When New York City’s Central Post Office opened in 1914, it bore the inscription that was to become the United States Postal Service’s unofficial motto, “Neither snow nor rain nor heat nor gloom of night stays these couriers from the swift completion of their appointed rounds.” Those couriers began their official rounds in July of 1775 when the Second Continental Congress established a chain of sixty-seven post offices throughout the thirteen former colonies and named Benjamin Franklin as the new nation’s first Postmaster General.

While thirty-two of those postal facilities were located in the seven Northern states, thirty-five were placed in the six states of the South, with Virginia and Maryland having the greatest number, fifteen and ten respectively. Prior to the adoption of a formal postal service, the first delivery of mail in colonial America, primarily correspondence to be sent back to Great Britain, was a municipal collection center that was opened at a Boston tavern in 1639. Later, a few semi-official mail routes were established between the colonies of Massachusetts, New York and Pennsylvania. In the South, however, most parcels, mail and other documents were delivered by private messenger services that mainly used slaves as their trusted carriers.

A more centralized mail system finally came to the colonies in February of 1691 when Thomas Neale was issued a grant by the British government to create a North American postal network. Neale was given the authority to establish postal facilities in all the thirteen colonies for the receipt and delivery of letters and parcels for an agreed upon fee. A central office was created in New York City with Andrew Hamilton, the governor of New Jersey, as Neale’s deputy postmaster. Within two years, while regular deliveries were being made from New England to Virginia, Neale’s service began to accumulate heavy debts. In fact, no postal system in America ever showed a profit until 1760 when Franklin instituted a series of drastic reforms.

As America grew, so did its postal system and within a little over half a century, the number of post offices had risen from the original sixty-seven to over thirteen thousand. After regular passenger and freight rail service began in Baltimore in 1827, the delivery time for mail began to shrink from weeks and days to just days and even hours. The transmission of news reports and other vital information was then reduced to minutes following the introduction of the first telegraph line from Baltimore to the nation’s capital in 1843.

Within a decade, the growing tensions that were developing between the North and South made the quick receipt of official correspondence and news reports even more vital. While the now numerous rail and telegraph networks provided rapid, even instantaneous, service to the eastern half of the United States, all such communication stopped at the Mississippi River. News and correspondence that had made it as far as the eastern banks of the Mississippi would sometimes take weeks to reach California by stagecoach or wagon train. Three men from Missouri, however, felt they had a solution to the problem.

In 1860, William Russell, Alexander Majors and William Waddell were the owners of the Central Overland California and Pike’s Peak Express Company. The firm ran stagecoach and freight lines from St. Joseph to California via a northern route that ran through Salt Lake City and Denver. At that time, the delivery of mail and telegrams from St. Joseph to San Francisco would take up to three weeks. Russell and his partners came up with the concept of using a relay system of fast horses over the northern route that could cut the delivery time to ten days. They called it the Pony Express.

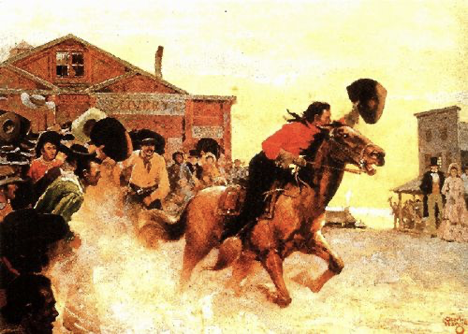

Over a hundred fifty stations were quickly set up, with eighty riders and four hundred horses put in service. The first rider, John Fry of Missouri, left St. Joseph on the evening of April 3, 1860, carrying forty-nine letters, five telegrams and a few newspapers. Just ten days later, the final rider, fellow Missourian Gus Cliff, arrived in Sacramento. In November, a run carrying the results of the 1860 presidential election was made in only seven days. While the Pony Express made good its promise of fast service and was partially subsidized by the federal government, it failed to win the U. S. mail contract and quickly fell into debt.

As his freight company had military contracts and was still owed money by the War Department, Russell contacted Secretary of War John Floyd for financial assistance. Even though Congress had not yet appropriated any funds for Russell’s company, Floyd gave Russell a written assurance of payment which Russell then used to obtain some short-term bank loans. When the loans came due and Russell’s funds had still not not been approved by Congress, it was suggested that he see one of Secretary Floyd’s relatives, South Carolinian Godard Bailey who was a clerk in the Interior Department.

At the time, Bailey was in charge of $870,000 in bonds that were used as a trust fund to make payments for treaty obligations the federal government had with various native tribes. At Floyd’s direction, Bailey removed the bonds from a safe and turned them over to Russell. The theft was discovered in late December by Interior Secretary Jacob Thompson and when Bailey was finally located, he implicated both Floyd and Russell. A District of Columbia grand jury indicted all three men but they never came to trial. The bonds were never located and the federal government had to replace the bulk of the trust fund two years later.

After his release, Russell continued to operate the Pony Express but when both transcontinental telegraph and railroad services were nearing completion, he ended the company in October of 1861. While the Pony Express had made history during its eighteen months of operation, it never made a profit. The line had also brought fame to some of its riders, most notably, “Buffalo Bill” Cody, but it brought nothing but disgrace and failure to Russell, Majors, Waddell, Bailey and Floyd,

After the Pony Express ceased operation and the freight line went bankrupt, Russell established a gold mine in Colorado and later a stock brokerage firm in New York but both failed. He returned to Missouri in poverty and died at his son’s home in 1872. In 1895, the equally penniless Majors was found by “Buffalo Bill” Cody who gave him a job in his Wild West show. Majors remained with Cody until his death in 1900. Waddell, on the other hand, had immediately retired from business and returned to his home in Lexington, Missouri, but misfortune followed him there as well. During the War, Waddell’s house was raided a number of times by Union troops and one of his sons was killed defending a slave. Waddell died in poverty in 1872.

Of the other two men involved in the bond scandal, Bailey returned to South Carolina, married Ann Lewis and joined the Confederacy. After the war, he and his wife relocated to what was then the Bronx area of Westchester County in New York where he became a member of the local police force. Bailey died there in 1877 with a Confederate Battle Flag carved on his headstone. As for Floyd, both the scandal and charges that he, after Lincoln’s election, had transferred large quantities of small arms and heavy ordinance to federal arsenals in the South, forced Floyd to resign from President Buchanan’s cabinet in December of 1860.

After Virginia seceded the following April, Floyd returned to Richmond and was commissioned a major general in the Army of Virginia, but he soon accepted a commission as a brigadier general in the regular Confederate Army. After a year of undistinguished service in the western theater, Floyd was relieved if his command by President Davis. The former governor of Virginia then returned home to reassume his rank of major general in the state’s militia. Within a year, however, Floyd’s health failed and he died in he summer of 1863.

In April of 1860, with the clouds of war gathering over the nation, regular mail and telegraph service was then making its way as far as the Mississippi River. In August of the following year, when those clouds had finally loosed their iron rain upon the South, virtually all such service then stopped at the Mason-Dixon Line. In February of 1861, however, the Confederate postmaster general, former U. S. Congressman John Reagan of Texas, had ordered the more than eight thousand post offices in the South to be placed under Confederate control. Reagan also reached out to Southern postal workers in the North to come to the South’s aid and several hundred responded to the call.

As the South had neither its own postage stamps nor the means to print them, U. S. stamps had to be used initially but by October, the Richmond printing firm of Hoyer and Ludwig had produced a five cent stamp bearing the picture of President Jefferson Davis, the first image of a living president to be placed on a stamp. Due to the poor quality of their stamps, Reagan soon gave the printing contract to the well-known lithographic company of Thomas De La Rue in England.

The first stamps and plates made by the London firm were shipped to America aboard a blockade runner but the ship was captured. A second shipment arrived safely in North Carolina the following April and was turned over to the new Richmond firm of Archer and Daly. John Archer was an experienced engraver who had worked for the American Bank Note Company in New York and had formed a partnership with Joseph Daly, a wealthy Richmond businessman. The company also produced their own plates for a variety of high-quality stamps.

During the war, both the North and South established postal facilities at military bases, as well as a field distribution and collection system. If any in the military did not have a stamp, both sides also allowed them to merely write “soldier’s mail” on the envelope and the postage would be collected from the recipient. Mail to and from both Confederate and Union prisoners of war, as well as some civilian correspondence, was also allowed through the lines under a flag-of-truce system. All such mail, however, was subject to heavy military censorship.

At the start of the war, expenditures by the South’s mail service were three times its revenue but by the end of 1863, Postmaster Reagan had made the Confederate service completely self sufficient . . . something that still eludes the U. S. Postal Service.

After the Confederate government abandoned Richmond in April of 1865, Reagan was made secretary of the Treasury but he and President Davis were taken prisoner the following month in Irwinville, Georgia. and imprisoned at Boston’s Fort Warren for two years. Reagan returned to Texas after being pardoned by President Andrew Johnson and in 1886, he was elected to the U. S. Senate where, as a touch of irony, he became chairman of the Post Office Committee.

Interesting. I was aware that the Pony Express failed financially but not the fate of the men who had formed it.

Abbeville Institute has the most interesting articles on issues that I had never considered in these ways. Thank you!

that’s what happens when you make up your own version of history…