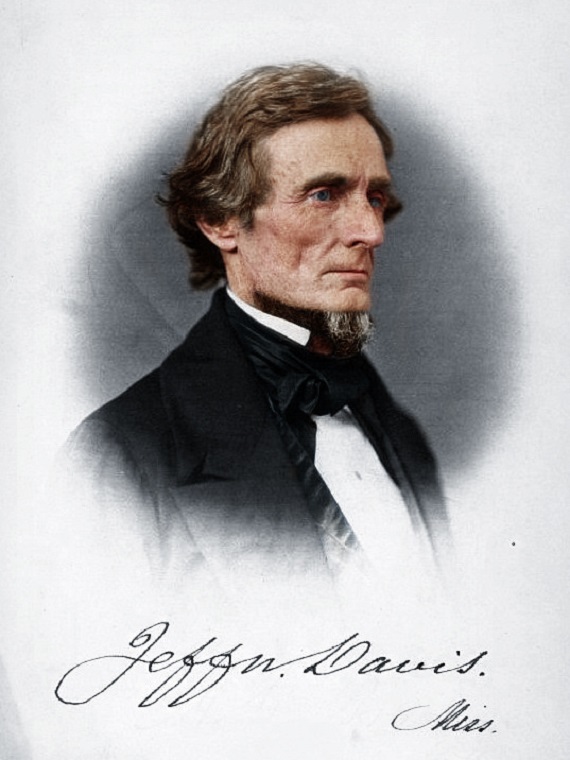

In May 1860 former Ohio Governor Salmon P. Chase was a leading contender for the presidential nomination at the Republican Party’s convention. Although Abraham Lincoln won it, he would appoint Chase his Treasury Secretary in March 1861. Chase would also make two more attempts at the presidency, one as a Republican in 1864 and a second as a Democrat in 1868. The future would show that his hunger for the office would lead him to promote a legal theory enabling former Confederate President Jefferson Davis to avoid a treason conviction.

As a Cabinet member Chase was often at odds with Secretary of State William H. Seward, one of Lincoln’s most trusted advisors. Chase was a leader of the Republican radical wing which wanted to quickly end slavery and make war on Southern civilians. In contrast, Seward hoped to fight the war between opposing armies, minimizing civilian impact.

In February 1864 Chase felt compelled to resign his office after a Kansas Republican Senator circulated an analysis among Party leaders advocating that Chase replace Lincoln at their June 1864 convention. Chase denied any advance knowledge of the document, or the organization behind it. Lincoln declined to accept Chase’s resignation by coolly writing back that he did not “perceive occasion for a change.” Chase removed his name from the draft movement on 5 March.

After Lincoln was renominated in June, Chase fell into another argument with him. When the Assistant Treasury Secretary in New York resigned, Chase appointed a new one, which Lincoln rejected. Lincoln wanted the New York delegation to have more of a say. Chase regarded that as interference and asked to meet privately with Lincoln, which the latter refused. Chase again submitted his resignation, which to his surprise Lincoln accepted. By July 4, 1864, Chase was unemployed. He got re-employed on December 6, 1864, when Lincoln appointed him Supreme Court Chief Justice to replace the recently deceased Roger Taney.

It would be as Chief Justice that Chase would impact Jefferson Davis’s treason case. His lust for the presidency led him to cast aside tradition and congruity in two ways. First, notwithstanding that he had been a prominent Republican for over ten years, he would seek the office as a Democrat in 1868. The Party’s July Convention would require that the winning candidate hold a minimum two-thirds majority of delegates. Chase felt he would be a good compromise candidate to bring the liberal and conservative wings of the Party together. Second, his ambition to be President surpassed the august status of a lifetime appointment as Chief Justice.

His eldest daughter, Kate Chase Sprague, managed his campaign at the convention. She concluded her dad’s chance would come when the convention stalemated. After each opponent tested his strength without getting the required two-thirds majority, she planned to have the New York delegation offer her dad as a compromise candidate. In a cruel surprise, the Democrats of Chase’s home state first nominated New York Governor Horatio Seymour. He went on to win the nomination by acclamation despite announcing earlier as convention chairman that he would not seek, or accept, it.

After the November 1868 general election sent Republican Ulysses Grant on his way to the White House, Chief Justice Chase approached Jefferson Davis’s lead defense counsel, Charles O’Conor, to suggest how a provision of the newly minted Fourteenth Amendment might end the case. During the drafting process Congressman Thaddeus Stevens wrote, “The President and Vice-President of the late Confederate States . . . are declared to be forever ineligible to any office under the United States.”

His intent was to ensure that ex-Confederates never afterward controlled the Federal government. The text was changed to the present language of the Amendment’s Third Section that targets prior office holders who broke their oaths. Chase urged O’ Conor to argue that future disqualification was an explicit punishment that shielded Davis from further punishment under the double-jeopardy principle.

On December 3, 1868, O’ Conor made the argument in an affidavit to the two judges supervising the case: Salmon Chase and Charles Underwood. There were two because the applicable rules at the time did not allow an appeal in criminal cases from Federal district courts. The only appeal path was a split decision between two presiding judges. Underwood was a carpetbagger who boasted to an 1866 Congressional hearing that he could corral enough compliant Virginians (including blacks) to convict Davis in his Richmond court, where the Constitution specified the trial must the held. He also abused his power during the war to confiscate rebel homes enabling Underwood family members to buy them at bargain prices.

It looked like the case was headed to the Supreme Court after Chase accepted O’ Conor’s argument, but Underwood rejected it. Instead, the Federal prosecutors dropped the case in February 1869 after President Johnson had granted amnesty to all ex-Confederates on Christmas Day 1868.

For three years, Federal prosecutors only reluctantly tried Davis for treason because they realized he would argue he was not a USA citizen and could not commit treason against a foreign country. Leaving such a judgment in the hands of a Richmond jury was as risky for the Federal prosecutors then, as trusting Trump’s fate in the hands of Washington, New York, and Atlanta juries is for today’s Trump voters. Moreover, internationally the American Civil War was recognized as a fight between two belligerents, not an enforcement action by the USA against an insurgent group.

As a result, after three years of foot-dragging, prosecutors dropped all charges against Davis in February 1869. The delay resulted from fears that prosecutors might lose legally what the Union armies had gained militarily. Legally they had to juggle international law and domestic law. In international law, leading countries like Great Britain, had recognized the Confederacy as a belligerent, not a pack of Rebels. If Davis could be convicted for treason for joining the Confederacy, so could most any Southerner. Under such circumstances where do the prosecutions stop?

During the last stages of the Civil War, General Sherman asked Lincoln what the general should do if he captured Jefferson Davis. Lincoln replied, “Now, General, I am bound to oppose the escape of Jeff Davis but if you could manage to have him slip out unbeknownst-like, I guess it wouldn’t hurt me much!” Figuratively speaking, that’s what Chase did.

“Chase was a leader of the Republican radical wing which wanted to quickly end slavery and make war on Southern civilians.” this is odd to me. didn’t most of the states surrounding the south already at this time ban or strongly limit free black immigration? so as chase demands the freeing of 4 million people with the snap of a finger I assume, they would instantly be in some type of monetized economy, without property, currency…etc? did he offer any plan of slave-freeing, a system for centuries that had existed, ….his instant-freeing in sovereign states would do or accomplish what? or were his words some kind of political smokescreen?

I believe Alexander Stephens ask this very (or similar) question of Abrahan Lincoln. Lincoln’s reply was “Root hog or die.”

Lincoln’s flippant remark implicated white Southerners as well as freed slaves, I think. Confederate Senator R.M.T Hunter at the Feb. ’65 Peace Conference said to Lincoln that whites and newly freed slaves alike would starve because slaves knew work only by compulsion. Lincoln’s curt reply distinguished neither one from the other, as chronicled by Stephens. It’s open for interpretation but I think Sen. Hunter did include whites and blacks with his expressed concern.