He yaf nat of that text a pulled hen

That seith that hunters ben nat hooly men

It was recently found, in the skeletal remains of Egyptian tombs, that scribes of the Pharaonic era suffered from maladies to the joints of the shoulder, neck, and knees. A unique posture, held for hours, contorted these men and shaped their very bones to the point an archeologist today can decipher just how they sat. Comparing images drawn from the ancient period with the injuries discovered, they are consistent with what is depicted — scriveners sitting in cross-legged or one-legged squatting positions. A higher incidence of osteoarthritis was found in the joints along the right side, likely meaning this was the side they leant on. Even the jaws and teeth showed signs of the trade. From excessive chewing on the reeds used to write, these pencil nibblers damaged their temporomandibular joints. This is contested, as the Egyptian diet was one of hard vegetables and bread which often had mixed in coarse sand or small rocks. Yet still, among the scribes, this injury was found twice as often.

Time and its depredations has not yet concealed what these men did in their lives. There is no escaping their occupation — even the sedentary bear scars. Millenia have come and gone, but the mundanity still lives.

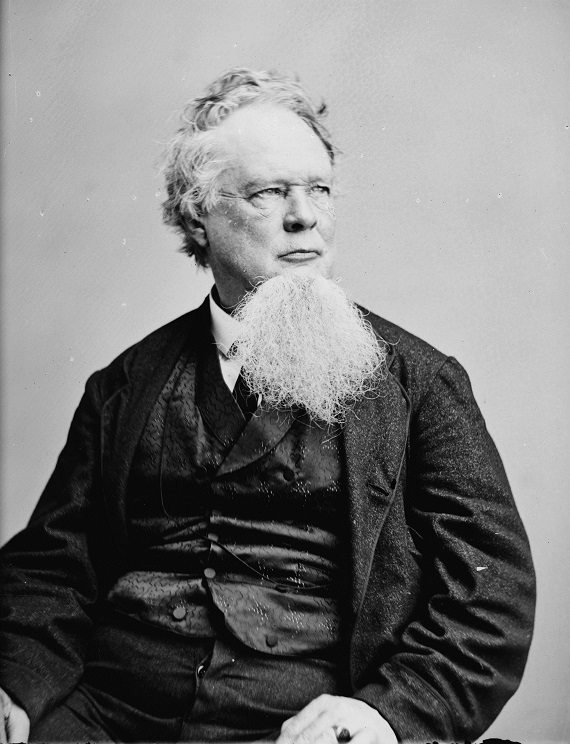

Reading Theodore Rosengarten’s introduction to the University of South Carolina Press’s edition of William Elliott’s Carolina Sports by Land and Water may give you the impression Elliott’s mortal remains resting in Magnolia Cemetery resemble these arthritic scribblers of Egypt. You may wonder how Elliott, born in 1788 in Beaufort, South Carolina into immense wealth, who during his life served his state as a representative and senator while also being an avid sportsman, could possibly be characterized as he is by the introduction: irresponsible, lazy and pampered — therefore his radial joints are likely intact and undisturbed, having never strained in any endeavor, for all was provided unto him. You may wonder, as you approach the end of the essay, why did anyone bother to publish what Elliott had to say? You will be dissuaded, ultimately, from taking up the rest. You will put the book on the shelf where it will sit for months, then years, then finally given away at an estate sale. There will be a single bend in the spine, right where the introduction ends. No other page will be touched. There will be no evidence of it having been read entire. And thus, the introduction to the 1994 edition served its ostensible purpose.

Aside from the glaring errors and a few odd inferences, the essay preceding Carolina Sports rarely addresses whether the book possesses literary merit. It takes the form of a personal grudge towards the man who wrote it, informed by the rummaging through of Elliott’s letters, finding faults common to all men throughout history. Let us examine the Sports through a more literary lens — a more appropriate eye when introducing a work that has yet to be out of print since 1846.

Elliott Pursued

The same year Carolina Sports was published, William Gilmore Simms provided his thoughts in a lengthy essay in The Southern Quarterly Review. Simms mostly praised the book; he closes his review with “the hope that he will not permit them to be the only fruits of his leisure imparted to the public.” However, Simms, the towering figure of his age, in a most genial way did offer critique. To our loss and indignation, these mild correctives are highlighted by Mr. Rosengarten as proof that Sports is not a book of any merit. Simms is press-ganged from the grave and used as an unwilling critic — his positive opinion is conspicuously absent. And yet, even these friendly suggestions made by Simms seem off the mark.

There can be no doubt Elliott’s Sports is written in a style one may deem kinetic. The stories seethe and roll, charge on, dash into tangles, and can seem incoherent taken as a whole. Simms notes an inaccuracy in language when Elliott writes in “Devil Fishing:”

After all there is no sport, the world over, like the fisherman’s. What of your horse-racing, theatre gazing, or tripping it down of a hot summer’s night to the clatter of noteless pianos, split clarionets, cold iron triangles and crazy tambourines? No! give me a tight boat, clean tackle, a few jolly friends, and a warm pleasant sky, and adieu ladies and gentlemen, to your dry land pastimes, as you have no zest for what is far richer, I assure you, if they are more dearly bought. Pardon me if I can’t dance to your piping — the fashion of the thing is gone — the soul that once animated it is dead — and is to have for us no resurrection.

Simms charges Elliott with an “over-excited vivacity” that diminishes the sport: When compared to out-of-tune instruments, would not any pleasure, however small, be more enjoyable? There are a few ways to consider this. Simms possibly could not understand the effect Elliott tries to convey. Charleston’s premier man of letters, Simms much preferred the comradery of the hunting camp over the pursuit itself. It is not a stretch to infer from the passage Elliott writes that all falls into dissonance, even the most serene, when compared to the ceremony that is the hunting of devil-fish. It is but one effect on the reader, following Elliott’s prose glide along the chop, impelled by a force not seen but known deep within a void. In the tumult, in the seaborne joust, there is a greater harmony than music, at least to Elliott; and he, with only language as his device, attempts to make it known within the limitations set.

Read with care, it can be understood the hunt, with its own signs and instruments — the harpoon, the fathoms of rope, the knots, the pulling of the oars, the creak of the bow, and all men working together towards the singular goal — possesses a higher unity. Elliott stands as conductor, as primus inter pares, among his crew and sons as he dashes lance after lance some dozen yards away into leviathan. If this does not suffice, if what is written still seems a reach, it should be noted Elliott was a frequent guest at opera houses, here and in Europe, and thus not unfamiliar with music.

It is at times a fair charge made by Simms — Elliott himself admits in the Sports to writing with abundance. Yet Simms founders when, with a full head of steam, he declares “Few readers relish riding through the woods at headlong speed in a book any more than on horseback.” De gustibus non est disputandum, but if the writer of hunting stories were to omit the chase, the stalk, the eyes leveling on the quarry, then all he’d produce would be an instruction manual.

Rosengarten makes mention of Simms’s note that Elliott’s style “is deficient … in the art which conceals art.” His introduction attempts, when analyzing the chapter “A Business Day at Chee-ha,” to say Elliott was indeed capable of concealing his art. However, the conclusions strain credulity, and do not remotely approach what is written — whether this happened through malice or ignorance, no one can say. Herein Elliott tells the story of visiting one of his plantations. At the beginning, he is tempted to take part in a hunt by a hunting companion. It is a near-perfect autumn day — Creation lures him to drive his horse and hounds into the wood. “Business before pleasure,” says Elliott — but beneath he yearns to break free of his obligations. From here, Elliott notes in fine detail his trip down the road passing through his property. As a learned agrarian, Elliott notes better drainage is needed — an observation ignored or missed by Rosengarten, who casts him as an absentee planter.

Elliott dismounts and enters his barnyard where he is greeted by innumerable demands from the enslaved. Cloth and shoes, everyday necessities that Elliott must attend to or else leave those in his charge wanting. This episode, as described by James Everett Kibler in The Mississippi Quarterly, is the demonstration of noblesse oblige. What makes Elliott crack is not the excess of wants nor the hostile atmosphere among the slaves, as Rosengarten crudely infers, but when he is addressed as old, though only 45 years of age. Elliott, during his visit to Chee-ha, was two years younger than the age when his father passed away.

He sets off at this, in mind and body, hoping to evade his mortality in the hunt. But even here his limits are revealed. He ponders on a scene near the Ashepoo:

the dark waters … glided noiselessly by, flinging here and there a bubble to the surface, which broke or disappeared to give place to other bubbles; and as the leaves, fanned by a gentle southern air, fell rustling from the surrounding trees to mingle with and be lost in the earth that received them, I mused, and bethought me that they were but too apt emblems of human fortunes, and human life! Where were the original lords of this soil, whose dark forms glided, in by-gone days, through these forests; intent, like ourselves, on the pleasures of the chase? Gone like those bubbles! scattered like the leaves of a former season by the blast of the whirlwind, or buried (as those now falling about me were soon to be) undistinguished beneath the soil! their musical dialect every day upon our tongues, and they — forgotten as though they had never been! And where were they who dispossessed them? The early white colonists? — gone like themselves! The spreading oaks hard by, marked their traditionary graves; but their histories, their very names, already indistinct from time …

His finitude, amid all his boasts and his vaunting, is there before him in a bubble and a leaf. After this revery a deer he kills lands in the river and the current takes it further out. He is told by his younger companion to stay ashore, much to his frustration. Elliott witnesses the younger man undress and knows what stands before him is one with better days still ahead, one not weighed down with the intricacies of maintaining multiple plantations. Life is consumed by minor yet necessary details, all at the expense of grand ventures.

One last irritates the sensibilities from the latest edition’s introduction. Rosengarten calls Elliott’s use of classical allusion, Greek, and Latin “archaic” and “pompous”; that they read “like a conscious attempt to sound old, English, well-read.” Perhaps, it is forgotten, but in that time, especially in the South, it was customary to study Latin and Greek before university and to have read what we once called a decade or two ago the Western canon. These expressions would not be a mystery to his audience, and even the introduction acknowledges — when it suits the purpose — that the writer of Carolina Sports wrote for his contemporaries. Perhaps these allusions seem pompous to the insecure, to the dispossessed, to the one steeped in popular culture, but Elliott’s use of the ancients and their tongues is not arrogance. More often it is clever, as in the extended Latin paragraph found in “Devil Fishing.” There may be a solecism in Elliott’s use of Milton, but it does not detract from the overall worth.

It must be understood that Elliott attempts in Carolina Sports to fuse multiple literary traditions into his high velocity tales, those being folklore, hunting instruction, and philosophy. There are evocations of Xenophon and Plato in the Sports: from the former’s treatise On Hunting and his approval of the sport as it keeps men from growing old; the latter, in The Laws, expressing favor towards the sport as a way to instill virtue, and to teach men the lay of the land, knowledge valuable on multiple planes. If there is any overly conscious attempt on Elliott’s behalf in his use of what we now consider dead languages, it is to demonstrate that hunting and fishing are ancient practices, ones venerated throughout the ages, in any land. For the reader, it has the effect of conferring authority, and bestows an eternal aspect on the thoughts written, that they are not produced ex nihilo. The stories Elliott tells are not simple didactic tales of fish escaping hooks and therefore we must have patience. For us, Elliott extends Xenophon to our time and our shores by continuing the work he began. In Elliott’s case, it may have been subconsciously performed — a habit of who he and his people were. His use of the ancients and various literary devices only compounds the import by tethering himself to the skiff of the masters.

As time elapses, Carolina Sports emerges not as an anti-abolitionist screed, but as an exhortation of the art of hunting and a re-enchantment of the Lowcountry. The half-dozen sentences of antiquated scientific justifications for slavery do not create more than a ripple compared to the splash and rollicking of the rest. They do not interfere with the renditions of ubi sunt, of the Dantean flourishes bemoaning the state of Beaufort as a city beyond its golden age. To assign, as the unfortunate introduction does, all meaning of the Sports based off a letter and those few lines is to confuse the forest for the trees. There need be no apologia for the peculiar institution to appreciate the book–let there be none. It is near impossible to read his lamentation of General Pinckney’s estate, submerged into the realm of the devil-fish Elliott hunts, as overwrought and fit for a time defined by ersatz chivalry. The rich descriptions of landscape, the topographical erudition, none of these are impaired. The Sports today serves as a cultural artifact beyond portions of the author’s intent.

Elliott and Historical Myth

What of the Sports today? It is a richly detailed, exciting story — the sprinting prose, the parables festooned in the flora of our region. It is a literary work of merit — there is a reason it remains in print to our time, the only American sporting book to do so, more than a century and three quarters later. But why re-examine a work observed previously?

A new edition is necessary, an edition that understands the value of the work. For reasons, many and various, a re-introduction of the Sports is necessary for the people who have come to settle the Lowcountry in droves, and for those who have lived here for generations who want the native son to be given his due.

Carolina Sports is one of few works describing this area and the men who once inhabited it. With so few, our eye is drawn to Elliott, and we are by some ascriptive nature obliged to find reason enough to bring him to the fore again. With the internal migration of many thousands, a republication of Elliott is a chance to welcome these many, to show them what once was, and to impart a sense of how the people lived then and still do in some ways today — for example, the driven deer hunt remains active in parts of the Lowcountry.

More importantly, the Sports teaches the virtue of hunting and fishing; it is in line with the old precepts, all needed during any age. When Rosengarten dismisses Elliott and his brotherhood of hunters as a “half-baked form” of democracy, he throws away thousands of years of once understood knowledge: It is by ceremony, through the hunt, that the limitations of man against nature are revealed in earnest, and only by knowing them can we form a body politic fit for self-rule. The hunt is immune to the slogan, to the chant, to the hollow verbiage prattled on and on. It was Simms, when reviewing Elliott, who said a nation’s sports are oftentimes more important than their laws.

Elliott is a vestige of something even older than the antebellum South. He inhabits for us what Allen Tate called Historical Myth — specifically, the toga virilis. This myth is a curious feature found only in the West — to see ourselves “in the stern light of the character of Cato.” It is lower myth than religion but was common after the Renaissance with so much study of the Greeks and Romans. This propensity creates legends that order life. It is largely gone today, seen only in fragments as we walk in the older parts of town. By returning Elliott to his rightful place as a writer to be read and held in regard, we can begin again to write our own literature, a Southern literature, one informed by a vast heritage. We have the architecture, now let us bring back the poetry denied to us.

Carolina Sports is a book to be read in adolescence for its verve and thrill. Later, to be enjoyed again, but this time for its art. Further on, for its meditations on life. It is a book ripe at any age. We cannot let it sink into obscurity and disrepute.

“What unthought-of-page, in the unsearchable book of futurity, might yet be ours!” Elliott perorates along the shore of the Ashepoo. Let his page be one as author, as a cherished writer who gives voice to tales from the ACE Basin down to the waters near Beaufort. Let the page of the book of today call him what he is: a reveling practitioner of the timeless arts of hunting and fishing here in our region.

This essay was originally published at the Charleston Mercury.