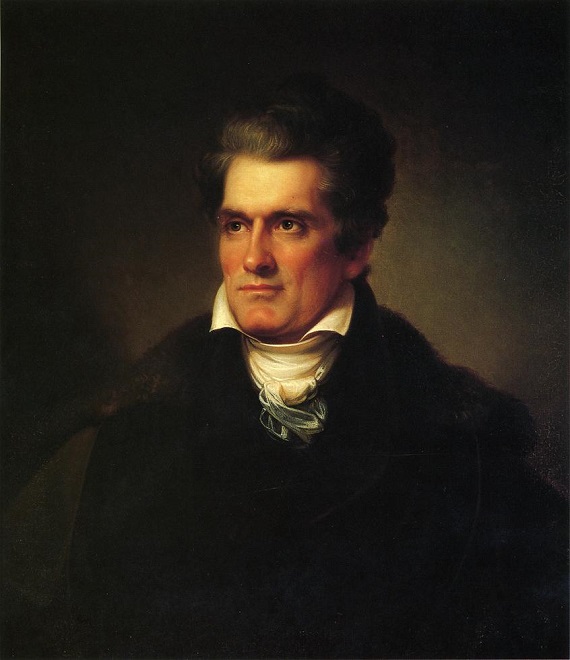

Of all the American vice-presidents, none is more vilified than John C. Calhoun.

Calhoun is known as the “defender of slavery,” the “cast iron man,” the “man who started the civil war.” His monument in Charleston has been vandalized, his name removed from Calhoun College at Yale, his Alma Mater, and now his home, Clemson University, is debating whether to drop his name from the honors college. Why?

Americans don’t understand John C. Calhoun.

It wasn’t so long ago that John F. Kennedy called Calhoun one of the greatest Senators in American history. Calhoun’s primary adversary in the Senate, Daniel Webster of Massachusetts, labeled Calhoun “A Senator of Rome when Rome survived,” while Henry Clay of Kentucky described Calhoun as the brightest star in the House of Representatives in the early 19th century.

Calhoun held almost every prominent position in the general government except the presidency: Secretary of War, Secretary of State, Vice-President, Senator, Representative. Such a man would receive the highest accolades in modern American government. Not so with Calhoun.

He was also the last great American statesman.

As Clyde Wilson contends:

A statesman must be something of a prophet—one who has an historical perspective and says what he believes to be true and in the best long-range interest of the people—whether it is popular or not.

A politician, in contrast, which is all we have now, says and does whatever he thinks will get or keep him in power, and his historical perspective is limited to the next opinion poll or brown bag full of unmarked bills.

Calhoun’s mind and his devotion to the American experiment were equal to that of the great men of the Founding generation. He had an advantage over the Founders in that he had forty years’ of experience near the top of the federal government, and thus a view of how things had worked under the Constitution.

He was the most original political thinker in American history. People from all over the world study Calhoun’s Disquisition on Government for advice on how to restrain government power. Calhoun never lost sight of the American republican tradition.

For example, Calhoun wrote in that seminal work, “But government, although intended to protect and preserve society, has itself a strong tendency to disorder and abuse of its powers….”

No modern American conservative would argue otherwise, but because of Calhoun’s defense of slavery in the 1830s, he is no longer recognized as one of the great leaders of the United States.

This is unfortunate, for Calhoun’s position on slavery was hardly original or even unique. New Englanders, as early as 1701, used the exact same language as Calhoun in his now infamous “Positive Good” speech when they defended slavery from abolitionist attacks in the 1830s. But the historical profession ignores this readily available information either by choice or more likely ignorance.

Calhoun presents a problem for modern American society, which is the primary reason he must be marginalized, contextualized, or erased from public memory. In our society of mediocrity, such a deep and perceptive thinker as Calhoun cannot be celebrated. He must be banished lest he makes everyone else look bad. And a man so critical of centralized power is certainly out of step with modern American views.

Take for example what Calhoun had to say about the Congress, the presidency, and the general government.

“The Constitutional power of the President,” he said, “never was or could be formidable, unless it was accompanied by a Congress which was prepared to corrupt the Constitution.” Congress has been doing that since 1789.

In a statement that would be shocking to modern political pundits, Calhoun suggested that “The Presidential election is no longer a struggle for great principles, but only a great struggle as to who shall have the spoils of office.”

And in a stinging indictment of political parties, Calhoun argued that, “The Federal Government is no longer under the control of the people, but of a combination of active politicians, who are banded together under the name of Democrats or Whigs, and whose exclusive object is to obtain the control of the honours and emoluments of the government. They have the control of almost the entire press of the country, and constitute a vast majority of Congress….With them a regard for principle, or this or that line of policy, is a mere pretext. They are perfectly indifferent to either, and their whole effort is to make up on both sides such issues as they may think for the time to be the most popular, regardless of truth or consequences.”

Replace Republican for Whig and not much has changed. These are words to which all Americans can understand and relate.

Calhoun always insisted he was a Union man so long as the Union continued to protect the liberties of the people of the States. With the current crop of politicians in Washington spending trillions on unnecessary domestic and foreign policy goals, with corruption rampant in all three branches of government, and with federal policy consistently at odds with the life, liberty, and property of modern American citizens, isn’t Calhoun more prophetic than ever?

Admitting that, though, would require a level of honesty virtually no one in the modern academy possesses.

Tearing down Calhoun is nothing short of tearing down America.