Editor’s Note: This selection is from William Gilmore Simms’s The Life of Francis Marion and is published in honor of his 217 birthday, April 17.

Marion’s career as a partisan, in the thickets and swamps of Carolina, is abundantly distinguished by the picturesque ; but it was while he held his camp at Snow’s Island, that it received its highest colors of romance. In this snug and impenetrable fortress, he reminds us very much of the ancient feudal baron of France and Germany, who, perched on castled eminence, looked down with the complacency of an eagle from his eyrie, and marked all below him for his own. The resemblance is good in all respects but one. The plea and justification of Marion are complete. His warfare was legitimate. He was no mountain robber,—no selfish and reckless ruler, thirsting for spoil and delighting inhumanly in blood. The love of liberty, the defence of country, the protection of the feeble, the maintenance of humanity and all its dearest interests, against its tyrant these were the noble incentives which strengthened him in his stronghold, made it terrible in the eyes of his enemy, and sacred in those of his countrymen. Here he lay, grimly watching for the proper time and opportunity when to sally forth and strike. His position, so far as it sheltered him from his enemies, and gave him facilities for their overthrow, was wonderfully like that of the knightly robber of the Middle Ages. True, his camp was without its castle but it had its fosse and keep—its draw-bridge and portcullis. There were no towers frowning in stone and iron but there were tall pillars of pine and cypress, from the waving tops of which the warders looked out, and gave warning of the foe or the victim. No cannon thundered from his walls; no knights, shining in armor, sallied forth to the tourney. He was fond of none of the mere pomps of war. He held no revels—”drank no wine through the helmet barred,” and, quite unlike the baronial ruffian of the Middle Ages, was strangely indifferent to the feasts of gluttony and swilled insolence. He found no joy in the pleasures of the table. Art had done little to increase the comforts or the securities of his fortress. It was one, complete to his hands, from those of nature—such an one as must have delighted the generous English outlaw of Sherwood forest; insulated by deep ravines and rivers, a dense forest of mighty trees, and interminable undergrowth. The vine and briar guarded his passes. The laurel and the shrub, the vine and sweet scented jessamine, roofed his dwelling, and clambered up between his closed eyelids and the stars. Obstructions, scarcely penetrable by any foe, crowded the pathways to his tent ;—and no footstep, not practised in the secret, and to the manner born,’ might pass unchallenged to his midnight rest. The swamp was his moat; his bulwarks were the deep ravines, which, watched by sleepless rifles, were quite as impregnable as the castles on the Rhine. Here, in the possession of his fortress, the partisan slept secure. In the defence of such a place, in the employment of such material as he had to use, Marion, stands out alone in our written history, as the great master of that sort of strategy, which renders the untaught militiaman in his native thickets, a match for the best drilled veteran of Europe. Marion seemed to possess an intuitive knowledge of his men and material, by which, without effort, he was led to the most judicious modes for their exercise. He beheld, at a glance, the evils or advantages of a position. By a nice adaptation of his resources to his situation, he promptly supplied its deficiencies and repaired its defects. Till this was done, he did not sleep;—he relaxed in none of his endeavors. By patient toil, by keenest vigilance, by a genius peculiarly his own, he reconciled those inequalities of fortune or circumstance, under which ordinary men sit down in despair. Surrounded by superior foes, he showed no solicitude on this account. If his position was good, their superiority gave him little concern. He soon contrived to lessen it, by cutting off their advanced parties, their scouts or foragers, and striking at their detachments in detail. It was on their own ground, in their immediate presence, nay, in the very midst of them, that he frequently made himself a home. Better live upon foes than upon friends, was his maxim; and this practice of living amongst foes was the great school by which his people were taught vigilance.

The adroitness and address of Marion’s captainship were never more fully displayed than when he kept Snow’s Island; sallying forth, as occasion offered, to harass the superior foe, to cut off his convoys, or to break up, before they could well embody, the gathering and undisciplined Tories. His movements were marked by equal promptitude and wariness. He suffered no risks from a neglect of proper precaution. His habits of circumspection and resolve ran together in happy unison. His plans, carefully considered beforehand, were always timed with the happiest reference to the condition and feelings of his men. To prepare that condition, and to train those feelings, were the chief employment of his repose. He knew his game, and how it should be played, before a step was taken or a weapon drawn. When he himself, or any of his parties, left the island, upon an expedition, they advanced along no beaten paths. They made them as they went. He had the Indian faculty in perfection, of gathering his course from the sun, from the stars, from the bark and the tops of trees, and such other natural guides, as the woodman acquires only through long and watchful experience. Many of the trails, thus opened by him, upon these expeditions, are now the ordinary avenues of the country. On starting, he almost invariably struck into the woods, and seeking the heads of the larger water courses, crossed them at their first and small beginnings. He destroyed the bridges where he could. He preferred fords. The former not only facilitated the progress of less fearless enemies, but apprised them of his own approach. If speed was essential, a more direct, but not less cautious route was pursued. The stream was crossed sometimes where it was deepest. On such occasions the party swam their horses, Marion himself leading the way, though he himself was unable to swim. He rode a famous horse called Ball, which he had taken from a loyalist captain of that name. This animal was a sorrel, of high, generous blood, and took the water as if born to it. The horses of the brigade soon learned to follow him as naturally as their riders followed his master. There was no waiting for pontoons and boats. Had there been there would have been no surprises.

The secrecy with which Marion conducted his expeditions was, perhaps, one of the causes of their frequent success. He entrusted his schemes to nobody, not even his most confidential officers. He consulted with them respectfully, heard them patiently, weighed their suggestions, and silently approached his conclusions. They knew his determinations only from his actions. He left no track behind him, if it were possible to avoid it. He was often vainly hunted after by his own detachments. He was more apt at finding them than they him. His scouts were taught a peculiar and shrill whistle, which, at night, could be heard at a most astonishing distance….

His expeditions were frequently long, and his men, hurrying forth without due preparation, not unfrequently suffered much privation from want of food. To guard against this danger, it was their habit to watch his cook. If they saw him unusually busied in preparing supplies of the rude, portable food, which it was Marion’s custom to carry on such occasions, they knew what was before them, and provided themselves accordingly. In no other way could they arrive at their general’s intentions. His favorite time for moving was with the setting sun, and then it was known that the march would continue all night. Before striking any sudden blow, he has been known to march sixty or seventy miles, taking no other food in twenty four hours, than a meal of cold potatoes and a draught of cold water. The latter might have been repeated. This was truly a Spartan process for acquiring vigor. Its results were a degree of patient hardihood, as well in officers as men, to which few soldiers in any periods have attained. These marches were made in all seasons. His men were badly clothed in homespun, a light wear which afforded little warmth. They slept in the open air, and frequently without a blanket. Their ordinary food consisted of sweet potatoes, garnished, on fortunate occasions, with lean beef. Salt was only to be had when they succeeded in the capture of an enemy’s commissariat; and even when this most necessary of all human condiments was obtained, the unselfish nature of Marion made him indifferent to its He distributed it on such occasions, in quantities not exceeding a bushel, to each Whig family; and by this patriarchal care, still farther endeared himself to the affection of his followers.

The effect of this mode of progress was soon felt by the people of the partisan. They quickly sought to emulate the virtues which they admired. They became expert in the arts which he practised so successfully. The constant employment which he gave them, the nature of his exactions, taught activity, vigilance, coolness and audacity. His first requisition, from his subordinates, was good information. His scouts were always his best men. They were generally good horsemen, and first rate shots. His cavalry were, in fact, so many mounted gunmen, not uniformly weaponed, but carrying the rifle, the carbine, or an ordinary fowling-piece, as they happened to possess or procure them. Their swords, unless taken from the enemy, were made out of mill saws, roughly manufactured by a forest blacksmith. His scouts were out in all directions, and at all hours. They did the double duty of patrol and spies. They hovered about the posts of the enemy, crouching in the thicket, or darting along the plain, picking up prisoners, and information, and spoils together. They cut off stragglers, encountered patrols of the foe, and arrested his supplies on the way to the garrison. Sometimes the single scout, buried in the thick tops of the tree, looked down upon the march of his legions, or hung perched over the hostile encampment till it slept, then slipping down, stole through the silent host, carrying off a drowsy sentinel, or a favorite charger, upon which the daring spy flourished conspicuous among his less fortunate companions. The boldness of these adventurers was sometimes wonderful almost beyond belief. It was the strict result of that confidence in their woodman skill, which the practice of their leader, and his invariable success, naturally taught them to entertain.

The mutual confidence which thus grew up between our partisan and his men, made the business of war, in spite of its peculiar difficulties and privations, a pleasant one. As they had no doubts of their leader’s ability to conduct them to victory, he had no apprehension, but, when brought to a meeting with the enemy, that they would secure it. His mode of battle was a simple one; generally very direct; but he was wonderfully prompt in availing himself of the exigencies of the affair. His rule was to know his enemy, how posted and in what strength, then, if his men were set on, they had nothing to do but to fight. They knew that he had so placed them that valor was the only requisite. A swamp, right or left, or in his rear; a thicket beside him ;—any spot in which time could be gained, and an inexperienced militia rallied, long enough to become reconciled to the unaccustomed sights and sounds of war, were all that he required, in order to secure a fit position for fighting in. He found no difficulty in making good soldiers of them. It caused him no surprise, and we may add no great concern, that his raw militia men, armed with rifle and ducking gun, should retire before the pushing bayonets of a regular soldiery. He considered it mere butchery to expose them to this trial. But he taught his men to retire slowly, to take post behind the first tree or thicket, reload, and try the effect of a second fire; and so on, of a third and fourth, retiring still, but never forgetting to take advantage of every shelter that offered itself. He expected them to fly, but not too far to be useful. We shall see the effect of this training at Eutaw, where the militia in the advance delivered seventeen fires, before they yielded to the press of the enemy. But, says Johnson, with equal truth and terseness, “that distrust of their own immediate commanders which militia are too apt to be affected with, never produced an emotion where Marion and Pickens commanded.” The history of American warfare shows conclusively that, under the right leaders, the American militia are as cool in moments of danger as the best drilled soldiery in the universe. But they have been a thousand times disgraced by imbecile and vainglorious pretenders.

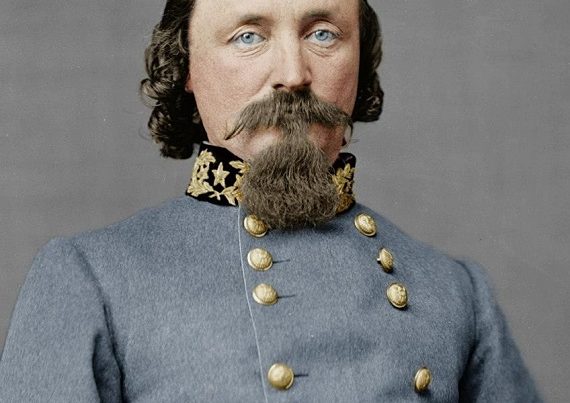

In his writings about his own partisan command, Col. John Singleton Mosby mentions Marion as being a boyhood hero but he also makes plain that his own particular method of partisan/guerrilla warfare was considerably more dangerous for himself and his men than was Marion’s. First, Marion had his “swamp” as well as his place of safety as written about in the above article. Mosby noted that he was in open country and although his men could take to the woods, there was no place of absolute safety. Whether they were separated (as they were most of the time or together in one of those bands used to attack the enemy, there were no really “safe places.” One of his Rangers wrote of falling asleep by the wall in a cemetery only to hear a large Yankee contingent passing along on the road just outside of that wall!

I did not realize I shared a birthday with William Gilmore Simms. It was the Abbeville Institute webinar on Simms and the Marion biography that brought me to South Carolina for my birthday. Truly, we’ve come full circle.