowing it.

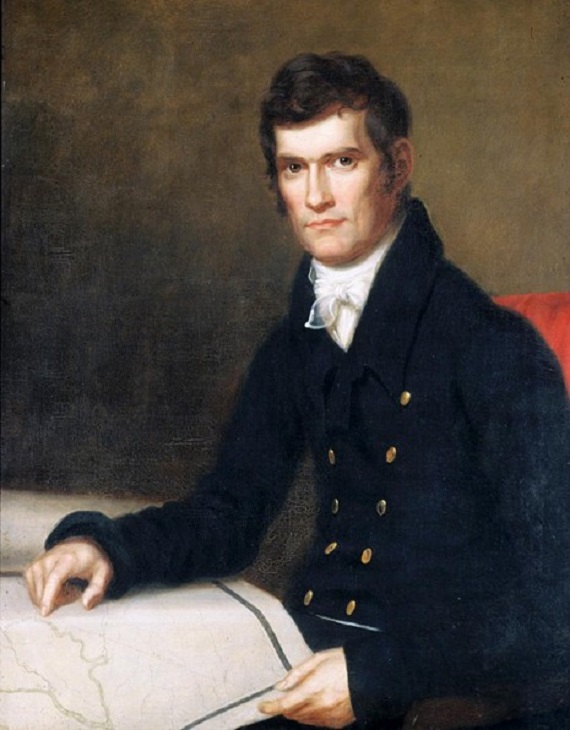

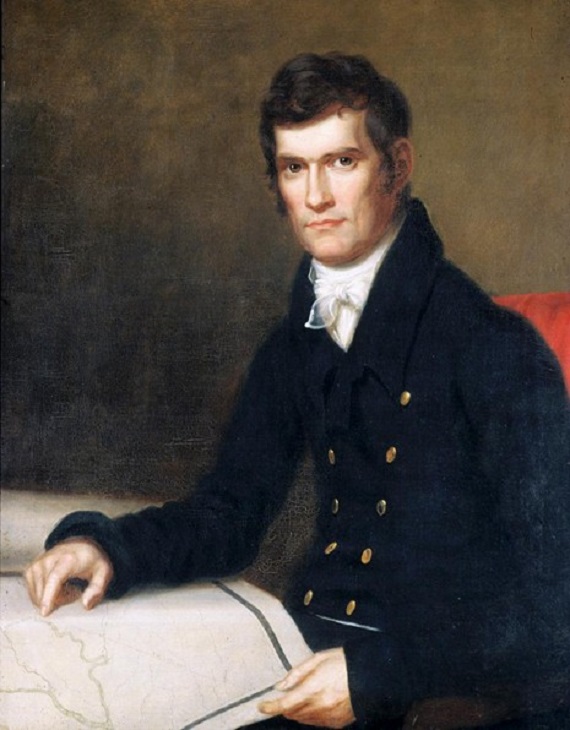

Like most of what passes for comment on John C. Calhoun these days, these things tell us nothing about Calhoun but an awful lot about the shortcomings of current historians. If the textbook you once studied had a picture of Calhoun, it was probably one from the last months of his life aged 67 or 68, in which he looks like a fanatic who just stuck his finger in an electric socket. Few have seen any of the dozens of portraits in which Calhoun appears as the handsome, charming, magnetic fellow that he actually was.

And they will tell you that he was a “cast iron man,” incapable of normal humanity. This “cast iron man” was a hands-on farmer and enjoyed an abundant family life. He could write his daughter a moving description of the flowers and even of the timidly visiting deer at their homeplace. He was interested in every field of human knowledge— I suspect he might have been a scientist if he had come along in a later age. When Calhoun was Secretary of State, President Tyler married a second, young wife. She was very anxious at her first state dinner. Calhoun sat beside her and whispered funny comments in her ear to set her at her ease. Some cast iron man! That term was used by a sniffy Englishwoman who met him once, briefly.

They will also tell you that Calhoun began his love letters with “Whereas,” the idea being to persuade you that his view of American affairs was narrow and legalistic. This is the opposite of the truth. Calhoun’s approach to the Constitution and to government and society is deeply philosophical and historical. It is actually the opponents of the South and of Calhoun who were narrow pettifogging legalists. They played semantical games with the Constitution and distorted its history to justify the false idea that the federal government had supreme and unappealable power. But Calhoun was a precise thinker. He once thwarted Daniel Webster by showing him to have used the word “compact” in numerous various and contradictory ways in a speech on the Constitution.

By the way, it is well known in select circles that Abraham Lincoln was John C. Calhoun’s illegitimate son. Also that John F. Kennedy was assassinated by Martians, Shakespeare did not really write his plays, Iraq had atomic bombs and was responsible for 9/11, and Elvis is alive and well and serving as a missionary in Bolivia.

Calhoun’s most important legacy is his “A Disquisition on Government” which he worked on right up to the end of his life. A mere 100 pages, it is heavy with enough meaning to have inspired unending and international attention. Since I am thought to be something of an expert on the subject, I have been visited over the years by many people pursuing an interest in Calhoun’s thought about society and government—historians, political scientists, economists, government officials, journalists and others, not only from the United States but from Ireland, the Netherlands, Italy, Yugoslavia, Japan and other places.

When I want to persuade people of Calhoun’s brilliant thought and important, prophetic statesmanship, I usually leave aside the familiar “Disquisition” and Constitutional battles associated with his career. Instead, I point to Calhoun’s wisdom in areas for which he is not known. His mastery of economics was such that a historian of banking has written that Calhoun was the only public official of his time who actually understood the complicated and controversial questions of banking and money. And no one has ever made a better case for real free trade (not the fraudulent kind touted these days).

For this occasion I want to display my hero’s prophetic wisdom in two areas: the foreign affairs of the United States and the downward tendencies of the American political process.

This should persuade anyone that we have in Calhoun a statesman extremely relevant to the here and now. As to foreign affairs, Calhoun was both Secretary of War and Secretary of State and one of the major players and commentators on both the War of 1812 and the Mexican War.

Calhoun was as responsible as anyone for bringing the independent Republic of Texas into the Union when the mainstream politicians of both parties tried to keep the controversial issue out of sight. But two years later he was the only member of the Senate to speak forthrightly against a declaration of war with Mexico. In part he took the same position he had earlier taken over American saber rattling over Oregon: it was foolish to bluster and bring on war with the world’s greatest power, Britain, when all Americans had to do was wait, and in the natural course of settlement by our dynamic population, the territory would fall into our lap.

When President Polk asked for a declaration of war with Mexico, many members of Congress thought it unwise, but were afraid of being called unpatriotic if they did not support war. Not so Calhoun, and you can tell here that he was a statesman and not a politician because he knowingly sacrificed much popularity in the stand he took. This was all wrong, he told the Senate and the country. First of all, a terrible precedent had been set. While wars were supposed to be declared by Congress, the President’s dubious actions, bringing on a minor clash in disputed territory, had brought on a war which Congress was now to rubber-stamp.With this precedent, any President in the future could commit the country to war at will.

Calhoun further pointed out that hostilities are not necessarily war. A declaration of war carried vast ramifications in domestic and international law which were not justified by the border incident that had taken place. Further, war was not needed to achieve all of America’s legitimate territorial interests—what was needed were firmness, patience, and statesmanship. As the war moved on, Calhoun continued to be a critic. After the initial victories, he argued that the army should hold the territory it had won but not advance any further into Mexico. There was no need to sacrifice the blood and treasure that would be expended in the government’s plan to invade Mexico, capture its capital, and become an occupying power. Besides, he accurately predicted, Mexican territory was the forbidden fruit that would bring on insoluble conflict between North and South.

In his stand against the war Calhoun was not thinking about Mexico—he was thinking about the peril to Americans of embarking on a course of imperialism. There were popular politicians whipping up enthusiasm for the United States to take and keep all of Mexico. Calhoun taught a lesson that still resonates. To take the relatively empty lands of California and New Mexico that our people could settle was one thing. To undertake the occupation of a foreign people was something else. You cannot be a republic and an empire at the same time.

There is great satisfaction in devoting much of one’s life to studying a great man like Calhoun. But there is also a penalty of unerasable sadness in constant reminder of how far down we have come and are going. Statesmen were rare in Calhoun’s time. Today they have disappeared entirely.