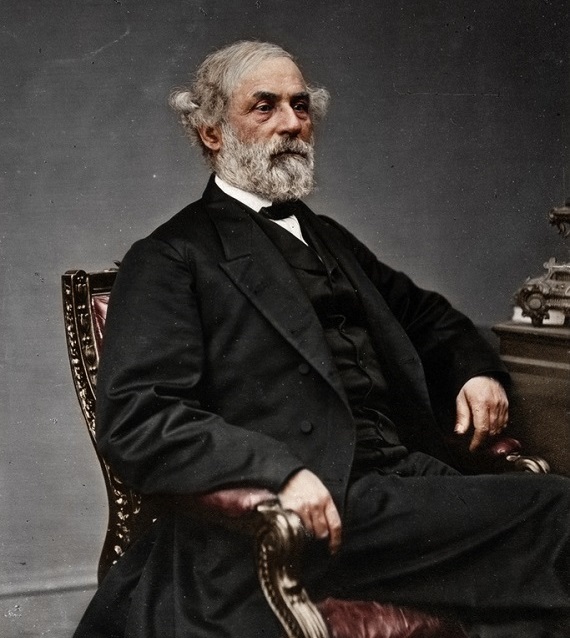

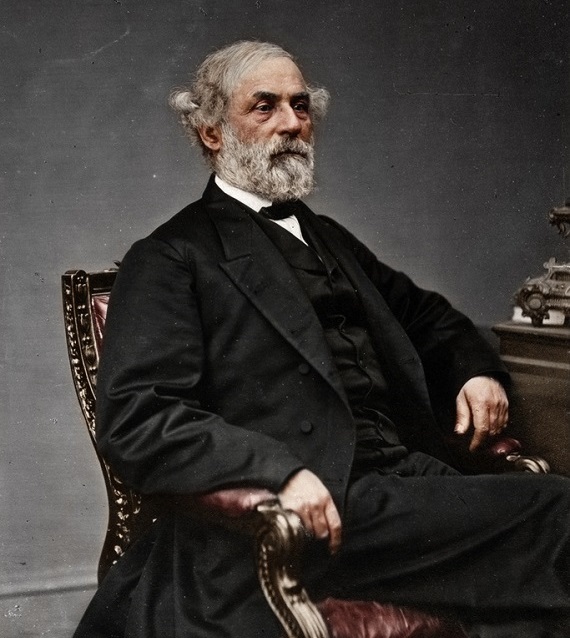

In 1866, a year after taking the surrender of the Army of Northern Virginia at Appomattox, Ulysses S. Grant had reason to consider and comment on the political landscape. At the head of what was likely the most powerful national armed force on the planet, Grant would voice an altering measure of both satisfaction and disappointment of America’s attempt to mend her scars. “Some of the rebel Generals are behaving nobly and doing all they can to induce the people to throw aside their old prejudices and to conform…Johnston and Dick Taylor, particularly, are exercising a good influence; but Lee is behaving badly. He is conducting himself very differently from what I had reason, from what he said at the time of the surrender, to suppose he would.” (1)

It is fair to observe that Grant had his own views and judgements about what ought to be taking place to restore political and social harmony in the country, the rough pace at which these events should be unfolding and the like. However, a critical reflection on the words and actions of Lee in the period from Appomattox to his death in 1870 force a reconsideration of the veracity of Grant’s statement, or at least his awareness of what was actually transpiring under the influence of his former adversary. Civil War historian Gary Gallagher has done much to establish that Lee showed immense discipline in public to avoid conflagrating the persistent tension in the land, but in private, Lee did express great anger about having lost the Civil War and over much that had unfolded as a result. (2) But while Gallagher is quite correct in noting that Lee did allow himself to express anger in private, this overall proves the General was human. It was and surely remains beyond any human being to have endured the war experiences which Lee did without some measure of afflicting anguish. Much rather is more accurate the point which Ranger Matt Atkinson, of Gettysburg National Park Service, has made that, by choosing to make active use of his immense influence towards reconciliation, Robert E. Lee time and again set a heroic and courageous example and equally committed himself to what he extolled. (3) Just a few examples suffice to challenge the views of Grant, and which have become atypical with the False Story thesis of Civil War studies.

While vacationing at the White Sulphur Springs, WV, in 1867, General Lee became troubled at the vindictiveness, ostracism and loathing that Southerners showed Northerners, particularly amongst young women of society. In his gentle but assertive manner, he went out of his way to intermingle with Northerners, asking women of such families to publicly socialise at party gatherings held each night there, with him. One night, when enquiring why none of the Southern girls who flocked about him had taken the time to greet some Pennsylvanians, he told them, ‘we are on our own soil and owe a sacred duty of hospitality.’ Pretending to fan themselves, no ladies acquiesced. Lee then rose and said, ‘I have tried in vain to find any lady…who is able to present me. I shall now introduce myself and be glad of any of you who will accompany me.’ A young Southern belle named Christiana Bond at last rose and said, ‘I will go, General Lee, under your orders.’ The Gray Fox shook his head in a fatherly manner, ‘Not under my orders; but it will gratify me deeply to have your assistance.’

As they strode across the ballroom, the General stopped beneath the chandelier to tell her of the pain he felt at the awareness of the mood of hatred, unreasoning bitterness and resentment among the South toward the North, but especially as beheld by the young people. Nearly 60 years later, Mz. Bond would recall his earnest desire for, ‘the duty of kindness, helpfulness and consideration for others.’ Bond couldn’t help but prostrate, ‘had the General never felt resentment towards the North?’ The Gray Fox told her to her etched vivid memory, he was neither bitter, nor resentful. He asked her when she returned home, ‘to take a message to your young friends.’ That being, ‘to tell them, from him, that it is unworthy of them as women, and especially as Christian women, to cherish feelings of resentment against the North.’ The General continued that, ‘it pained him inexpressibly to know such a state existed, and he implored one and all to do their duty to heal the country’s wounds.’ Lee and Mz. Bond then met with great affection the Pennsylvanians. (4)

The influence of Lee’s reconciliatory views spread throughout the resort, to no great surprise. Perhaps a rumour was started on purpose to effect a test; the young Southern ladies reported to Lee that Ulysses S. and Julia Grant were to shortly arrive as guests. What ought be the appropriate response? Lee replied, ‘If General Grant comes, I shall welcome him to my home, show him all the courtesy that is due from one gentleman to another and do everything in my power to make his stay agreeable.’ (5) Grant did not arrive, but the heroic message Lee strove for towards reconciliation was undeniable.

Challenges to Lee’s legacy, past and present, have forced a reconsideration of his image as ‘The Marble Man’, but a critical reflection of the available primary evidence and rigorous analysis by historians such as Gallagher and Atkinson leaves us with the humanity of Robert E. Lee, restored. And in testing the claims of the False Story school of historical thought of those such as Adam Serwer and Eric Foner, what is revealed in contrast is a man whose defining human trait was heroism. (6)

“It was a general belief in all the Southern states…that the example of General Lee would weigh far more in the restoration of normal conditions and true peace than any other factor in a war-torn country.” (7)

Notes:

(1) Simon, John Y., (Ed.), The Papers of Ulysses S. Grant, Vol. 16: 1866, Southern Illinois University Press, 1988, 258. Grant would add, “No man at the South is capable of exercising a tenth part of the influence for good that he is, but instead of using it, he is setting an example of forced acquiescence so grudging and pernicious in its effects as to be hardly realised…The women are particularly bitter against the Union…”

(2) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bCLPb_bUjCE [Accessed 9 January 2019]. Lee Chapel-Remembering Robert E. Lee 2009 Lecture, Gary Gallagher, “Robert E. Lee Confronts Defeat”, Washington & Lee University, Lexington, Virginia, United States, 12 October 2009.

(3) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yVFoZFH1sLM [Accessed 9 January 2019]. Gettysburg National Military Park Winter Lecture Series, Matthew Atkinson, “Robert E. Lee in the Post-War Years”, Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, United States, 3 January 2015.

(4) All above examples of Lee are to be found in Flood, Charles Bracelen, Lee: The Last Years, Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston, 1981, 161-66.

(5) Ibid, 166-67.

(6) See Serwer, Adam, ‘The Myth of the Kindly General Lee’, The Atlantic, 4 June 2017; Foner, Eric, ‘The Making and Breaking of the Legend of Robert E. Lee’, New York Times, 28 August 2017. Foner claimed in the 18 August 2017, ‘UK Telegraph‘, that Lee had never spoken out against slavery. This is disproven by the notes of William Allan held in the archives of Washington Lee University. Refer to Allan’s 10 March 1868 entry, https://www.encyclopediavirginia.org/Allan_Memoranda_of... [Accessed 9 January 2019]. See also University of North Carolina Library, Chapel Hill, MS E467.1.L4W55, ‘Genl. Robert E. Lee: An Address’, by Reverend Joseph P.B. Wilmer, 15 October 1870, 6-7, and, Life & Letters of Robert Edward Lee: Soldier & Man, The Neale Publishing Co., New York & Washington, 1906, 438.

(7) Riley, Franklin L. (Ed.), General Robert E. Lee after Appomattox, McMillian Company, New York, 1922, 132. David J. Wilson of Emmorton, Maryland, opinion cited.