A review of Our Comfort in Dying (Sola Fide Publications, 2021), R. L. Dabney and Jonathan W. Peters, ed.

Dabney “was fearless and faithful in the discharge of every duty. . . . [He] was a Chaplain worth having.” –Col. Robert E. Withers, Commander, 18th Virginia Infantry Regiment, 1861

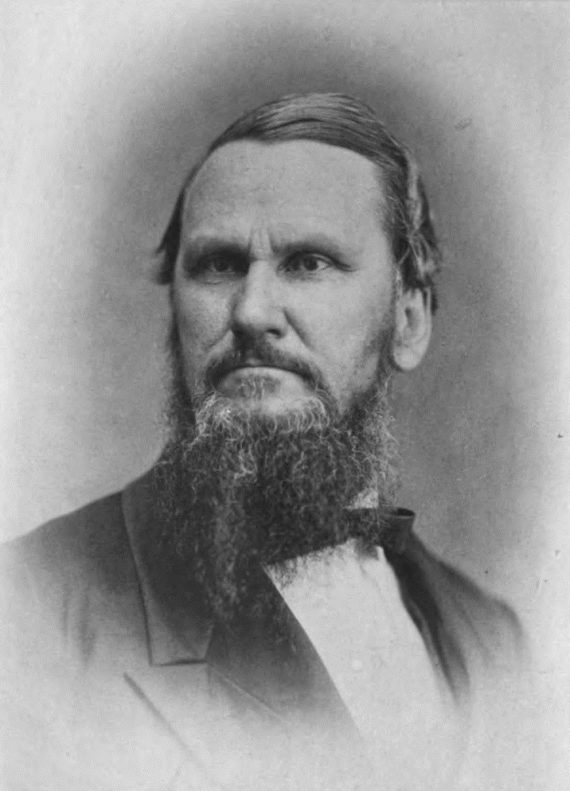

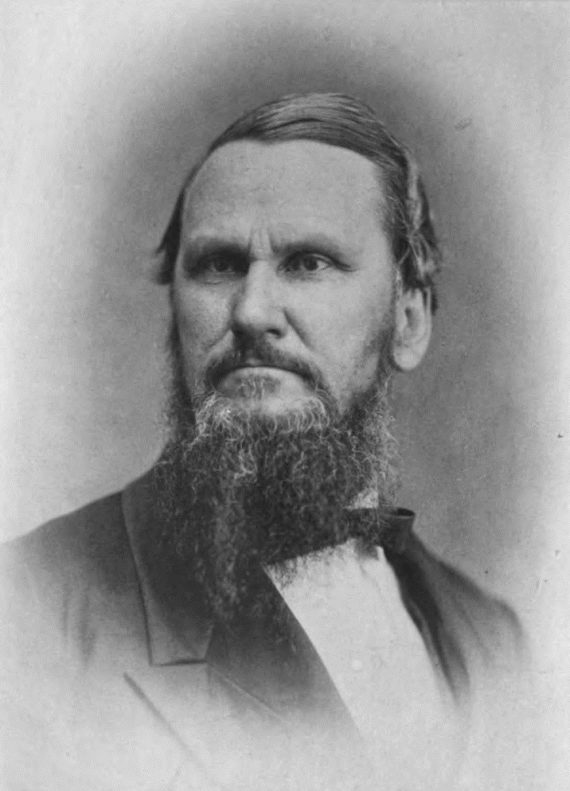

In the current American dystopia, the life and ministry of an Old School Southern Presbyterian minister such as Robert Lewis Dabney (1820-1898) is likely to be dismissed out of hand by many – though it will be to their shame – regardless (or perhaps in part because) of his towering intellect, unshakable convictions grounded in the Bible and its principles, and prescience regarding ideological afflictions (among them feminism and socialism) that came to fruition in later generations.[1] But for more mature students of history and culture who are willing to examine a man’s life in the context of his own time and place and whose reliance was on the whole counsel of God, a newly released work – with the main title, Our Comfort in Dying – may be highly recommended as an addition to one’s devotional and Southern history shelf at home. Comprehensively and beautifully edited by Jonathan W. Peters, including citations with enriching detail (such as excerpts from letters of soldiers who heard Dabney preach in their camps), the work makes available 20 of Dabney’s sermons, all of them preached in Virginia, most of them between May 1861 and June 1863.

Almost 25 years ago, as Presbyterian pastor David Coffin labored on his doctoral dissertation, haunting the archives of historic Union Theological Seminary in Richmond, Virginia, Coffin discovered a package “wrapped in a distinctive paper band.” Upon examination, he counted 12 manuscript sermons of Dabney’s. They apparently had been undisturbed since the 1880s or 1890s, by which time Dabney had completed the writing out of the sermon texts which he had first preached from an outline format by memory. Several were published in Presbyterian periodicals in the late 1800s, but others probably had not been heard or read in any form since Major R.L. Dabney’s voice echoed through the verdant camps of the Virginia volunteer regiments which gathered to worship the “captain of the host of the LORD” (Joshua 5:14). On at least one occasion, Dr. Dabney preached to young Virginians – some of whom never again were to hear the words of life offered to them – within the sound of the enemy’s artillery only a few miles away.

Realizing these sermons were of great value especially to students of Dabney’s preaching, Union seminary digitized the 12 sermons and placed them on their website. (Does one dare consider what might have befallen these sermons had they been uncovered in the madness of 2021?) In early 2020, Jonathan Peters, an administrative assistant at Harford Christian School, in Darlington, Maryland – and a costumed Gettysburg tour guide – encountered the army sermons while studying the life of Dabney. In the following months, Peters transcribed the 12 and included 6 of Dabney’s previously published sermons. Adding 2 more unpublished Dabney sermons from Union’s archives (both of those were pre-war), Peters compiled the 20 and edited them for publication, which now happily comes to fruition.

Dr. Dabney preached sermons 1 through 5 between 1851 and the close of 1860. In sermon 2, “Secular Prosperity,” Dabney observed, “The past does not furnish an instance, in which the spiritual health of the church has survived a season of high secular abundance.” A few minutes later, he added, “Dearly beloved: have not your steps in advance towards heaven been chiefly taken in the season of private affliction, on the sick bed, in the chamber of bereavement, beside the dying couch or the fresh graves of those you love?” The decade prior to the devastation of the 1860s witnessed economic prosperity for many, and the minister admonished the Richmond, Virginia, congregation, “. . . our present ease will be our ruin. . . . Can you reasonably flatter yourselves that you shall be an exception to all previous history?” His answer to the dangers of secular prosperity was found in missions: “We must burst forth on every side, into a magnificence of missionary enterprise, as marvelous as the growth of our commerce, arts, agriculture, and general prosperity.”

From early June through late August of 1861, Dabney took a leave of absence from Union Theological Seminary where he taught in order to minister mainly to the 18th Regiment, Virginia Volunteers, which included many Hampden-Sydney men. The first significant engagement of the war, the First Battle of Bull Run (or Battle of First Manassas), took place on July 21, 1861. It was there, following Federal advances throughout the morning, that the retreating Virginians rallied around the brigade of Brig. Gen. Thomas J. Jackson, known to the world thereafter as “Stonewall.”

In the very month of First Manassas, in sermon 9, “Immediate Decision” – which Dabney preached multiple times during the war – he asked, “If indecision is disastrous in temporal affairs, what must not be its mischief, in the more momentous concerns of the soul?” He warned his listeners, “The idol which divides your convictions with Jehovah, is not, indeed a pagan image. It is that universal object of the worship of unconverted men, this world, with its pleasures, riches, honors. For that to which you look for your prime happiness, which you seek with supreme devotion, and in which you rely as your chief good, is practically your God.” Near the end of this sermon, Dabney implored the soldiers, “O perishing man, cast out of thy heart thy self-will, thy besetting sins, and thy delays, before they sink thee in the burning lake.” Thanks to Peters’s editorial labors, readers learn that Jedediah Hotchkiss (1828-1899), a skilled topographical engineer who served under Jackson and later, directly under Robert E. Lee, heard this sermon by Dabney on two occasions, in 1862 and 1864. In later life, Hotchkiss was active in the Second Presbyterian Church of Staunton, Virginia.

Dabney preached sermon 11 in late August 1861 before the 27th Regiment of the Stonewall Brigade. In the sermon which gives this book its title, “Our Comfort in Dying,” Dabney alluded to the ninth chapter of the Book of Hebrews: “In the season of health and prosperity it will be wholesome for us to remember that it is appointed unto men once to die. . . . He alone of all the universe has fathomed the deepest abysses of death, has explored all its caverns of despair, and has returned from them a conqueror.” He closed with words as needed today as they were amidst the internecine combat of the 1860s: “Call on Christ, then, today, in repentance and faith, in order that you may be entitled to call upon him in the hour of your extremity. Own him now as your Lord, that he may confess you then as his people.” At the end of the summer, Dabney debated whether to continue his chaplain service or return to teaching at Hampden-Sydney; for several reasons, including an outbreak of typhoid fever which had scattered the soldiers beyond his ability to visit them, he decided on the latter.

The following spring, Dabney acceded to the repeated, earnest invitations of Stonewall Jackson to come and serve as his “parson-adjutant” – officially he became Jackson’s chief of staff. In this capacity, Dabney served with Jackson between April and July 1862. On May 8, Jackson’s forces fought at McDowell, one of the engagements of his famed Valley Campaign. Four days later, on Monday, May 12 – the day prior was the Christian Sabbath, but the aftermath of the McDowell operation had precluded its observance – the general, who held the holy day in the highest regard, allowed his men half of the day as a rest near Franklin (now West Virginia) and invited Dr. Dabney to preach. In sermon 13, “Public Calamities Caused by Public Sins,” Dabney preached in the “verdant meadow of the South Branch, beside a cluster of haystacks.” Major General Jackson and his staff, and General Francis H. Smith, the superintendent of the Virginia Military Institute where Jackson taught before the war, attended. Dabney began with words that shed light on his views of the faithful gospel ministry, as edifying today as in 1862:

Men ask anxiously, “When will the war end?” I reply, when God has gained those purposes, which he proposes to himself in it. It is not we, nor our enemies, who began this war, or who can end it; but God. That it is his agency, is proved by this fact: that the struggle has notoriously been precipitated against the purposes and expectations of both parties. I shall then attempt to give an answer to this anxious question, from Sacred Scriptures. But do not fear that I propose to inflict upon you that nuisance, so justly hateful to all Christian souls, a political sermon. Far be it from me to make the sacred pulpit a partisan in any secular debate, or an advocate of any social plan or advantage. But the attempt will be made to apply God’s own truth to the explanation of his providences towards us. Were this oftener done, we should see more life and interest in the Sacred Scriptures, and should derive more profit from the lessons of our Father’s chastisements.

By July 1862, Dabney fell ill and was forced to take sick leave and return home. His sufferings from the “camp fever” continued, however, and he was forced to resign from his position on Jackson’s staff, which his commander reluctantly accepted. By the end of the year, Dabney’s health had been restored somewhat.

In sermons 17 and 18, Dabney preached on the occasion of the remembrance of a fallen compatriot. Offering correction to today’s tendency to pretend that death is something less grievous that what it is, in “The Christian Soldier” (December 14, 1862) he spoke to a gathering that mourned the loss of a friend of Dabney’s, the heroic Abram C. Carrington (Virginia Military Institute, Class of 1852), killed on the sixth day of the Seven Days’ Battles outside Richmond:

Death, and especially what men call a premature death, must ever be regarded by us as a natural evil. . . . The very instincts of man’s animal nature abhor it, and his earthly affections shudder at the severance which it effects between them and their dear objects. So, the death of friends cannot but be a felt bereavement to survivors, be its circumstances what they may.

Six months later, in early June 1863 Dabney preached a commemorative sermon following the death of his friend and former commander, Stonewall Jackson, whose mortal wounding on May 2 at Chancellorsville marked the Confederacy’s high tide. “Our dead hero is God’s sermon to us,” Dabney said. Faithful to his solemn charge, Dabney continued, “I stand here, as God’s herald, in God’s sanctuary, on his holy day, by his authority. My business is, not to praise any man, however beloved and bewailed, but only to unfold God’s message through his life and death.” In his sermon entitled, “True Courage,” Dabney addressed several types of courage, one of which he said “. . . is the moral courage of him who fears God, and, for that reason, fears nothing else. . . . Jesus Christ is the divine pattern and fountain of heroism. Earth’s true heroes are they who derive their courage from him.” Could there be any message more desperately needed in today’s culture than this?

Under God’s providence, this book appears at a most opportune moment: statues are vandalized or hauled off, buildings renamed, and lies propagated by the one “who is pure in his own eyes” (Proverbs 30:12). R.L. Dabney is well known as the adjutant-chaplain of the famed Jackson; and he was Stonewall’s earliest biographer. Exactly 50 years from Jackson’s mortal wounding, on May 2, 1913, the New York World wrote, “A united nation can be proud that he was numbered among her sons.”

But Jackson’s name is badly maligned today according to CRT’s divisive, pernicious poison. Thankfully, every week more Americans are awakening to the barbaric, dignity-depriving, and soul-destroying ideology of what some have rightly called “Critical Rac-ist Theory.” (Such terms are not hyperbole: any ideology that seeks to destroy the foundation of civilization – the nuclear family – is, in fact, barbaric; one that views all persons either as oppressors or oppressed, is dignity-depriving; and the denying of individual responsibility for one’s actions, is soul-destroying.) Our Comfort in Dying points its readers to much better things – true, honorable, right, and pure, as the Apostle Paul wrote to the Philippians (4:8).

Bottom line: if the book burners come a’knocking at your door – for the sake of government efficiency, perhaps the vaccine checkers can pull double duty here! – this little gem of truth, high courage, and authentic manliness should be one of those works you have tucked safely behind a panel or under a floorboard, comprising part of what noted journalist and author Rod Dreher’s Live Not By Lies refers to as one’s “small [fortress] of memory” in an era of government-led “forced forgetting.” You’ll be glad you did.

[1] For one example, see Dabney’s “The Public Preaching of Women,” The Southern Presbyterian Review, Oct. 1879. Dabney began as follows: “In this day innovations march with rapid strides. The fantastic suggestion of yesterday, entertained only by a few fanatics, and then only mentioned by the sober to be ridiculed, is to-day the audacious reform, and will be to-morrow the recognized usage. Novelties are so numerous and so wild and rash, that in even conservative minds the sensibility of wonder is exhausted and the instinct of righteous resistance fatigued.”