Part 2 in Clyde Wilson’s series, African-American Slavery in Historical Perspective. Part 1 can be read here.

Life was tough for everyone in the America of the 1600s and 1700s. The 1800s saw some improvement which led people to entertain the idea of enlightenment and progress in living conditions. Southerners were as much conscious of and happy about a general improvement in the human condition as anyone else. As always, they were far less confident than Northerners that spiritual progress was as certain as material progress.

Nevertheless, on the eve of the War for Southern Independence, lifetime tragedy was commonplace. Poorly understood epidemics carried off significant percentages of city populations every few years. Even prosperous families were lucky to see half their children survive to adulthood. There was a terrible toll of young wives from infections associated with childbirth. Violent conflict between men was frequent and expected. A sense of fatalism and familiarity with death was perhaps what allowed soldiers in the war to risk their lives so regularly and spectacularly. And allowed Americans to commit amazing amounts of hard work through frequent sickness and debilitation while settling a continental wilderness.

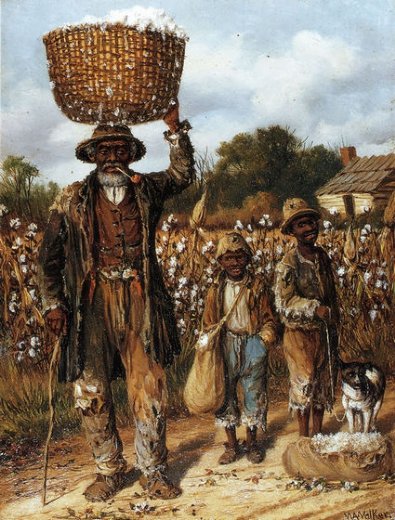

People had to plant, tend, and harvest their crops by hand, raise and slaughter their own meat, care for their own fowl, cattle, horses, and mules, make their own clothes, and often doctor and educate themselves. Not to mention the pioneer’s need to clear wooded land—backbreaking work. Anybody not fully aware of this reality is not qualified to comment on American history of the 1800s.

Possibly also, our forebears, black and white, of those times had more downtime after the work was done, and more genuine leisure for contemplation and self-entertainment than we ever-distracted moderns. The marvel of black Southern gospel music may be evidence of this.

A most significant and ignored fact of antebellum Southern society is that most slave ownings were small—5 to 10 people who lived and worked alongside white families, went to church with them, ate the same food, and were tended by the same doctors. Another large segment of owners were in the 15 to 20 slave category. On the plantation the races were closely matched in sex and generations—men and women, adults, old people, and children. This familial aspect of the slave society may indicate why many black people did not regard looting and burning by Northern invaders as a good thing.

The large planters were confined to a few areas like the Carolina rice fields, the Louisiana sugar region, and the fertile Mississippi Delta. Middling people were the backbone of the South and of the Confederacy.

Those who wish to make the true point that Confederate soldiers were not fighting for slavery often mention that only 1 in 10 soldiers owned slaves. This is a mistake. The Confederate army was full of the sons, nephews, friends, brothers-in-law of slave owners. Some Confederate soldiers hired or bought one or two black people to help their wives while they were away. About 1 in 4 of Southern families had an interest in slave property—nearly half in South Carolina, down to lower percentages in the Border States. This was a far larger percentage than Northerners who held ownership in the ruling banks and industries.

Another neglected aspect of antebellum African American history is the free black population of the South. In 1860 more than half of American free blacks were in the South. In the South many free blacks had a secure accepted place in society and were prosperous although not political citizens. It is reported that half the free blacks in Charleston were slaveowners. A section of Louisiana was occupied by free “Creoles of Colour” with large plantations. Union soldiers had not the least hesitation to rob and burn the hard-earned property of free blacks in the South.

By contrast, the black communities of the North and Canada were depressed in every social measure, exhibiting the urban dysfunction that we are all too familiar with in later times.

Another very significant aspect of the history of the Old South and slavery is that Americans were moving west in great numbers. The noted memoirist Mary Boykin Chestnut wrote an account of how her father led a long wagon train of family, slaves, and equipment from South Carolina to Mississippi, something which must have been repeated many times.

In 1860 half of the people, black and white, who had been born in Virginia, the Carolinas, Kentucky, and Tennessee were living somewhere further west or south. The Southern culture spread from the James to the Rio Grande and through the Ohio and Mississippi valleys in two centuries, covering a much greater area than Northerners. The “West” was predominantly Southern and therefor slaveholding. Southern families and their bonded people could be found at the far reaches of the Texas frontier.

According to abolitionists, Southerners were moving because they were unhappy and oppressed, or else in some conspiracy to spread slavery. But this movement was obviously a sign of a dynamic culture, with families so large it was necessary for some to move to newer lands. The problem of older, worn-out soils in the eastern states was already being solved by Southern scientists by 1860.

Technically, the slave was not the possession of the master. Though it made little practical difference, perhaps, a slave was not owned. He was bonded for his labour and had legal claims upon the master for support. Although for most of our gabbling classes Southerners are always the default villains in any scenario, in fact Southern courts were conscientious in seeking justice for bonded people when such issues came before them.

The definitive work on slavery in antebellum America, largely ignored since its appearance in 1975, is Time on the Cross by Robert W. Fogel, a Nobel Laureate, and Stanley L. Engerman. These economic historians, neither of whom can be accused of sympathy with slavery or the South, showed that in general antebellum slaves fared well in nutrition, housing, leisure—superior to the norm for the working poor in the North and Europe and were, contrary to Northern claims, more productive than Northern workers. They reported that Southern slaves received a 90% lifetime return on their labour. It is said that some Louisiana slave cabins have been converted into vacation cottages. Such residences were frequently used to hospitalise wounded soldiers.

Northerners, fond of theorizing, believed that slave labour was unproductive because they defined it as unwilling—invalidated by the simple fact of the immense productivity of staples that provided the majority of American exports. Tobacco in the 1700s and cotton in the early 1800s were the bulk of American exports. Without the South the U.S. would have had little international trade.

You have no doubt been told about how Northern visitors were shocked by the cruelly over-worked and starved slave population. There was a little of that, but most reactions were otherwise. Many visitors found the plantations peaceful and contented and Southerners admirable. Others in their letters home complained that the blacks were lazy, slovenly, and inefficient, and their masters not much better. Some could not stand the lack of puritan order and failure to focus on the bottom line. Sympathy for the enslaved was not very evident.

In his novel The Virginians, published in the late 1850s, William Makepeace Thackeray’s visitor remarks in passing that English servants worked 4 or 5 times harder than American blacks. For three centuries there has been a Northern legend that Southern people are lazy. Maybe this is in the eye of the beholder—a question of warm climate, agricultural rhythm, and a different attitude toward living, rather than a moral failing.

Plantations had no barbed wire, watchtowers, or attack dogs, or even very many locks. Slaves often slept in the same dwelling as masters. There were bloodhounds available that could track (but not attack) runaways. Corporal punishment was used on the plantation, although not as often as alleged. It was also common in the army, navy, merchant marine, factories, as punishment for crime, and in nearly every family.

But the plantation was primarily governed not by force but by moral authority, practicality, love of homeplace, and genuine affection which is evident in many antebellum and wartime Southern family letters. Fogel and Engerman also show that break up of family ties by the vast westward movement was no more common for blacks than for whites. I know of two very prominent South Carolina families who had younger sons who went West and were never heard from again.

The plantation was a place where people lived and grew crops, often over several generations. African Americans were part of a joint enterprise where all rose or fell together. Incentive rewards were normal. Work was directed by black foremen more often than by hired white overseers. A significant portion of the slave population could be classified as skilled artisans, necessary to run the self-sufficient community, of immense value to them after emancipation. African Americans commonly had their own garden plots with produce to consume or sell. Northern soldiers were shocked to find that slaves had watches and fine clothes and spending money. There were puritanical Yankee visitors who thought Southern slaves were undisciplined, rowdy, and had too much freedom.

It might be comforting to think of African Americans as violent rebels against their condition. But the real admiration should go, as Eugene Genovese showed, to the fact that the slaves used their considerable leverage to manage their condition. Of course, masters did not want their labour to run away. But where were they to go? The South was the only land in which they were welcome. The Underground Railroad has been shown to be largely a postbellum invention. Possibly more slaves were stolen and resold than successfully ran away. The novelist John Updike writes that his Pennsylvania Quaker forebears took in runaways, worked them hard, and then threw them out.

During most of the 20th century, in the reign of now-vanished nationalism, visiting Yankee tourists thought of Mount Vernon and Monticello as nice happy farms with happy people, not very different from what could be found in Ohio. Slavery was not much of an issue. John Wayne made a movie about the Alamo where all the main Southern heroes were acted by Midwesterners and a Brit and there were no Southern accents. There was even at the Alamo the New Jersey teeny-bopper idol Frankie Avalon. The same is true of the classic “The Searchers.” It is set on the Texas frontier but there is not a single Southern accent except for one buffoon.

Southern history had been absorbed, cleansed, and made into an American myth. Many doubtless thought that the Alamo was an epic of the U.S. Army. At the actual time of the Alamo, New Englanders publicly spoke of the Southern defenders of the Alamo as barbarian bandits, “lawless, renegade adventurers,” oppressors and land stealers, not as American heroes.

From the 1960s onward the idea of the Old South has reverted to a neo-abolitionist notion of the plantation as a concentration camp and a pit of evil. A parochial school student told me that the nuns teach that antebellum Southerners used their slaves for fireplace logs. American history has been made Southern again to the discomfort of nostalgic nationalists who don’t want to recognize the obvious connection between Washington and Lee, Jefferson and Calhoun. Both the Hollywood and the neo-Marxist assumptions are superficial and self-serving distortions of history for the comfort of Northerners.

Most of what passes today for the understanding of slavery has more to do with bolstering the righteousness of Northerners in their brutal invasion of the South than with the sufferings of black people in bondage.

A majority of American Presidents before Lincoln were plantation men, not to mention many others of the outstanding men who made and optimistically expanded American freedom and self-government into vast new territories. The plantation was a large and long-lasting and mostly quiet way of life, producing a leadership that has never been matched since. The U.S. is now trashing a noble part of its history. To be replaced by what?

Those who blabber about slavery these days don’t know what they are talking about. Unfortunately, those who have historical knowledge in their custody are often the worst offenders. Thus activists, “community organisers,” professors, media gurus, politicians, and government bureaucrats are now our experts on “slavery.” These are people who have always had abundant privileges, largely unearned, a free and easy life. Most have never worked up any perspiration from physical labour or wanted for anything. Their view of the world is entirely presentistic and self-centered. They lack the knowledge to conceive of other times and therefore have no right to pose as “slavery” experts. For them, the past is only a resource for extortion or virtue-signaling.

In fact, black slavery was long a fact of American society that was commonplace and seldom attacked. Some Connecticut journalists wrote a book about their surprising discovery of the link between Connecticut and slavery and white supremacy, which included violent closing of black schools and digging up black bodies from cemeteries. There should be nothing surprising about Northern racism except for the routine ignorance of Northerners about American history and their routine assumption of superior virtue.

John Randolph of Roanoke in his will freed his slaves and gave them land in Ohio, but Ohio refused to let them in. For years, R.E. Lee, in difficult economic times, worked to fulfill his father-in-law’s will to free his slaves and provide them with property. Many of those freed remained at home. In 1860 the people at Arlington were part bonded and part free. “Stonewall” Jackson established a Sunday School for black people. Jefferson Davis’s family kept close and warm ties with their slaves long after emancipation.

Contrary to what is today assumed, the Old South was not a closed and defensive society—before John Brown. Northerners and Europeans did not react in horror to their experience of slavery in the South. The division between “free States” and “slave States” was an entirely political matter and did not reflect American social life. Southern household slaves went with their masters to Northern spas, Canada, Europe, and California and generally returned home after the experience. Sometimes they traveled by themselves on family business. As in any society there were hardships for many, but for many Southerners of both races, life was easy-going.

Numerous Northerners and Europeans had no hesitation and were matter-of fact in becoming planters by purchase or marriage. Lincoln, Grant, and Stephen Douglas acquired slaves with their wives’ property and did not regard it as much more than a normal event. Lincoln had no problem in selling the slaves and as a lawyer working for the recovery of runaways.

Given that history is the sad record of the crimes, follies, and misfortunes of mankind, antebellum American bondage was an evil not near the top of the list. White and black Southerners made a livable society that had the moral resources for evolution toward a better society than that created by invasion and conquest and rivers of blood. Leading Southern clergy were already at the time of secession preaching of practical steps of progress for the black people now that the South was free to manage its own future.

Unlike Northern advanced thinkers, Southerners never denied that their slaves were made in the image of God. Unlike the leading Northern abolitionist guru Emerson, Southerners never advocated the extinction of African American people. Emerson said that the black people, deprived of the protection of slavery, would become “as rare as the Dodo.” This did not seem to trouble him in the least.

In New York City in 1860 there were women and children working 16-hour days for starvation wages, 150,000 unemployed, 40,000 homeless, 600 brothels (some with girls as young as 10), and 9,000 grog shops where the poor could temporarily drown their sorrows. Half the children in the city did not live past the age of five (unlike slave children in the South). At the same time there were ostentatiously rich men—speculators in government bonds and currency and bank and railroad stocks— who kept racehorses and mistresses, dined every day on thick steaks at Delmonico’s, lit their cigars with $50 dollar greenbacks, and when the war came enjoyed great profits and draft exemptions. No wonder that the New York city draft rioters attacked mansions of the wealthy and Republican newspapers.

Many planters had been to New York. Some had seen the slums of London. They could not be patient with the constant infamy heaped on them by malicious outsiders without a single constructive suggestion to make. They might feel some disquiet over the evils of slavery. But that encouraged them to follow St. Paul’s instruction to be good Christian masters to good Christian servants.

Real history from a real historian, as opposed to Howard Zinn, Erin Foner, that Indian neo-con, Bill Bennet, etc.

Very fine series. I’ve just read the second. I would be very interested to hear more about black slave-owners in the Ante-bellum South.