From Cleburne and His Command (1908).

From the foundation of the American Republic the Irish people have largely contributed to its upbuilding. Want of space forbids a recital of their services in the pulpit and in the forum, in commerce, agriculture, finance, and government. The military is the only one which can be treated in any degree of detail, for in this the natives of the Emerald isle have ever been conspicuously distinguished. Of this is written by an accomplished Confederate soldier: “Strange people, these Irish. Fighting every one’s battles and cheerfully taking the hot end of the poker, they are only found wanting when engaged in what they believe to be their national cause. Except the defense of Limerick, under the brilliant Sarsfield, I recall no domestic struggle in which they have shown their worth.”- (Taylor, “Destruction and Reconstruction.”) And Gen. D. H. Hill says: “Poor Pat, he has fought courageously in every land, in quarrels not his own.” And the same author, to illustrate the esprit-de-corps of the Irish soldier, his pride in his command, and affection for it, relates that he found on the field of Chickamauga a desperately and shockingly wounded Irishman, to whom he said: “My poor fellow, you are badly hurt. What regiment do you belong to?”

“The Fifth Confidrit, and a dommed good rigimint it is,” said the wounded man promptly.

To go no further back than the war between the States, it is found that those of Irish birth or descent, on the Federal side, were Sheridan, Meagher, and Sweeney; on the Confederate side, Cleburne, Finnegan, and Dick Dowling. And in both armies thousands of less rank, or none at all, while not so conspicuous, were none the less gallant. But among all these the career of Patrick Cleburne was most brilliant and phenomenal. From the local reputation of a young lawyer of high standing, Patrick Ronayne Cleburne, in less than four years, rose from a private soldier, and at the early age of thirty-seven years died holding the rank of major-general, and with a military record to be envied by the most illustrious, and after hiving gained from the public the well-earned sobriquet “Stonewall of the West.” But by his idolizing command, he was only spoken of as “old Pat.” ”

It may appear strange that one so prominent should not have had more mention among the leaders of the South, and that he is so little known beyond the Western Army. This seeming omission or neglect can in a measure be attributed to the fact that he was killed in the last months of the war, and the surviving participants, after the war closed, were too busy repairing their broken fortunes to pay much attention to literary affairs. It has required the lapse of decades to give suitable opportunity for historical or biographical justice to those who staked their all for the South.

The following sketch was written for the Arkansas Gazette, by Judge L. H. Mangum, Cleburne’s law partner before and his aide-de-camp during the war:

Gen. Patrick Ronayne Cleburne was the third child of Joseph and Mary Ann Cleburne. He was born at Bridgepark Cottage in the county of Cork, ten miles west from the city of Cork, March 17, 1828. His father was a physician of considerable eminence in his profession; a graduate of medicine of the University of London, and in surgery of the Royal College of Surgery, Dublin. He was of an old Tipperary family. * * * Dr. Cleburne was noted for his generosity and unselfishness; was beliked alike by rich and poor; and left behind him a name which lives in the memory of the old inhabitants of West Cork.

His wife was the daughter of Patrick Ronayne, Esq., of Anne-brook, on the Great Island, Cork, after whom General Cleburne was named, a name that has survived through six generations of that family. On his mother’s side General Cleburne was therefore of an old Irish stock, and being born on St. Patrick’s Day his claim to the ancestral name rests upon a double association. By a singular coincidence the name which was destined in after years to shed splendor on the annals of heroism and arms was crowned in its very birth by the three ideas dearest to the Irishman who bore it—patriotism, pride of honorable lineage, and filial love.

Patrick was but little over two years of age when his mother died. His father’s second marriage found him still a child, but he was kindly and tenderly treated by his step-mother, with whom he was a favorite. Dr. Cleburne’s first family consisted of three sons and one daughter—William, the eldest, now (1886) engineer in charge of the Oregon Short Line Railway; Anne, now Mrs. Sherlock, formerly of Cincinnati, Ohio; Patrick Ronayne, the subject of this sketch; and Joseph, the youngest. All of these are now (1886) living except Patrick.

The second marriage was contracted about a year after the first Mrs. Cleburne’s death, with a Miss Isabella Stuart, daughter of a Scotch clergyman. The children by this marriage were four— Isabella, Edward Warren, who went to sea and died of yellow fever on the west coast of Africa; Robert Stuart, and Christopher. This last named half-brother followed General Cleburne to America, who at the beginning of the war bought his younger brother a fine horse and sent him to General Morgan. He declined, after his own rule, to furnish any letters of introduction, but Morgan soon found the worth of the young man, and he became captain in the Confederate Second Kentucky Cavalry. He was killed at the battle of Cloyd’s Farm, near Dublin, Virginia, May 10, 1864, in the twenty-first year of his age. In the words of his commanding officer, “He rests in the State whose valor has given luster to the age, and his memory is cherished by his comrades as that of the brave, chivalrous and true man.’’

Young Patrick received instruction at home from a tutor until he was about twelve years of age, when he was sent to a school in the neighborhood kept by a clergyman of the Established Church named Spedding, whose memory is preserved in the recollections of his pupils by the terrors of his rule rather than by the force of his scholarship, or by the taste for learning which his system of instruction inspired.

Patrick was fond of boyish adventures, but he avoided companionship and preferred his dog, his horse, his rod or his gun to other company. Even in those early days he was noted for his high sense of honor and his keen sense of disgrace. In literary taste he was fond of history, travels, and poetry, but whether it was due to some peculiar mental inaptitude or to the disgust created within him by the pedagogue who had dealt out the classics by the rule of iron, he was very deficient in Latin and Greek.

His father was in the receipt of a good income from the practice of his profession, but had one expensive taste in a fondness for amateur farming. He cultivated a farm of 500 acres on this principle and practiced his profession at the same time. As he was a better doctor than farmer the result was that what the profession brought in the farming absorbed. When he died he left but a small estate to be divided between his widow and his eight children. Two years later, when Patrick was eighteen years old, he turned his thoughts to the selection of an occupation for life. He had a taste for chemistry and he chose the business of a druggist, intending to make that a stepping-stone to the study of medicine. With this in view he apprenticed himself to a Dr. Justin, who kept a drug store in the little town of Mallow.

Had chemical tastes or pharmaceutical studies been the only requisites for advancement in that line, the future general might have lived a respectable Mallow druggist or been a dispensary doctor in some quiet Irish village. To secure a diploma, however, it was necessary for him to pass a severe examination in Apothecaries’ Hall, Trinity College, Dublin, which included Latin, Greek, and French. Here the Societies of Apothecaries attacked him in his weakest point, and here the embryo hero met the first and only defeat of his life. The sense of disgrace overwhelmed the boy of eighteen, and resolving that his family should never know more pf one who, as he conceived in his infinite humiliation, had brought a blot upon the family escutcheon, he immediately enlisted without communication with his friends and became a soldier in the Forty-first Regiment of infantry, then stationed in Dublin. It was rumored at the time that these troops would be ordered on foreign service, and this thought influenced him in selecting that particular regiment.

A year elapsed before his friends knew where the boy was, and the information came then from the family of Captain (now General) Robert Pratt. This officer was the son of the rector of the parish adjoining that in which the Cleburne family lived, and the rector was a warm personal friend of Dr. Cleburne. Captain Pratt was not in command of the company to which young Cleburne was attached, and it was only by accident that Patrick’s identity was discovered. He has been heard to say with emphasis in alluding to this incident of his life that he would have enlisted under an assumed name had he known of Captain Pratt’s presence in the regiment.

The Forty-first was not sent out of the country and the young soldier’s life was uneventful. After above three years’ service he had been promoted through the grades of lance-corporal and corporal, but further promotion had been checked by the escape of a military prisoner whom he had in charge. Captain Pratt had secured his transfer to his own company and showed him many acts of kindness and courtesy uncommon in those days between a commissioned and a non-commissioned officer. When Cleburne made up his mind to quit the Army, Captain Pratt remonstrated with him strongly and assured him if he remained he would ere long win a commission. The brilliancy of General Pratt’s subsequent career in India and the Crimea gives weight to the opinion formed thus early of Cleburne’s soldierly qualities and capabilities.

Notwithstanding this advice, however, Cleburne, at the age of twenty-one, advised with his brothers and sister, arranged plans to obtain what means he could from his father’s estate and his mother’s fortune, purchased his discharge and prepared to take leave of home and country and seek his fortune in foreign lands. In company with these relatives he sailed from the harbor of Queenstown, November 11, 1849, in the bark Bridgetown. The voyage in a slow sailing vessel was monotonous but not devoid of pleasure. It was Christmas Day when the vessel entered the mouth of the Mississippi.

Sir Thomas Tobin, manager of the Ballincolleg Powder Mill, had furnished the family with a letter of introduction to Geo. Currie Duncan, at that time president of the Carrolton Railroad, and a prominent citizen of New Orleans. This letter was indirectly influential in deciding the future destiny of the strangers. Cleburne, impatient of introductions and acting on the principle of his life, that a man should depend on himself and not on others, declined to wait the result of the letter, pushed on to Cincinnati, followed two days later by his elder brother and sister. There he found employment in the drug store of a Mr. Salter on Broadway, with whom he remained about six months, when, receiving more remunerative offers, he removed to Helena, Arkansas.

From the time Cleburne went to Helena he seemed to feel he had found a congenial home. The rich soil, the diversified landscape, and the noble river flowing in majestic tides of wealth and power at its base offered inducements both to the man seeking his fortune and to the lover of nature. People who were open and frank in nature, cordial in manners, and full of courage and enterprise gave the young Irishman society which echoed his own sympathy. He easily won his way into fellowship and popularity, and early laid the foundation of that popularity he wielded at a later day.

Entering the drug store of Grant & Nash as a prescription clerk, he devoted himself assiduously to his profession till 1852, when he purchased Grant’s interest in the business, and the firm was known as Nash & Cleburne. He was a hard student, both in his profession and in general literature. He joined and took great interest in a debating society formed by the young men of the place. Among these were Hon. John J. Horner, J. M. Hanks, Gen. J. C. Tappan, and the late Mark W. Alexander, men who afterwards became prominent in affairs and achieved distinction in their several walks in life. With such associates and competitors Cleburne held an honorable record. He was a ready and effective debater. Oratory charmed him and he devoted himself diligently to its pursuit. He soon became conspicuous for his oratorical abilities. In 1854 he was chosen orator at a celebration held by the Masonic fraternity of which he was already a bright member, and acquitted himself with such credit as to win general mention and applause. About this time he was persuaded by friends, especially by Dr. Grant, his former employer, to study law, and, selling out his interest in the drug business, he became a law student in the law office of the late Hon. T. B. Hanly. In 1856 he formed a law partnership with Mark W. Alexander, under the name of Alexander & Cleburne. In 1859 Alexander was elected circuit judge. The partnership of Cleburne, Scaife & Mangum was then formed.

While Cleburne was not a brilliant lawyer he had all the elements of success and distinction in this profession. His reading was careful and extensive, his application constant, his judgment clear, and his earnestness, always a marked characteristic of the man, clothed him with real ability. He was scrupulously honest and upright, stood well among his brother lawyers, and commanded not only a good practice but a wide and deep respect among the people. He dealt largely in lands, and at the beginning of the war was himself a large land owner. While he was always alert and eager in his professional duties, he identified himself thoroughly with all the interests of his city and section. He was known as a public-spirited citizen, quick in sympathy, ready of hand, lover of his adopted home, charitable in every impulse of his soul, and a friend of the poor. At no time in his life did he display more heroism than in 1855 when Helena was visited with a terrible scourge of yellow fever. The public generally was stricken with a panic and all that were able to go were flying in every direction to save their families from the dread contagion. But Cleburne remained in the fever-smitten place, going in daily rounds among the sick and helpless, nursing them, and soothing as far as possible the grief of the living and the last hours of the dying. His unselfish devotion at this time greatly endeared him to many hearts.

When Cleburne came to Helena he was an ardent Whig, a regular reader of Prentice’s Louisville Journal and the old National Intelligencer. His best friends were in the habit of ridiculing the idea of one of his nationality being a defender of federalism and railing at him as the “Irish Whig.” He met these tilts with perfect good humor, but always gave shot for shot. The discussions that passed in these days in the offices and along the streets of Helena when political discussion became warm would afford interesting reading to those who survive, and with whom those times have now passed into history. With the organization of the Know Nothing party the stubborn defender of Whig politics laid down his arms. He became a Democrat and remained steadfast in that allegiance to the day of his death. In religious faith he was an Episcopalian. For a succession of years he was chosen vestryman in St. John’s Church, Helena.

Physically General Cleburne was of a striking appearance, although he would not come in the category of “handsome men.” He was six feet in height, of spare build, with broad shoulders and erect carriage. In his large gray eyes the gleam of sympathy and the sparkle of humor were most often seen and they grew dark and stern in danger or battle. He was a man of great activity and of great powers of endurance. He was not a graceful man. In general society his manners would frequently be pronounced awkward or stiff. He was naturally modest in his own opinion of himself, and this often lent an appearance of diffidence and embarrassment to his actions. Very sensitive to the opinion of the world, his inborn pride rebelled against the admission or manifestation of it. This shyness was never more apparent than when in the company of the gentler sex, yet no man ever loved woman’s society more or held woman’s name in greater reverence. He was not a good conversationalist except when in the company of congenial friends whose intimacy freed him from all shackles of embarrassment. He was much given to fits of absentmindedness, his dreamy, poetic nature seeming often to beckon him away from present surroundings and realities. Yet, with all this, when duty pressed his faculties seemed tireless, unsleeping. And when the earnestness of the moment obliterated all thought of self and the occasion demanded dignity, no one showed more conspicuously than did Patrick Cleburne that nobility of nature which makes nobility of manners.

The most pronounced characteristic of the man, to those who knew him best and saw him in all the aspects of life, was his courage. He had, indeed, the lion’s heart. He was absolutely indifferent to danger and was as cool when exposed to it as in the most peaceful moments of his life. He never grew noisy or furious, never exhibited the slightest form of bravado, and he never quailed before odds or difficulties. He went where duty called, calm and determined. He performed the behests of duty without question or fear, and in the performance of it his mind and his arm acted with the rapidity and force of lightning. In all the relations of private life he was what he afterwards showed himself to be in tent and field.

Thus the opening of war days found Pat Cleburne, days when the blackest cloud that ever loomed on a nation’s vision gathered on his horizon and that of his fellow-countrymen, days when every young man buckled on his armor with fierce and eager delight and rushed forth to meet its baptism of fire and death. Cleburne was not a laggard then. Among the first he stepped to the front, and from the first he took prominent rank. During the summer of i860 a military company was formed in Helena, composed of the flower of the young men in the city and county adjacent. It was called the Yell Rifles, in honor of Colonel Archibald Yell, who fell at the head of his regiment at the battle of Buena Vista, Mexico. Cleburne was chosen captain, with L. O. Bidwell, E. H. Cowley, and James Blackburn as lieutenants. A fellow-countryman of Cleburne’s, named Calvert, who had been a sergeant in the United States Army, was employed as drillmaster. Calvert was a fine and thoroughly disciplined soldier, afterwards rising to prominence as a major of artillery, and under his efficient instruction the Rifles became a splendidly trained body of troops. It was one of the first to offer its services to the State in 1861, but before going into service was reorganized with Cleburne still as captain, E. H. Cowley, first lieutenant; L. E. Polk (afterwards brigadier general), second lieutenant, and James F. Langford, third lieutenant.

The Yell Rifles thus officered were, with other companies, ordered by the Governor of the State to rendezvous at Mound City, Crittenden County. At Mound City, in May, 1861, was organized the first Arkansas regiment of State troops. Through some confusion the Confederate records show two Arkansas regiments called the Fifteenth,* but this first regiment of State troops was the Fifteenth Arkansas of the Western Army. The following companies formed this regiment: Yell Rifles, Captain Cleburne; Jefferson Guards, Captain Carleton; Rector Guards, Captain Glenn; Harris Guards, Captain Harris; Phillips Guards, Captain Otey; Monroe Blues, Captain Baldwin; Napoleon Grays, Captain Green; Tyronza Rebels, Captain Harden. In the organization of this regiment Cleburne was chosen colonel; Patton, lieutenant colonel; Harris, major, and Dr. H. Blackburn, surgeon. * * *

L. H. Mangum was appointed adjutant of this regiment.

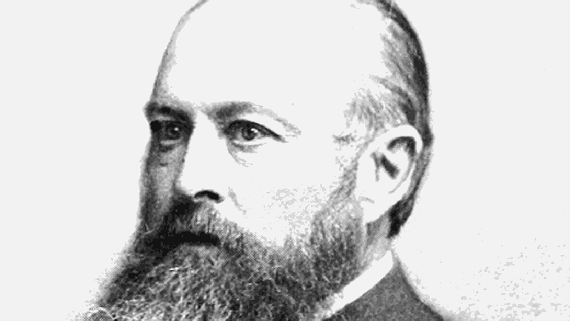

In describing Cleburne’s personal appearance one writer says:

In person he was about five feet nine or ten inches in height, slender in form, with a wiry, active appearance. His forehead was high and broad, high cheek bones, cheeks rather hollow and face diminishing towards the chin, the upper part being more massive than the lower. His hair, originally black, became tinged with gray, as was his delicate moustache and imperial. Eyes of clear steel gray in color, were cold and abstracted usually, but it needed only the flame of battle to kindle them in intensity, to stir the depths of his strong nature and show forth a soldier for stoutness of heart, for stubbornness of fight, for shining valor and forgetfulness of self, rarely to be matched.

Though a member of the Episcopal Church he seldom talked of religion, always respecting it, whether as an institution or a personal opinion. In his diary, January i, 1862, he wrote: “My God! whom I believe in and adore, make Thy laws plainer to my erring judgment, that I may more faithfully observe them, and not dread to look into my past.” While not a fanatic on the subject, he abstained from the use of tobacco and liquor, and by precept and example tried to impress upon others his reasons. These reasons were that during the war he felt responsible for the lives of his men, and feared the possible effect of intoxicants, for the proper discharge of his duties. He also said that a single glass of wine would disturb the steadiness of his hand in use of the pistol, and effect his calculations in playing chess, a game in which he was an adept.

Of firm convictions, strong personality, and unswerving loyalty and devotion to his friends, this last trait came near causing an early termination of Cleburne’s career. One of his associates became engaged in a controversy with a man bearing the reputation of a “dangerous man.” Cleburne had no interest at stake, but, Irishman-like espoused the cause of his friend “in a quarrel not his own,” drawing upon himself the wrath of the desperado, who publicly swore vengeance against Cleburne. Cleburne was well known to be quick and expert with the pistol and it was equally well recognized that a front attack upon him would be extremely dangerous. While Cleburne was walking the street of Helena, without warning a dastardly attempt to assassinate him was made. A shot was fired from a door-way he was passing, the bullet entering his back and going entirely through his body. Desperately wounded as he was, his will power enabled him to draw his pistol and kill his assailant before he himself fell to the side-walk. His recovery was despaired of, but his indomitable will to live greatly, if not entirely, tended to his recovery, after months of confinement to his bed.

From the time of Mr. Lincoln’s election Cleburne felt convinced as to the dissolution of the Union, but advocated secession through the united and concerted action of the slave-holding States in convention. He regarded the impending war as a struggle on the part of the South for liberty and freedom to control their own domestic affairs, as he believed was provided for under the Constitution.

Patrick Cleburne was one of Shelby Foote’s favorite General’s, or his favorite altogether. In reading and learning as much as I could about what happened in that war, the battle of Franklin, the whole Tennessee campaign near the end was one of the latter things I learned and took in. The whole war, from beginning to end was just unbelievable, every aspect of it. But, the campaign that General Hood led through Tennessee 1864-1865, no words; again, just unbelievable. General Cleburne and the rest, just gave it all they had, and then some.