As the old cliché goes, “One man’s terrorist is another man’s freedom fighter.” The phrase has been around forever, it seems, and sometimes it can be true, I suppose. There are always exceptions to every rule. But most of the time, a terrorist is simply a terrorist, a person who uses extreme violence and fear to achieve a political or social objective. And make no mistake, Nat Turner, who led a bloody slave revolt in Virginia in 1831, was a terrorist.

As the old cliché goes, “One man’s terrorist is another man’s freedom fighter.” The phrase has been around forever, it seems, and sometimes it can be true, I suppose. There are always exceptions to every rule. But most of the time, a terrorist is simply a terrorist, a person who uses extreme violence and fear to achieve a political or social objective. And make no mistake, Nat Turner, who led a bloody slave revolt in Virginia in 1831, was a terrorist.

To this irrefutable fact Turner freely admitted without hesitation in an interview with attorney Thomas R. Gray, who was allowed into Turner’s jail cell after his capture. In Gray’s work, The Confessions of Nat Turner, published soon after Turner’s execution, the accused rebel confessed that “my object [was] to carry terror and devastation wherever we went” and to “strike terror to the inhabitants.”

As Gray wrote of the cold, calculating fanatic before him, “The calm, deliberate composure with which he spoke of his late deed and intentions, the expression of his fiend-like face when excited by enthusiasm, still bearing the stains of the blood of helpless innocence about him; clothed with rags and covered with chains; yet daring to raise his manacled hands to heaven, with a spirit soaring above the attributes of man; I looked on him and my blood curdled in my veins.”

After Turner’s admission of his terrorist objective, Gray then asked him, “Do you not find yourself mistaken now?” Turner answered without emotion, “Was not Christ crucified?” Likening himself to Christ, this was where Turner drew is inspiration: The Bible and his belief in a twisted version of Christianity, an Old Testament “eye for an eye, tooth for a tooth” mentality that is certainly nothing like the lessons taught by Christ, who taught His true disciples to “love one another as I have loved you.” (John 13:34-35)

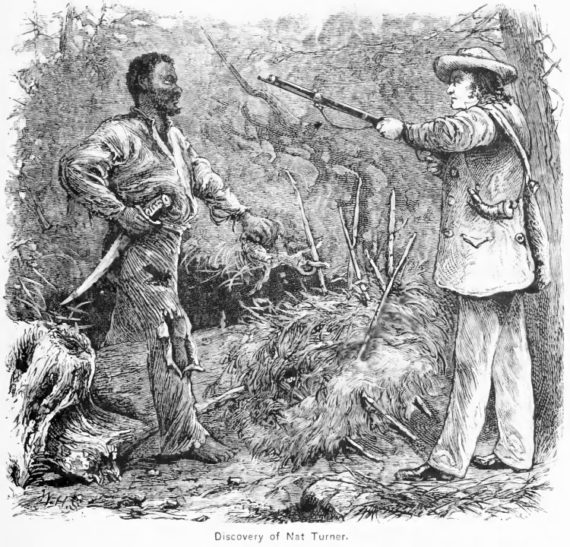

Nat Turner’s horrific violence took place in August 1831 in Southampton County, Virginia. Turner was a slave and preacher on a small plantation who believed he “was ordained for some great purpose in the hands of the Almighty.” That purpose, he soon contended, was to lead a slave revolt to overthrow the institution that had enslaved so many of Africa’s children.

As he told Gray, he “heard a loud noise in the heavens, and the Spirit instantly appeared to me and said the Serpent was loosened, and Christ had laid down the yoke he had borne for the sins of men, and that I should take it on and fight against the Serpent, for the time was fast approaching when the first should be last and the last should be first.” So Turner saw himself as one taking up Christ’s mantle, what is known in Christian theology as a “false Christ” – an “Anti-Christ.”

After the appearance of confirming “signs in the heavens,” which were two solar eclipses in February and August 1831, Turner set out to end slavery by brutally killing every white person he and his followers could find, the same objective John Brown would have 28 years later. Fear and terror would spread, the movement would grow, and slavery would eventually end through terroristic violence. In the end, he and his men slaughtered as many as 60 whites, most of them women and children, before the reign of terror ended at the hands of the militia and armed citizens.

Today, in our present climate of political correctness and extreme partisan sensitiveness, scholars are working to give Nat Turner his due, while historical archeologists are searching for the final resting places of Turner and his gang, who were all buried in unmarked graves after their execution. Their purpose is to honor them for what they fought for – their freedom. The city of Richmond, Virginia recently got in on the act by announcing that Nat Turner will be featured on a new emancipation statue soon to be erected in the capital city, even as a statue of Robert E. Lee is targeted for removal.

Turner’s newfound fame began in earnest after Nate Parker’s feature film, “The Birth of a Nation,” hit theaters nationwide in the fall of 2016. Around the same time, National Geographic produced a documentary, “Rise Up: The Legacy of Nat Turner,” hosted by Robert G. Smith, one of the actors in Parker’s film.

As for the Parker movie, “The Birth of a Nation,” many critics, including historians, have been downright brutal in their assessment of it. And rightfully so. After sitting through two hours of agony, there’s not much positive that can be said. As for what the film got right, well, there was a slave revolt in Southampton County, Virginia in 1831 led by a slave-preacher named Nat Turner that took the lives of 60 whites. Aside from a few minor issues where the movie succeeded, there’s little that can be said by way of praise.

What the film got wrong? Most everything else. The film’s writers took the worst stereotypes, the most gruesome depictions one could envision about the Old South (and probably of every other place on Earth at the time) and made it seem as if the entire region was an armed concentration camp led by the cruelest of men. In one particularly grisly scene, one slave owner, using an iron hammer and chisel, knocked out every tooth of a rebellious slave, and then brutally force-fed him with a metal funnel.

The movie made the rape and brutalization of slave property seem a common, everyday occurrence. Parker’s slave catchers rape, kill (one horrific scene depicts the body of a dead slave with his brains literally blown out laying beside the road for all to see), and threaten slaves even above the protest of some masters. It was as if the slaves did not really belong to anyone as chattel but to the white community as a whole.

White men – any white man – seemed to have free reign to do as they pleased. Parker turned all white men in the South into uncontrollable, sex-crazed, murderous thugs (another scene, during the uprising, showed a white overseer getting out of bed with a very young black girl who couldn’t have been more than 10 or 12 years old). It was as sickening as it was infuriating, for the film was made to seem as though no good white men existed in the Old South.

In one major historical flaw, Nate Parker’s “Nat Turner” was not so much inspired by religious fanaticism, if not outright mental illness, as he was motivated by a desire to exact revenge for what was happening to him and to other slaves in Southampton County.

His wife, Cherry Turner (a relationship in historical dispute, as was any children, for the film depicted Turner with a daughter), was brutally beaten and gang-raped by a slave patrol. Her face was pounded so bad that she was unrecognizable, not even resembling a human being. Turner’s friend, and soon-to-be fellow rebel, suffered a similar, albeit less physically violent, incident with his wife, as the master and his friends sought companionship after an evening dinner party.

Although one writer for Slate.com believed there was “some evidence” for the attack on Turner’s wife and at least one other slave on the plantation, Professor Leslie Alexander of Ohio State, who called the film “an epic fail,” wrote that there is “not a shred of historical evidence to suggest that Cherry [Turner] was ever raped by slave patrollers, nor is there any evidence to indicate that an attack on his wife inspired Turner to rebel. By all accounts, Turner took up arms against slavery because he believed slavery was morally wrong and violated the law of God.”

In short, this film, “The Birth of a Nation,” was revolting and downright nauseating, meant more to turn popular opinion as anything else. As one writer stated, Parker’s “rage jumps off the screen.” And that’s what Parker meant to do, to use an emotional hook to twist history to suit a political agenda. It would, to borrow from Paul C. Graham, further the current state of “Confederaphobia.” But Parker likely failed in his effort.

Vinson Cunningham, an African-American writing in The New Yorker, wrote that the film “is not worth the efforts of its defenders. It’s hard even to call it a successful attempt at propaganda.” And even Parker admitted in an interview with “60 Minutes” that the film “is not 100 percent historically accurate.”

A self-described “black journalist” who reviewed the movie for CNN called it “a historical injustice” that took “too many creative liberties with Nat Turner’s history.” He also had real problems with Turner’s marriage, the child he had in the film but probably not in real life, and the rape allegation.

The film also portrayed the end of the revolt as a heroic stand against the militia at the armory in Jerusalem, Virginia, the objective of Turner and his men, in which ole Nat manages to somehow escape to the swamp to hide out. In reality, they never reached the armory, although Turner did manage to elude capture for two months. He was later hanged for his crimes. After the hanging scene, Parker transitions it into a battle scene with black troops in the War Between the States, thereby linking Turner’s revolt to the end of slavery and to the “birth of a nation,” something that has been on the lips of many Nat Turner defenders in recent years – the importance of his revolt to the end of slavery in America, although it was three decades prior to secession and war.

The National Geographic documentary, if it could be worse, was just that, if only for a different reason – an attempt to turn Nat Turner into a political martyr. The film was not so much a historical documentary as it was a political statement.

“Rise Up: The Legacy of Nat Turner,” hosted by Robert G. Smith, who played the slave “Isaac” in “The Birth of a Nation” and considers Turner “an American revolutionary” even though “he has never been embraced as such,” is an attempt to humanize and “hero-ize” Nat Turner. In every interview in the film, there is an outpouring of sympathy for Nat Turner and not a single dissenting voice throughout the hour-long narrative.

The first two interviews set the mood. “Birth of a Nation” writer/producer/director/actor Nate Parker, who played Nat Turner in his film, says, “People remember Nat Turner as a fanatical killer, rather than a freedom fighter driven by faith.” Professor of history Sarah Roth, of Widener University, contended, “Black people who stand up for themselves, especially if they use violence against whites to do it, are never considered heroes in America.” And it went downhill from there, very far downhill.

In one of the earliest exchanges, Smith interviews a Turner descendent named Bruce Turner, who owns a cotton farm in the same area as the Turner revolt. As he agonizes over the “back breaking work” of picking cotton every day, as if no whites ever had to do it, he reminds us of the slaves’ rough “existence in this cotton field. You got somebody standing over you. You got somebody telling you your life will end if you don’t pick this cotton. Because the choice between being a slave and not being a slave was death.” It was as though the slaves had no real value at all. But I’m sure the slave’s owner would have had a lot to say about such a policy.

The documentary is broken down into several parts, examining a different aspect of Nat Turner’s “legacy.” In the first part, entitled “A Legacy of Education,” the film examines the fact that Turner could read and write very well, something that some seek to stress to young African-American kids today. In this section, the interviewee is Nadia Lopez, a principal at an academy in Brooklyn, New York who has made it her mission to emphasis education to young blacks, particularly her reading program. She says, “My work is a representation of Nat Turner. He was willing to lay down his life and he was willing to be the example of saying ‘we deserve better.’”

As she was speaking, and the film was depicting scenes from around Brooklyn, the camera centered on a single flyer glued to a light pole. Decrying the recent murder of some black youths, it read in part, “This community will no longer tolerate this violence. Do not shoot anyone. Do not stab anyone. …” One wonders if the irony was lost on any of the filmmakers.

In the second section, “The Legacy to Never Forget,” the filmmakers interview a black farmer, as he worked in his fields. He says, “I think people in a hundred years will see Nat Turner as more of a patriot. He was trying to make sure these people got free.” Narrator Smith then describes how Turner and his men moved from farm to farm killing “all whites – men, women, and children, all slave owners – on the bloody road to freedom.”

If it seems as though the film is defending Turner’s actions, that’s because it is, most decidedly so. In an interview with an African-American consultant, Brian Flavor, who holds two master’s degrees, he says of Turner’s brutality against white women and children, “Well you raped women and children. You subjugated women and children and never allowed them to be adults and we are still with those remnants today.” Aside from the fact that neither he nor anyone else in the film ever provides any hard evidence of their allegations, women and children were subjugated around the world at the time, not just blacks in the Old South.

Section Three, “A Legacy of Oppression,” opens with an interview with a young black man in Brooklyn who claims he has been stopped over 100 times by the police since he was 13 years old. So you can see where this is continuing to lead. The young man, named Darian, found out he was born on the day Nat Turner was executed, igniting an interest in the slave rebel. “Nat for me represents a fire that kind of like sparked in all of us to be free.”

The fourth section, “A Legacy of Rising Above,” features a historical archeologist, Dr. Kelly Fanto Deetz, who is searching for all things Nat Turner – namely the execution spot and his burial plot. She wants a memorial in Southampton County (since there are none) to honor Turner. She likens him and “his rebels” to Confederate soldiers, who “also fought for their freedom.” The fact that Southern troops did not slaughter women and children seems to have escaped her rationale.

Use ground-penetrating radar devices, Deetz and her team seem to have located the spot where Turner was hanged. The tree no longer stands but one radar operator believes he knows where it stood, from the underground images. Says an emotional Deetz, “It’s crazy to me that there was a tree that was fairly large right here that enslaved people literally died on.” And if whites had committed a similar crime, they too would have swung from the same tree. Smith, getting a bit emotional, kneels down, picks up some grass, and gently rolls it in his hands, as if he is on hallowed ground.

But the crème de la crème was the discovery of, or what is at least what is purported to be, the final resting place of Turner and his gang after their execution. They were all buried in the same area with no markers. Today it’s a grown up thicket with bit of trash lying around and a rural road dissecting it. Deetz decries the dishonor of such a fate. “To me this speaks volumes that there’s a trash pit over here, with a road running through it, with complete disregard for black lives and not having a place for people to come pay homage to Nat Turner.” Both Smith and Deetz are emotionally elated as radar operators discover what is later determined to be human bone fragments. Unbelievably as it sounds, Smith likens the area to Plymouth Rock and Ellis Island.

And finally the last section, called “A Legacy of Rebellion,” features the 3rd great-grandson of Frederick Douglass, who, like Smith, likens Turner to some of America’s greatest heroes. “Revolutionaries like Nat Turner should be a part of the freedom narrative of this country just like the Founding Fathers were.” For Deetz, Nat Turner deserves a monument. “We have Confederate monuments all over the South so why can’t someone like Nat Turner have similar monuments, just like the fallen soldiers of all of our wars? These rebels are fallen soldiers of their own cause and their own battle.” Smith calls for memorializing Turner as an “American freedom fighter.”

It’s difficult to believe such thinking exists today, particularly in our age of terrorism. How can we honor a man, in any meaningful way, whose revolt deliberately took the lives of women and children, of whom at least seventeen were under the age of ten? If he had only attacked and killed white male slave owners, perhaps he could gain some legitimate sympathy, and perhaps things would be different. But he didn’t. He killed without mercy and without distinction, as all terrorists do.

Making things much worse, he likened himself to Jesus Christ, all because of religious fanaticism and a misguided belief in Christianity, not any cruel treatment by his master. In fact, as he said to Gray in the Confessions, “Since the commencement of 1830, I had been living with Mr. Joseph Travis, who was to me a kind master, and placed the greatest confidence in me.” But, unfortunately, that didn’t save Mr. Travis or his family from being brutally murdered.

Consider these selections from Gray’s Confessions. They are nothing short of horrific:

I must spill the first blood. On which, armed with a hatchet, and accompanied by Will, I entered my master’s chamber, it being dark, I could not give a death blow, the hatchet glanced from his head, he sprang from the bed and called his wife, it was his last word, Will laid him dead, with a blow of his axe, and Mrs. Travis shared the same fate, as she lay in bed. The murder of this family, five in number, was the work of a moment, not one of them awoke; there was a little infant sleeping in a cradle, that was forgotten, until we had left the house and gone some distance, when Henry and Will returned and killed it.

…

We entered and found Mrs. Turner and Mrs. Newsome in the middle of a room, almost frightened to death. Will immediately killed Mrs. Turner, with one blow of his axe. I took Mrs. Newsome by the hand, and with the sword I had when I was apprehended, I struck her several blows over the head, but not being able to kill her, as the sword was dull. Will turning around and discovering it, despatched [sic] her also. A general destruction of property and search for money and ammunition, always succeeded the murders.

…

As I came round to the door I saw Will pulling Mrs. Whitehead out of the house, and at the step he nearly severed her head from her body, with his broad axe. Miss Margaret, when I discovered her, had concealed herself in the corner, formed by the projection of the cellar cap from the house; on my approach she fled, but was soon overtaken, and after repeated blows with a sword, I killed her by a blow on the head, with a fence rail.

…

Having murdered Mrs. Waller and ten children, we started for Mr. William Williams’ – having killed him and two little boys that were there; while engaged in this, Mrs. Williams fled and got some distance from the house, but she was pursued, overtaken, and compelled to get up behind one of the company, who brought her back, and after showing her the mangled body of her lifeless husband, she was told to get down and lay by his side, where she was shot dead. I then started for Mr. Jacob Williams, where the family were murdered.

Such acts are the work of madmen. Nat Turner obviously suffered from insanity, at least to some degree. Hearing voices and seeing apocalyptic visions is not the behavior of sane, rational people, in our day or his. Despite the misguided musings of his worshippers, Nat Turner was no hero. He was a bloodthirsty murderer who was justifiably hanged for his awful crimes. He’s deserving of no monument, memorial, or honor of any kind. To pay homage to Nat Turner would be akin to honoring the 9/11 hijackers at the World Trade Center. May Turner always be remembered for what he really was: a terrorist.

Sources

National Geographic, “Rise Up: The Legacy of Nat Turner,” http://www.nationalgeographic.com.au/tv/rise-up-the-legacy-of-nat-turner/.

Thomas R. Gray, The Confessions of Nat Turner: http://docsouth.unc.edu/neh/turner/turner.html.

Rasha Ali, “Historian Calls Nate Parker’s ‘Birth of a Nation’ an ‘Epic Fail,’” TheWrap.com: http://www.thewrap.com/historian-calls-nate-parkers-birth-of-a-nation-an-epic-fail/.

Clay Cane, “‘Birth of a Nation’: A Historical Injustice (Opinion),” CNN.com: http://www.cnn.com/2016/10/07/opinions/birth-of-nation-review-cane/index.html.

Vinson Cunningham, “‘The Birth of a Nation’ Isn’t Worth Defending,” The New Yorker: https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2016/10/10/the-birth-of-a-nation-isnt-worth-defending

Rebecca Onion, “How The Birth of a Nation Uses Fact and Fiction,” Slate.com: http://www.slate.com/blogs/browbeat/2016/10/14/the_birth_of_a_nation_historical_accuracy_what_s_fact_and_what_s_fiction.html.