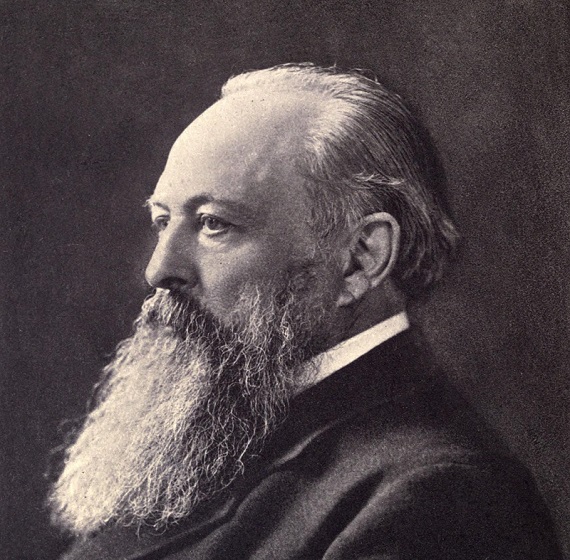

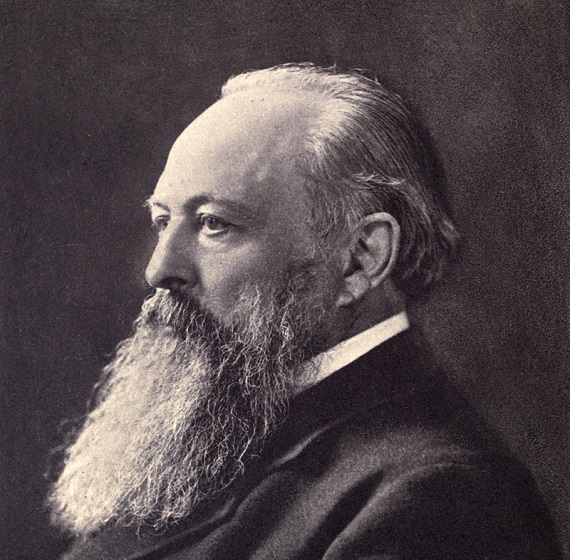

“Power tends to corrupt; absolute power corrupts absolutely.” Among Catholic students of political thought, few figures are more liable to provoke vigorous debate than does that famous dictum’s author, Cambridge history lecturer John Emerich Edward Dalberg-Acton, a.k.a., the First Lord Acton, Catholic godfather of classical liberalism. Where Acton’s critics identify classical liberalism as a theory incompatible with the Catholic faith, and point to the man’s anxieties about papal infallibility and the First Vatican Council, his supporters note that Acton explicitly sought to root his political vision in theological concepts, and was himself willing to criticize even liberals when he thought them to be getting out of hand. “[P]olitical Rights proceed directly from religious duties,” he affirmed, “and hold this to be the true basis of Liberalism.” Some might even argue that his affinity for “the securities of medieval freedom” put him a little closer than we might have at first thought to Dante and other iconic thinkers of the Middle Ages.

In any case, it is one thing to engage in serious reflection, and quite another to content ourselves with tidy tags, as if we can properly understand Acton’s endeavor merely by dropping him into a mental box labeled “liberal,” alongside everybody from Edward Abbey and Robert Penn Warren to Louis-Philippe d’Orleans and Voltaire. So rather than abstractly address Acton’s interest in liberty, it behooves us to instead examine in detail this renowned historian’s counter-cultural views regarding one of America’s defining events—the Civil War.

Whatever we may make of those views, it is worth noting from the outset that they spring from a decidedly cosmopolitan background. Born in Naples, Acton descended from an old English recusant family on one side and German vassals of the Holy Roman Emperor on the other. His transformation into a standard bearer of individual liberty came about during a youthful stint studying at the University of Munich, where his interaction with a local Catholic revival prompted him to investigate more deeply the historical basis for Anglo-Saxon political tradition. In his view, this tradition had flowered most fully and wonderfully through the independence of the former British colonies of North America.

Yet if we take for granted that Acton would be infatuated with twenty-first century Americanism we might think again, for as much as Acton thought of Jefferson and Adams, out of all American political theorists he reserved the highest praise for a man now deemed anathema: John C. Calhoun. To Acton, it was Calhoun rather than Daniel Webster who “was the real defender of the Union,” for Calhoun’s theory of nullification represented “the very perfection of political truth.” What Acton found compelling was Calhoun’s idea that in the modern age the distinctions between monarchy, aristocracy, and democracy are less significant than the distinction between centralized regimes which stifle communities and individuals, and decentralized regimes, which accord considerable agency to various quasi-sovereign actors.

Having observed Acton’s esteem for Calhoun, it is worth adding that Acton also deplored slavery, and that in the coexistence of these two seemingly incompatible sentiments we find ourselves brought up against one of the many unexamined assumptions of contemporary America. Not only is it logically possible to find slavery objectionable without regarding Southern political culture with unmitigated hostility, it is possible to oppose slavery while positively admiring Southern political culture—or at least while preferring said culture over the one which prevailed among New England Puritans.

“In almost every nation and every clime,” Acton writes frankly in his lecture “The Civil War In America,”

the time has come for the extinction of servitude. The same problem has sooner or later been forced on many governments, and all have bestowed on it their greatest legislative skill, lest in healing the evils of forced but certain labour, they should produce incurable evils of another kind. They attempted at least to moderate the effects of sudden unconditional change, to save those whom they despoiled from ruin, and those whom they liberated from destitution. But in the United States no such design seems to have presided over the work of emancipation. It has been an act of war, not of statesmanship or humanity. They have treated the slave-owner as an enemy, and have used the slave as an instrument for his destruction.

From a truly Actonian perspective, then, the militant abolitionism of the North was not the solution to slavery any more than revolutionary socialism was the solution to poverty. Thus regarding the conflict between the American North and South, the very closest Acton might have come to the conventional wisdom of twenty-first century America would have been to sternly censure both parties to the conflict: “If, then, slavery is to be the criterion which shall determine the significance of the civil war, our verdict ought, I think, to be, that by one part of the nation it was wickedly defended, and by the other as wickedly removed.”

Given his high estimation of Calhoun, however, Acton’s judgment would seem to lie even further beyond the pale of political correctness than this. While slavery may have been one of the sparks which initiated the conflagration, Acton did not deem it the pivotal issue. His interest lay not in the pace or means by which an obsolete institution was to be eliminated, but in the principle that “centralisation finds a natural barrier in the several State governments.” Would Americans recognize and correct their system’s creep toward a monolithic, unitary nation-state by emphasizing constitutional limits upon the central government’s authority? Or would the American project degenerate into a “consolidated” mass democracy, which is to say one whereby a few select mandarins unrestrained by legal limitations dictate life to unseen, unknown subjects far and wide? That was the question. Where Northerners had been seduced by utopian promises of consolidation, among Southerners “the very defect of their social system preserved them from those political errors which were transforming the original characters of the Northern Republics.”

In a warm and respectful postwar letter to Robert E. Lee, Acton frankly admitted where his own sympathies had been all along:

I saw in State Rights the only availing check upon the absolutism of the sovereign will, and secession filled me with hope, not as the destruction but as the redemption of Democracy. The institutions of your Republic have not exercised on the old world the salutary and liberating influence which ought to have belonged to them, by reason of those defects and abuses of principle which the Confederate Constitution was expressly and wisely calculated to remedy. I believed that the example of that great Reform would have blessed all the races of mankind by establishing true freedom purged of the native dangers and disorders of Republics. Therefore I deemed that you were fighting the battles of our liberty, our progress, and our civilization.

Only those aware of the visceral associations the apocalyptic Napoleonic Wars must have had for an Englishman can appreciate the full force of Acton’s astonishing confession to Lee: “I mourn for the stake which was lost at Richmond more deeply than I rejoice over that which was saved at Waterloo.”

Returning to Acton’s essay about the Civil War and its aftermath, we find even more astonishing, darker remarks:

The spurious liberty of the United States is twice cursed, for it deceives those whom it attracts and those whom it repels. By exhibiting the spectacle of a people claiming to be free but whose love of freedom means hatred of inequality, jealousy of limitations to power, and reliance on the State as an instrument to mould as well as to control society, it calls on its admirers to hate aristocracy and teaches its adversaries to fear the people. The North has used the doctrines of Democracy to destroy self-government.

Today we necessarily pause over such predictions, for there is no denying America’s ever-increasing “reliance on the State as an instrument to mould as well as to control society.” Academic conformity and tech censorship, along with migrant mania and transgender bathroom wars suggest that unconditional egalitarianism is indeed the order of the day, just as the case can be made that dogmatic hatred of aristocracy has given us both a disingenuous, hypocritical elite and a vulgar, uniform culture purged of chivalry, class, and magnanimity.

Whatever the case, the bare fact stands: Acton believed that the wrong side won the American Civil War, and his judgment was shared by many prominent English Catholics. Such a judgment could hardly be said to be a minor detail of someone’s historical worldview, yet this judgment has somehow been obscured. I can peruse treatments and invocations of Acton on numerous outlets without finding even a hint of his claim that postbellum America’s “spurious liberty” would be “twice cursed.” For my part, I am neither a classical liberal, nor an adherent of the Whig theory of history, nor do I entirely concur with the claim that power is per se corrupting. For all that, I am still perfectly willing to give a respectful hearing to such a formidable scholar’s opinion about America’s nineteenth-century transformation. In so doing, maybe I am more open and attentive to Acton than some who would claim to follow in his footsteps.

This piece was originally published in Crisis Magazine.