A review of None Shall Look Back (J.S. Sanders, 1992) by Caroline Gordon

Thus far the War Between the States has failed to produce an epic like The Iliad, a narrative account of the four-year conflict that would include the exploits of all the heroes of both sides. In fact, few Southern novelists have written fictional accounts of Confederate warriors— possibly because not enough time has elapsed, possibly because there are many good histories and biographies that perform the chief function of the epic—to help a people remember their heroic past.

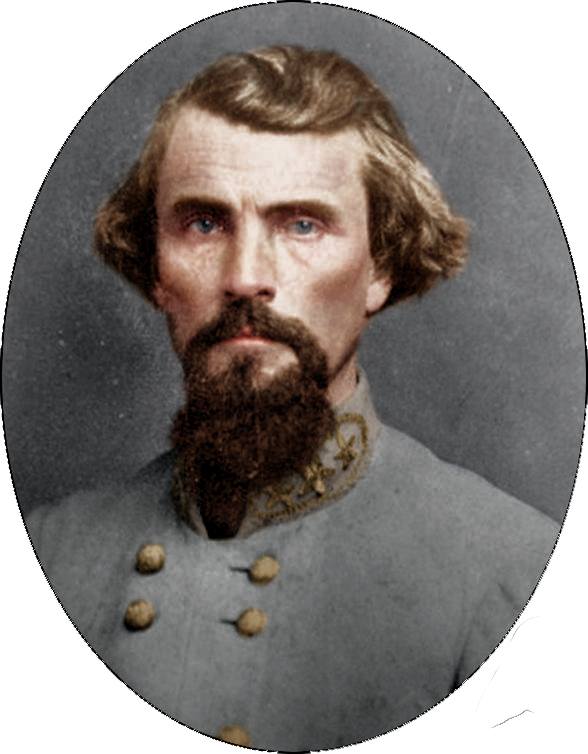

However, a few genuine literary talents have attempted to create epic portraits of Confederate heroes, and one of the best of these is Caroline Gordon, a novelist whose literary works are only now, after a half century, beginning to win the attention they’ve always deserved. Her portrayal of Nathan Bedford Forrest in None Shall Look Back, recently reissued by J.S. Sanders, Inc., should be read by every student of Confederate history, not merely because it accurately portrays the ebb and flow of battle, but also because it defines the crucial role of the military hero in a time when a nation and its people are in jeopardy.

Gordon’s rendition of Forrest — like Andrew Lytle’s in his history Bedford Forrest and His Critter Company — is one of admiration unmitigated by reservation or irony. A Southern woman of her generation, Gordon did not explore the politically incorrect side of Forrest, who not only owned slaves but was also in the business of buying and selling them. Instead, she gives her readers the pure image of the natural soldier, the larger-than-life leader who inspires his men to fight bravely and, if need be, to sacrifice their lives in defense of their country.

In order to show this heroic figure in action, Gordon tells the story of the Allard family, and particularly of the two Allard men—Fontaine I and Rives—who pursue opposite L courses in response to the War, Fontaine’s out of weakness, Rives’ out of strength. Fontaine stays at home, manages the plantation, and in so doing attempts to keep the family intact. Rives chooses to fight the enemy and ends up serving as a spy for Nathan Bedford Forrest.

As soon as Rives encounters his commander, he realizes he has found a figure larger than life. At this stage of the War, Forrest is still a colonel, but he already winning a reputation as an officer who exposes himself to great danger in the process of leading his troops and as a consequence wins unlikely victories against superior odds. Here is what Allard sees early in the narrative:

Forrest’s horse had been shot out from under him. A shell crashing through the horse’s body just behind the rider’s leg had tom the already wounded animal to pieces. The rider, disentangling himself, went forward on foot. He was splashed with blood and his overcoat had fifteen bullets in it, but he was uninjured. Placing his hand on one of the bloody gun carriages he threw back his head and yelled with triumph. His men yelling too gave him back his own name: “Forrest! Forrest!” Then still hysterical with joy they ran about over the field, gathering up the (weapons} of the enemy’s dead and wounded.

Thus Forrest is portrayed as an inspirational figure, a hero whose conduct in battle transforms his men from ordinary warriors into soldiers ready to risk all. In this respect, he is like Achilles, whose very presence on the battlefield meant the difference between victory and defeat.

But Gordon doesn’t give her readers a pure portrait of Confederate heroism in combat. She also shows the dark side of the Southern military. At the Battle of Fort Donelson, Forrest confronts for the Confederate officers who later deny him and his men ultimate victory by undercutting every success he achieves. First among these is Braxton Bragg, who was trained at West Point and who commands and fights by outmoded rules. As a result, Bragg and those who follow in his path suffer a paralysis of indecision because they fear to depart from textbook solutions and address real tactical problems.

In this early incident, the commanding generals have decided to surrender the fort which they have thus far succeeded in defending. Forrest — the instinctive soldier who embodies virtues lacking among the more refined generals — refuses to obey the cowardly order. Grasping the importance of Fort Donelson to the future of the War and believing the position is defensible, he is defiant:

“You can surrender the infantry,” he said, “but you can’t surrender my cavalry. I’ll take ‘em, out of it’s the last thing I do.”

In contrast to both Forrest and Bragg, who represent the strong and weak elements in the Southern will, the enemy is depicted in fleeting but significant glimpses. Unlike Forrest’s Confederate superiors, the Union generals know they can never achieve complete victory until Forrest has been contained. Sherman, the Confederacy’s most formidable adversary, recognizes that Forrest is the only inspiration for the continuance of the War in the West. Although Southern forces have been outnumbered and routed, successfill resistance nevertheless continues under Forrest. At this point, the Union forces pursue him alone, ignoring the rest of the Confederate Army. As Sherman says:

Go out and follow Forrest to the death… if it takes ten thousand lives and breaks the Treasury. ” [Forrest] opened his eyes and stared at the wall opposite. They said that the authorities at Richmond didn’t appreciate him. Well, he would take his praise, when he got any, from the Yankees. Sherman, for all his book learning, went right to the point….

In this single character of Forrest and in his relationships with the military bureaucrats and with his own men—-Gordon gives her readers not only a portrait of how the hero acts in the face of hostile invasion, but also renders in dramatic terms her idea of why the South ultimately lost the War. In Forrest’s conflict with the weak yet haughty Bragg, we see the failure of the bureaucracy to fight the kind of War that would have resulted in ultimate victory. It was Bragg—and his supporters in Richmond—who was ultimately responsible for Union victory.

A cautionary word to readers used to viewing the War through the eyes of Lee and the Army of Northern Virginia: Caroline Gordon came from Kentucky, spent much of her time in Tennessee, and shared the belief of her husband Allen Tate and her close friend Andrew Lytle that the Confederate government concentrated most of its resources in the defense of Richmond while fatally neglecting Tennessee, Mississippi, and the other western states, where the War was really lost.

Yet her quarrel was not with Lee or Jackson, who were aggressive generals, but with the likes of Braxton Bragg, cowards afraid to risk all when the chips were down. In the Allard family, Bragg has his counterpart in Fontaine, whose function in the novel is to provide a passive alternative to the actions of Forrest and Rives— heroes who go to war willingly. As Rives, following Forrest, takes his chances on the battlefield, Fontaine, like Bragg, is weak and ineffectual.

Consequently, he presides over a disintegrating community back home. Foraging Union soldiers plunder the plantation. The slaves are disloyal. he children become unruly. And this breaking up of order occurs because Fontaine is not man enough to prevent it.

Gordon does not content herself with the rendition of characters who embody the strengths and shortcomings of the Confederacy. She also distills the virtues and vices of the Union in her depiction of a single character, William Tecumseh Sherman.

Sherman, the embodiment of the Yankee spirit, has many of the qualities of the hero. He is courageous and is willing to do whatever is necessary to defeat his enemies. Yet in several significant ways he provides a marked contrast to Forrest. Lake the world he represents, he is cold-bloodedly pragmatic, a quality that enables him to make war on the civilian population in order to break the will of the Confederacy. Instead of representing the ideal of manhood, he is the New Man, the American of the future—a well-oiled machine who counts the mounting casualties without ever grieving for the flesh-and-blood people they represent. He signals the fading away of the Western hero—first depicted in the Iliad, finally defeated at Appomattox, a man like Achilles who is all too human, yet larger than life.

Nathan Bedford Forrest is such a man in None Shall look Back. Yet Forrest is not the primary hero of this novel, but merely the epic model for the novel’s real hero—Rives Allard— who represents the hundreds of thousands of Confederate soldiers who fought fiercely and bravely against overwhelming odds and almost prevailed. In Rives the reader sees the fictional recreation of figures like Willie Pegram and the Gallant Pelham, who sacrificed themselves willingly for the Lost Cause.

Allard gives his life at the Battle of Franklin, one of the bloodiest of the War. In this crucial encounter, Forrest’s men break for the first time ever under his command. Most are conscripts—literally captured and forced into battle—and consequently have no sense of duty or loyalty.

In the spreading panic—which bewilders Forrest and breaks his heart—Rives suddenly becomes a hero in the fullest sense, a soldier who mirrors Forrest’s own legendary courage. The line breaks, the standard Bearer flees with the colors; and it appears as if Forrest will at last suffer defeat. But Allard, long used to playing the ambiguous role of spy, suddenly commits himself:

Rives drew his pistol. The man was coming faster now. Rives aimed at the button on the wet jacket. The man coughed and began to fall. Rives swooped by, snatched the flag from him and hit the ground.

He rode back toward the front. Mortons guns were still firing but they stood alone except for the bending, dogged figures of the gunners. The infantry was pouring away in panic over the slope. Some men brandished weapons, others struck at the air with their hands, looked back over their shoulders, howled. Rives anger drenched his throat, beat in his temples. But he still had the flag. His fingers closed over the wood that was still warm from the dead coward’s hand. He set the pole hard against the pommel of his saddle, rode at them yelling and firing.

At this moment, Rives is killed. However, his death is by no means meaningless. He has rallied the troops and has also touched the heart of Nathan Bedford Forrest, who picks up the colors from the fallen hero, understanding for the first time the awful finality of death. Yet the General charges back into battle, fully mortal and even more frilly the hero.

At this point, Caroline Gordon switches back to the home front. There Lucy Allard, Rives’s wife, receives news of the death of her husband with the kind of tragic understanding typical of Confederate women. At this moment, which she has anticipated from the outset of the War, Lucy understands the total commitment that war demands when a way of life is threatened with extinction. War means death. Defeat means the loss of freedom and the imposition of an alien ideology on the land. So the death of heroes is necessary to defend the homeland.

The epic meaning of None Shall Look Back is perhaps best summarized by Andrew Lytle in his introduction to a late edition of his Forrest biography:

We do not know all the circumstances of Forrest’s triumph over himself. We know it only in his actions and because of one statement; he bought a one-way ticket to the war; that is, he had committed himself without reservations of goods or person. This is the very quality of heroism, because it is a triumph over death. It is also the secret of his triumph over great odds. Never thinking of himself, he is free to think of the enemy; and so he finds the weakness that will topple all of the weight and mass. There was never a greater half -truth than the statement that God is on the side of the biggest battalions. Moscow and Napoleon’s retreat stand for the refutation of this.

But in the end the hero always fails. He either dies as Roland dies; or the cause for which he fought is lost; or he wins the fight and the calculators who take over gamble it away, as with Forrest. Never tn the world are the powers of darkness finally overcome, for they inhabit matter; nor, without the conflict of the cooperating opposites of light and dark, good and bad, would life as we know it be.

So the end of Caroline Gordon’s great novel is predictable. The hero loses—one way or another. Rives Allard, like Pelham, is killed during a charge into the mouth of enemy artillery. Forrest’s victories are canceled by the spectacular defeats of lesser men like Braxton Bragg. And the way of life that Fontaine Allard stayed home to preserve is destroyed forever.

But we know all that from reading history, so why read fiction about the War Between the States? The answer to that question can be as simple or as complicated as you want to make it.

The simple answer: because good fiction writers tell good stories. Why read murder mysteries when you can read about murder in the morning newspaper? For the same reason.

A more complicated answer would address the fiction writer’s license to take the raw materials of history and construct a narrative that will bring historical characters and events into sharper focus and invest them with flesh and blood reality. Andrew Lytle’s biography of Forrest is dramatic and engaging (Lytle, after all, was a novelist at heart). Caroline Gordon, with her freedom to create characters and scenes in a novel, can bring the whole of Southern society to life through fictional scenes and fictional characters and at the same time keep the heroic action moving, thus telling us something more about Forrest’s epic struggle—its resonance in the minds and hearts of ordinary Southerners.

Novels can never replace genuine history, as Oliver Stone has amply demonstrated in his ideologically distorted movies. But fiction can shed light on history in ways that are valuable to serious readers. For this reason, Caroline Gordon’s None Shall Look Back is a must for anyone interested in the War Between the States and its tragic consequences. In her hands, the 19th-century South, in all its complexity, comes to life.

This piece was originally published in the 4th Quarter 1996 issue of Southern Partisan magazine.