“If you, who represent the stronger portion, cannot agree to settle [the issues] on the broad principle of justice and duty, say so; and let the States we both represent agree to separate and part in peace. If you are unwilling we should part in peace, tell us so, and we shall know what to do, when you reduce the question to submission or resistance.” John C. Calhoun, from his speech read in the Senate Chamber by James Murray Mason of Virginia on March 4, 1850

Maryland’s curious honor roll of distaff Unionists includes Clara Barton from North Oxford, Massachusetts and two Pennsylvanians, an apocryphal flag waver named Barbara Fritchie and the singularly unremarkable Matilda Sterling, who complained that the citizens of Annapolis and Baltimore were secessionist and “very bitter in their feelings” towards Federal occupation troops. Their objectives by necessity subordinated to the overarching imperative to write a more palatable “Civil War” history, feminist ideologues glorify these transplants as exemplars of “strong, right-thinking Maryland” women “ahead of their times,” while they typically neglect the Old Line State’s more numerous, home-grown Confederate heroines.

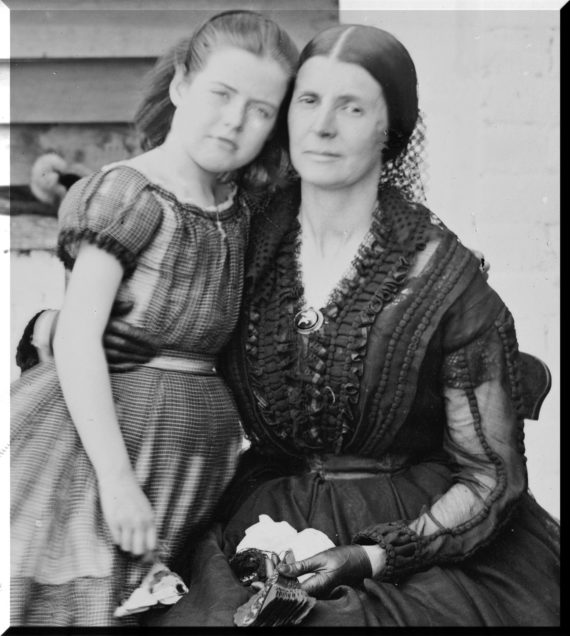

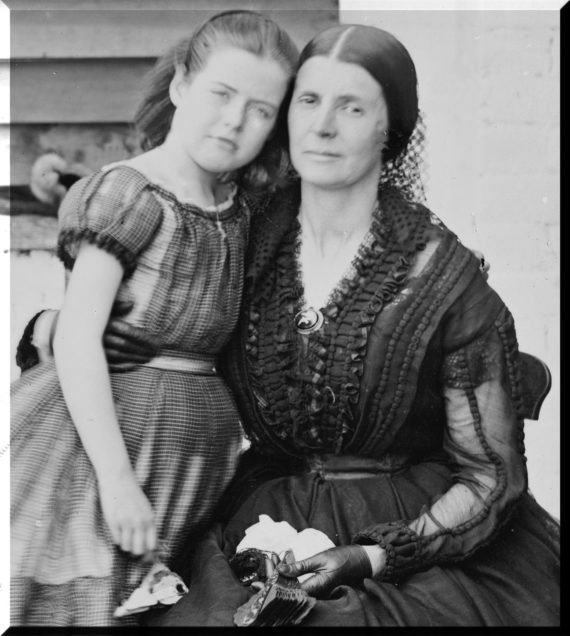

But the most dedicated votaries of the abstraction that is the coequality of the sexes have discovered that the mannish deeds of Rose O’Neal Greenhow serve their purposes too well to ignore her, forgiving her “infamy” or at least understanding it as an unfortunate inevitability. Just as Raphael Semmes and Franklin Buchanan, Greenhow is re-contextualized by “correct” historians as a Yankee sympathetic to the Confederacy out of a venal self-interest, a turncoat debased by the “alien” politics of the “benighted” lower region of the country. She was the product, they explain, of the culturally aberrant slave-holding planter class of an otherwise respectably “Northern” state and a casualty of the accident that was her association with John C. Calhoun. Greenhow, in spite of elaborate interpretations of the past or what reconstructionists would prefer, was not an errant Northerner; she was a Southerner proud that “no drop of Yankee blood ever polluted [her] veins” and grateful to Calhoun that her “first crude ideas on state and federal matters” had “received consistency and shape” from him.

Assuming the mantle of the long-reigning Dolly Madison, Rose, politically astute and influential to the point of provoking rival factions, presided over antebellum Washington society, and, even during the onset of the war, D.C. elites still coveted invitations to her candlelight suppers, opportunities for Rose to extract information from Yankee officials tipsy from Madeira and charmed by her honeyed tone of voice. A key operative in Colonel Thomas Jordan’s spy ring, organized before he left the Union army, she educated herself on battlefield tactics and ordinance, producing sophisticated and detailed reports on defenses and troop movements which, when discovered by them, astounded the Union’s military men. George McClellan admitted that Rose knew his plans “better than Lincoln or the Cabinet” and that she had “four times compelled [McClelland] to change” those plans.

Rose and her husband, Robert, who died in 1854, were life-long friends of Calhoun. When Congress was in session, he was their frequent guest, though more often a roomer at the Capitol Hill boarding house owned by Rose’s aunt. This was the building in which Congress had convened in the days following the torching of Washington by the British in 1814. It was also where the teenaged Rose O’Neal, newly arrived from Montgomery County, Maryland, was introduced to the philosophy of the senator from South Carolina and where he would “breathe his last.” During the struggle between North and South, the boarding house would become part of the Radical Republicans’ Old Capitol Prison complex, the room in which the dying Calhoun, with Rose in attendance, had shared with her his “prophetic wisdom” functioning as the search area for new prisoners, including Rose herself.

Her covert career marked by what she insisted was only an apparent counterintuitive recklessness, she seemed to invite the attentions of the Lincoln government, a regime she considered an “inquisitorial hierarchy.” Benjamin Butler harbored a murderous rage towards the “haughty dame,” and he once hinted at torture when he expressed a desire to “put her through an ordeal” at Fortress Monroe, a Union prison in Virginia. Allan Pinkerton, however, was more temperate in his feelings towards Greenhow allowing that she had “uncommon social powers” while regretting that she had employed them in “wicked” insurrectionism and had “robbed” good men of their “patriotic hearts.”

By August of 1861, the novelty of the beautiful spy having worn thin, the Northerners finally placed Rose under house arrest, but at “Greenhow Prison” in Northwest D.C., a contingent of eighteen guards watching her night and day could not stop her intrigues. Permitted outings in the company of a military escort, Rose, on one of those promenades, tossed a ball of pink wool containing a coded message into the window of a Confederate courier, calling out “Here is the yarn you left at my house.” The message reached President Davis a few days later. At the request of Davis, she stopped using cipher and resorted to correspondence that appeared to concern itself with trivialities which puzzled the Yankees who respected her for her keen mind if not for her treachery. In one letter, she requested that an Aunt Sally be informed that she had “some old shoes for the children,” the “old shoes” being intelligence Greenhow wished to convey to Richmond.

Transferred to Old Capitol in January of 1862, Rose, in spite of agents provocateur, maintained regular contact with the Davis government. After only a few months, a now haggard and thin Rose, a shawl concealing the Battle Flag she had wrapped around her shoulders, walked out of that prison to begin an “exile” to the Confederacy, Belle Boyd arriving at Old Capitol shortly after Rose’s departure. In choosing to engage in spying for the South, Greenhow forfeited an elevated social position and the prospect of living out the war in Washington with its levees and Friday-night theater-going; acquiescence to the Radicals would have brought with it approbation and ease; instead, resistance had led to humiliation and hunger in Yankee captivity.

Not only vilified by Northerners, who questioned her virtue and her sanity, she was thought by many in Richmond to have conducted counterespionage on behalf of U.S. Secretary of State Seward. But the Richmond Dispatch lauded Rose as a “true Southern lady” who had frustrated the designs of “the tyrant,” Abraham Lincoln. And Mary Chestnut, in A Diary from Dixie, writes that her husband, James Chestnut, aide to Davis, said of Greenhow, that the South owed her “a debt it [could] never pay” because she had “warned [the Confederates] at Manassas” and they had summoned Joe Johnston and “his Paladins,” a decisive win ensuing for the South, a revelatory and crushing blow for the Yankees.

President Davis himself immediately called on Rose and instructed the treasury to disburse $2500 to her for her service to the South. An ally of Davis and Judah P. Benjamin, she had hardly settled in when she was caught up in politics, defending Davis against his foes, most prominent among them Alexander H. Stephens and Robert Toombs, both of whom were connected with the Richmond Examiner, a newspaper that accused Varina Davis of “aping royalty.”

Rose’s visit to the capital coincided with the “battles before Richmond,” and she was saddened by the suffering that had purchased Confederate victories in those engagements while she showed no pity for the Union casualties, the Union dead, about whom she coldly commented: “The scene of their insolent triumph was changed into a charnel-house, with the very air rank…with the effluvia from their half-decomposed bodies.” (Phoebe Yates Pember, a Low Country aristocrat of Jewish descent, who was a matron at Chimborazo Hospital in Richmond during the war, in her memoirs notes with tongue in cheek that “Christ had died in vain” for the South’s Christians because of their hatred for the Yankee).

Though Richmond, like Washington D.C., was cursed with its share of the societal ill that was the ascendancy of “mudsills” to use Greenhow’s word, it was not the desperate city that it would be by war’s end when the upper classes would be dancing at starvation balls and the “bottom rail on top” would be reveling in mischief of every sort. In pre-Pennsylvania campaign Richmond, there were picnics and evening festivities that had an air of normalcy. But secure within the Davis government’s inner sanctum, Rose mainly busied herself with stitching Battle Flags and knitting socks and gloves for the soldiers.

A month after the Battle of Gettysburg, she said goodbye to Richmond and sailed for Europe where she presented herself to the crowned heads as an emissary for the South and published a book which William Saffire described as “florid and self-serving,” not an entirely baseless criticism given Rose’s inclination towards the histrionic. But she indulged in the inflated rhetoric not atypical of her era, and she played no minor role in the Southern cause, though North-friendly post-1960s history is always careful to qualify her accomplishments and to caution that too much praise for Rose is clearly Neo-Confederate romanticism.

Tragically, this self-styled Marie Antoinette, was never to step foot on Southern soil again. In 1864, returning to America, she was aboard the Scottish-built blockader the Condor, when the vessel foundered on the New Inlet Bar off of Cape Fear. The rowboat carrying her to safety capsizing just offshore from Fort Fisher, she drowned never having sworn allegiance to the Republican government because she was “of a section of the country” that “makes an oath binding.”

Had she been on the “right side,” Rose would be as celebrated as Fritchie, and Whittier would have immortalized her in verse. Elementary schools long ago having removed Greenhow biographies from their library shelves, teachers still faithfully treat Fritchie’s fictitious defiance of General Jackson as proof of Maryland’s nationalistic fervor. But if feminists insist ad nauseam, as they do, on the glorification of female trailblazers, if the truth about the North’s war on the South is acknowledged, they will find considerably more of them among those whose flag was not the one that legend says Barbara Fritchie unfurled at Jackson on the eve of the Battle of Sharpsburg.

Olivia Floyd was a principal in the Confederate government’s negotiation of the release of the St. Albans “raiders” held by Canadian authorities in a Montreal jail. Born in Baltimore, Floyd by the 1860s was living at Rose Hill in Port Tobacco, Maryland. Her resentment of the Federal soldiers encamped on the grounds of Rose Hill had reached a fever pitch when, from her front gate, she repeatedly fired a pistol at the Yankees. They retaliated by burning fences on the property. The incident seemingly forgotten, the Floyds extended hospitality to the soldiers, inviting some of them to stay in the house, the former home of Gustavus Brown, one of the physicians who ministered to George Washington in his final moments at Mount Vernon. But everyone retired for the night, Olivia, carrying dispatches, would sneak out and ride to Pope’s Creek, Maryland, the site of a Confederate signal corps station, hurrying back home before dawn.

Routine but indifferent searches of the Rose Hill mansion yielded nothing of interest, the Yankees failing to find $80,000 hidden inside the stuffing of a hassock and a communiqué from Canada requesting that the Confederates send proof that Lieutenant Bennett Young and his detail had acted under military orders when they robbed banks in St. Alban’s, Vermont in the fall of 1864. Olivia had placed the dispatch in the brass andirons on which the soldiers, their halfhearted efforts concluded, had propped their muddy boots. When they left, with that paper pinned up in her hair, she once again rode to Pope’s Creek. For her efforts on behalf of the Confederacy, she received laurels from Jefferson Davis. And at the age of 75, she was honored and serenaded at the 1900 Confederate veterans reunion in Louisville, Kentucky, an event she attended at the request of Young.

Southern partisanship was not the exception in Maryland and not peculiar to the sound on the eastern bank of the Chesapeake Bay, and women all over the state assumed the patriotic duty of aiding the South. Most engaged in simple acts of charity, often anonymous. A correspondent for the Charleston Mercury, Felix G. De Fontaine, reported that an unidentified woman in Frederick distributed money and tobacco to Southern soldiers and, with fourteen other ladies, made clothing for them. But she confided to De Fontaine that she did not display Southern flags in her windows because she feared reprisals from the Northern occupiers once General Lee and his troops moved on.

Under abolitionist rule small kindnesses could be risky: Virginians and Marylanders (and the strongly secessionist indigenous population of Washington, D.C.) were arrested for an offhand comment, a gesture or an “offensive” facial expression. New Englander Benjamin Butler, who never commanded men in battle, was the leader of the occupation forces in Baltimore where he arrested women for seditionist singing, brandishing the Battle Flag and wearing red (or black as they did when they learned that Jackson had died at Guinea Station, Virginia). Hetty Cary was sent to Fort McHenry for appearing in public in a white pinafore trimmed in red ribbon, but she received no punishment for “flaunting” a Battle Flag she and her sister Jennie had designed and sewn because a Union colonel said that Hetty was pretty enough “to do as she (expletive deleted) please[d]!” Members of Baltimore’s Monument Street Girls, Hetty and Jennie adapted the words of James Ryder Randall’s “Maryland! My Maryland!” to the tune of an old German folk song and insulted the Yankees by singing the anthem that was to be the South’s Marseilles.

Like Clara Barton, Euphemia Goldsborough, was a nurse, but unlike Barton, she was a blooded Marylander. At the commencement of hostilities in 1861, her family’s home became a refuge for Confederate soldiers and a clearing house for blockade runners delivering and dropping off mail and contraband. In the aftermath of Sharpsburg, Euphemia and several women from Baltimore traveled to Frederick to care for the Southern wounded. Her next post was the newly established POW camp at Point Lookout in occupied St. Mary’s County.

As Southern fortunes declined, Euphemia crossed the Mason Dixon to care for the Confederates captured at Gettysburg. When the hemorrhaging Waller Tazewell Patton, great-uncle of General George Patton, was unable to breathe unless in an upright position, there being no alternative, Euphemia with her back to his, sat up all night supporting the unconscious man, who, nevertheless, died the next morning. Remaining with the POWs when they were relocated to a hospital at the Union’s Camp Letterman, Euphemia, however, following the unexpected death of one young Texan, left straightaway for Baltimore. From there she wrote a letter of condolence to the family of her former patient Sam Watson and continued her underground work until arrested and sent southward. It was not until after the war that she would return to Baltimore, where she would raise funds for Southern relief. Although Euphemia, while at Camp Letterman, treated the Union wounded as compassionately as the Confederate, she was there to help her own people, and she despised the Northern abolitionists.

For sheltering a Southern soldier and for possession of Confederate mail, Marylander Elizabeth Waring Duckett and members of her family were not exiled but imprisoned at Old Capitol. The Warings were involved in the underground postal service, as were John Surratt Sr. and John Surratt Jr., the husband and son of Mary Surratt. A Post Office was located at the Surratt Tavern in Southern Maryland, and the two men would mix mail bound for the Confederacy with the U.S. mail they handled. When Duckett and the Warings were being transported to D.C., their coach stopped at the tavern and “the gracious old lady Mrs. Surratt,” brought mint juleps out to them.

Occupation troops concerning themselves as much with juvenile demonstrations as with the more “egregious” acts of “subversion” committed by the Warings and their fellow insurgents, they sent sixteen-year-old Sallie Jarvis, of the Eastern Shore, to Old Capitol for making a three-by-six-inch Battle Flag to fly over a chicken coop some little boys “playing soldier” had made their army fort. In her memoirs, Jarvis’s prison mate Virginia Lomax, who was from the Old Dominion, mocks the Northerners:

“Men were…dispatched to undertake the hazardous task of reducing the fortress, and capturing…the entire garrison and its colors….A prisoner…was brought before General Baker, and liberty promised if he would give the name of the person who presented the colors. In case of refusal, the orderly had ready a…weapon of birch…to inflict condign punishment on the obdurate little rebel….with many tears and cries, the ungallant soldier confessed….”

Jarvis and Lomax were shortly joined by those accused of conspiring to assassinate Lincoln. Mrs. Surratt favorably impressing Lomax, the younger prisoner in her writings juxtaposes the widow’s refinement and compassionate disposition with the bloodlust of the feral mobs—mainly the opportunistic-turned-retributionist demimonde drawn to wartime Washington—surrounding the prison night and day demanding Surratt’s death. Detained briefly in Old Capitol, Surratt petitioned Lomax to pray for her as she was leaving for the Old Arsenal Penitentiary, where she would be kept initially in a cell measuring no more than three by eight feet and where she would be tried by the Yankees. The charges against Surratt were not revealed to her until she made her first appearance in a hastily whitewashed courtroom filled with wind-borne mosquitoes and the demoralizing reek of the cess in nearby St. James Creek.

Mary Surratt’s complicity in the assassination, her witting or unwitting participation in the Southern underground, the latter having no bearing on her guilt or innocence regarding with the former, are subjects for conjecture, though it is unlikely that she was unaware that her son John Surratt was well-known to the Davis administration and knee-deep in Confederate subterfuge. Visited on a number of occasions by John Surratt’s friend the preternaturally good-looking and manipulative John Wilkes Booth, his last appearance there the morning of the assassination, the Surratt residence, now a Chinese restaurant called the Wok and Roll, was a safehouse for blockade runners, spies and couriers, among them people involved in the St. Albans affair and the three young men who accompanied Mary to the gallows: George Atzerodt, a German immigrant, pharmacology student David Herold, from Maryland, and Floridian Lewis Powell (Payne), who, on July 7, 1 865, standing at the scaffold, declared her innocent and himself in league with Booth and culpable in the assassination plottings.

The special pleading, witness tampering and the pervasive irregularities that marked the prelude to a lynching that was Surratt’s “trial,” are of no consequence because her court martial itself was an extraconstitutionality not justified, Special Judge Advocate John A. Bingham’s arguments to the contrary notwithstanding, by the Congressional Act of March 3, 1863 which required that anyone guilty of aiding and comforting traitors stand before a military tribunal. This bizarre non sequitur is an example of the inherently unlawful expediencies often devised by the 16th president and the Radical Republicans who carried on in his tradition. The same raw Federal power that had spawned the secession crisis had in a real sense murdered Mary Surratt, her “crimes” her regional identity and “treasonous” boarding house clientele.

Early on, some of the citizens of Maryland and the rest of the Borderland South, had vainly sought to remain neutral, an impossibility in the face of the North’s perfidy and its precipitous reduction of their region to a reviled and conquered appendage to Northern territory, but they were soon to realize the high stakes of the war and what a Confederate defeat would mean. Because she had been schooled by Calhoun, Rose Greenhow appreciated the malign irony of Salmon P. Chase’s assurance to her that the North was waging its war to “rescue” America from a “ruthless despotism,” and she feared the enormity that would be a Northern victory and the imposition of what William Tecumseh Sherman with chilling blandness called the “nation’s will.” In her memoirs, Greenhow records Calhoun’s deathbed prediction that the United States would “prove a failure,” that “an irresponsible majority would override [the] conservative element.” The North, chaffing under the proscriptions of the Constitution, “at no distant day,” Calhoun warned, would “set aside the constitutional restraints…and eventually bring about a revolution.”

A century and a half ago, when those Northern revolutionaries descended on them, Southerners were compelled to defend their homeland’s sovereignty. Today the coerced “weaker portion” is no less obligated to resist tyranny through the penultimate measures of interposition and nullification, and, those failing, to resort to dissolution, a Providentially-bestowed remedy irrevocable by the passage of time or by historical positivism to ideological ends.