I’ve learned a good deal about [Edgar Allan] Poe’s paternal and maternal backgrounds; I had never really pursued that; the biographies don’t. But I found that Poe’s grandfather had immigrated to America in about 1750 from Drung, County Cavan, Ireland. To put that on the board for you, that’s about 75 miles Northwest of Dublin, so it’s sort of in the center of things. There, Poe’s people were farmers, and interestingly, if you look up County Cavan today on its website, it calls itself a place of “lakes, pools, and bogs.”

You know where I would go with that if you read Poe’s poetry and fiction. A tarn is a kind of dark pool and water is everywhere, and we South Carolinians have always said, “Well, he stayed at Fort Moultrie and he liked the swamps of the Low Country,” and so forth and so on, and of course, there’s that. But then there’s also County Cavan, a place of lakes, pools, and bogs, a watery place. One’s tempted to ascribe Poe’s propensity for lakes, pools, and tarns to this cultural inheritance, or at least we can make the case. The Irish way of writing “Poe” puts two dots over the “ë.” (And I put that on the board for you). I guess you pronounce it “Po-ee” because it’s the same as Brontë (“Bront-ee”). (I put that on the board too). Emily Brontë, Charlotte Brontë, you know, the Brontë sisters, and Reverend Brontë in Yorkshire, England with his three famous daughters, came from Ireland too. And that, I think, explains why I’ve always liked Wuthering Heights the best of all of [the books from] that time. Emily Brontë’s Wuthering Heights to me is really one of the best of the English works of its day.

Poe biographers from Arthur Hobson Quinn in 1941 to Jeffrey Meyers in 1992 have noted his Irish lineage, but only in passing. Both choose only negative Irish traits, the main one being his love of alcohol and say, “Well, you know how these Irish are. Poe was a drunk and Irish are drunks.” And that’s about as far as they go with the Irish background. [If it’s Irish] it’s okay to pick out a negative quality. Sort of sounds like the way we do Southerners, right? But if it’s a positive trait, it’s American; if it’s a negative trait it’s Southern. Well, Meyers places Poe outside an Irish pub in Baltimore in his last days. He says “that’s so very appropriate.” Well, it is, if you know your heritage. I would go to an Irish pub if I was an Irishman or conscious of my Irish background. I’ll say more about Poe’s Celtic traits later on.

Poe, like [William Gilmore] Simms, was quite aware that the Massachusetts way was not his way. For him, Boston became the symbol of all that had gone wrong with American life and letters. Poe felt this was so dangerously sad because he knew that Boston had become the center of publishing and literary endeavor. He saw the place as self-congratulating, petty, parochial, and pompous. Its literary men protected and puffed themselves in all venues, including Boston’s North American Review, that very influential periodical. Poe called the periodical “the Down East Review.” He never used the term North American Review, emphasizing its “local and petty provincialism,” as he would say. For Poe, who had a broad view of art, art did not develop as the Puritan way had it. The Puritan way was to magnify one’s own virtues at the expense of “the other.” We were talking about “the other” last night [and learned that] “the other” was “outside the pale.” So, we use that Irish term again, “outside the pale.” Poe, like his own Irish ancestors, had definitely been cast outside the pale. Poe was the ultimate outsider in our literary history.

After Rufus Griswold wrote the first biography of Poe a year after his death, he was vilified as a monster. That’s where it starts, it starts with the Rufus Griswold, kind of, “vulture biography,” I guess. The Reverend Mr. Griswold, a strict New England Calvinist who became a Baptist preacher, accused Poe of having no moral sense. He imposed upon Poe his own pious Puritan literary taste. According to Jeffrey Meyers’s 1992 biography: “Griswold employed lies, plagiarism, and forgery to denigrate Poe. He forged many of Poe’s letters. Griswold concluded by thoroughly condemning Poe’s character, declaring that ‘he exhibits scarcely any virtue in either his life or his writings.’” Griswold doctored the letters, put notes in, took notes out, that sort of thing. And then he said that these sicky characters, these deranged characters in the fiction were autobiographical. So, anything these characters did, Poe did. Sleeping with corpses, that sort of thing. Griswold declared Poe had: “No moral sense and that nowhere in the literature of our language was there less recognition or manifestation of conscience.” It was the Reverend Griswold who maliciously claimed that Poe had been expelled from the University of Virginia (which he was not), that he deserted from the army (which he hadn’t), that he was addicted to drugs (which he wasn’t), that he tried to seduce his stepmother (which he didn’t). Griswold exaggerated his drinking problem and fabricated monstrous behavior for him.

Now, Poe had a drinking problem, but Meyers, I think being very astute, working with doctors who have read The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym, in which the main character, (like so many main characters in Poe) has this tremendous thirst and then passes out, and that is the perfect description of symptoms for diabetes or hypoglycemia. So, it said now that Poe probably died in a coma or a hypoglycemic coma, and that explains why he couldn’t take the people who said: “He just can’t hold his liquor. He’ll drink one drink, and then pass out.” Well, what you do is drink one drink and the sugar content is so devastating to your condition that you go into a coma. So, that’s what Meyers says. I recommend the 1992 biography. It’s just called Edgar Allen Poe. It’s a big, thick, good book.

This Griswold business was partly the revenge of a hurt ego. Poe had committed the Cardinal sin of speaking truth about Griswold’s publications, and Boston puffery that puffed it. Those with inflated opinions of themselves would get even, and so they did. The Boston literati dismissed Poe as insignificant. When William Dean Howells (I call him “that ultra-Yankee hater of the South”), told [Ralph Waldo] Emerson he was ashamed he’d enjoyed Poe as a boy, Emerson replied: “Oh, you mean that jingle man?” And that’s where the phrase, “the jingle man” comes from. Emerson called Poe, “the jingle man,” [and thereby] disparaged all of Poe’s poetry as jingles. And, of course, Poe uses that close rhyme and incessant rhyme and rhythm. That’s his trademark. Bostonian James Russell Lowell called him “juvenile.” Lowell felt Poe didn’t rise to moral maturity and wasn’t worth a grown man’s time. Lowell made the kind of sanctimonious moral judgment that Poe felt Bostonians always did. Lowell wrote a friend: “Poe is wholly lacking in the element of manhood, which for want of a better name, we call character.” In his A Fable for Critics, Lowell says that Poe is “two fifths fudge.” Lowell berates him for criticizing Lowell’s Harvard professor and friend, [Henry Wadsworth] Longfellow, and makes fun of his prosody (again, Emerson’s “jingle man”). Lowell’s greatest censure of Poe, however, was that he ignored the moral element in poetry. And this is going to be a key point I’m trying to make.

Walt Whitman, taking the nod from Lowell, said: “Poe did not have the first sign of moral principle.” Whitman criticized the lack of didactic elements in his work. Later, Bostonian Henry James also fell into the same critical rut. James wrote that Poe’s recent fame in Europe, “always puzzles me.” He felt that Poe has “no permanent literary value of any kind.” In a single word, he considered Poe “vulgar.” (Of course, James considered everybody vulgar, I expect, except the English. You know, he expatriated to Rye on the south coast of England and died there.[1] Again, “the priggishness of Boston,” Poe would say.) James felt that Poe had sacrificed moral content for terrifying effect because he was not a moral writer. He was “an embarrassment to American letters” and was thus best dismissed and forgotten. So, we come to the core of Poe’s war with Boston and its Puritan legacy. Bostonians chief dislike of Poe, as they themselves expressed it, was that his writing lacked a moral sense Poe’s writing did not preach or teach a lesson to live your life by. Poe would have quickly agreed. Sure, it doesn’t, and that’s the point. Writing should not preach or teach, for literature should not be didactic. And so, we get to the word didactic again. Poe disliked the Boston writers for doing just that: Subordinating literature to a moral lesson. Worse, the Bostonian put the moral lesson overtly on the surface, complete with moral tags tacked onto the ends of poems lest the reader miss the point. Emerson, [John Greenleaf] Whittier, Longfellow, [William Ellery] Channing, [William Cullen] Bryant, all were masters of the moral tag. They’re all didactic poets.

At the Boston Lyceum in 1845, Simms defended Poe from the attacks made by the Bostonians. Simms wrote that Boston required, “moral or patriotic commonplaces in rhyming heroics.” Simms continues: “You must not pitch your flight higher than the penny-whistle elevation. Your song must be such as they can read running and comprehend while munching peanuts.” Very practical people, these Puritans. It must be superficial. Superficial literature for people on the go. After all, remember, they have to be very busy playing God, and you gotta be really eternally vigilant. It all went back to their Puritan heritage. I think the settlers of Plymouth mistrusted, in fact, outlawed fiction in poetry. We know Cotton Mather understood fiction as lies. Fiction equals lies. Poetry, unless it was spiritually meditative, should not be allowed inside a house. The Puritans of London in Shakespeare’s day outlawed theaters. They felt certain plagues and fires in the city were God’s judgement on them for allowing the immorality of plays. That’s why the Globe Theatre, where Shakespeare’s plays were performed, had to be built on the far side of the Thames, outside the city’s Puritan jurisdiction, which I always call “outside the Puritan pale.” That’s always where the interesting things go on, you know, it’s not within the charmed campfire or at the charmed campfire within the circle of the drawn wagons, it’s out there with those wild Irish Indians. That’s where the good stuff’s going on, outside the circled wagons.

This Puritan distrust of literature put the Puritan descendant who wanted to write – can you imagine the dilemma? You’re put on the defensive! You mistrust literature anyway, you’re having to make a case for it and so you say, “Well, it can preach moral lessons.” If literature could teach more lessons, then it wasn’t sinful and writing could be respectable. And there’s a key word, “respectable.” Those people who aren’t respectable wear scarlet “A’s,” remember. Outside the pale, she’s [Hester Prynne] put outside on the edge of the woods, shunned. These are the direct roots of didacticism, then. They grow out of the Puritan ban on poetry as the Puritan banned song, dance, drink, musical instruments, plays, and card playing. Remember that business about the harp? That really would be the musical instrument you would not be allowed because it had other things built into it.

Now, let’s hear what Poe had to say about poetry. This is the antithesis, the different way of looking at literature, the different way of looking at art, which is Simms’s way of looking at art:

“There is a heresy too palpably false to be long tolerated, but one which may be said to have accomplished more in the corruption of our poetical literature than all its other enemies combined. I allude to the heresy of the didactic. Every poem, it is said, should inculcate a moral, and by this moral is the poetic merit of the work to be adjudged. We Americans especially have patronized this happy idea, and we Bostonians very especially have developed it in full. We have taken it into our heads that to write a poem simply for the poem’s sake would be to confess ourselves radically wanting in the true poetic dignity.”

Simply for the poem’s sake, “a poem simply for the poem’s sake.” Poe goes on to say that, on the contrary, there’s nothing more dignified or supremely noble, “than this very poem. This poem per se, this poem which is a poem and nothing more, this poem written solely for the poem’s sake.” In other words, the poem doesn’t have to make excuses for its existence by masquerading as a sermon. And Poe goes on to give an example of such a non-didactic poem from Baltimore poet Edward Coote Pinkney, [who was] quite a fine poet. Poe writes:

“It was the misfortune of Mr. Pinkney to have been born too far South. Had he been a New Englander it is probable that he would have been ranked as the first of American lyrists by that magnanimous cabal which has so long controlled the destinies of American letters in conducting the thing called the North American Review.”

Interestingly for the Celtic thesis, Poe goes on to cite two examples from Thomas Moore’s Irish Melodies as among the best poems in the language. Poems that are sung, not read, and having no hint of the didactic. Poe’s pure poetry concept was later adapted by the “art for art’s sake” aesthetes of late 19th-century Europe, writers who had finally freed themselves of the Puritan’s distrust of literature as inherently evil. Art for art’s sake, a poem for the poem’s sake. Even Poe’s words are being mirrored! In Poe’s defense of Pinkney, he also names another complaint against Boston and New England: They recognized no writer outside the charmed circle of their own little world. Poe’s humorous word for Boston writers was “the Frog-Pondians.” I always liked that. He just gives this wonderful image of all these frogs croaking in the little pond and nobody listening except the other frogs. Their little frog pond where they croaked was insular and provincial in the extreme. Simms had similar things to say about the Frog-Pondians. He complained that there was an essential injustice in their saying theirs was the American literature while yours is the regional one. He says it’s “very unfair for the Bostonians to say ours is the American literature, but yours is the original one.” This makes so much sense of Simms. Things come together now so much better. I kind of understood, but now we’ve got a proper broader context to put that comment in, complete with the quotations from the people Poe and Simms must have read to come up with these comments. Poe and Simms fought this cultural imperialism together. They understood the New England move to hijack the term American and appropriate it to themselves alone.

George Bancroft, a historian from Massachusetts was doing the same in writing American history. For Bancroft, the South played no real role in the [American] Revolution. It was all about the Boston Tea Party and Bunker Hill. That really got Simms’s Celtic hackles up, knowing, of course, his own family background and the background of the Irish in Charleston. In his review of Lowell’s A Fable for Critics, Simms says: “It is the misfortune of our fabler that he adopts implicitly the vulgar parochial selfishness which disfigures so greatly the popular judgements of New England.” He feels that Lowell has slighted [James Fenimore] Cooper and that Cooper is worth all the pretentious literature of all of New England. Simms proceeds to call Emerson “half-witted” and [a man] “whose chief excellence consists of mystifying the simple and disguising commonplaces in allegory, Chief of the Frog-Pondians.” The Frog-Pondians, with Emerson as the lead croaker of didactic poems and moral essays, resented hearing such. They didn’t want to hear that, didn’t want that in print. With Cromwellian zeal, they went to war against Poe and Simms, those writers outside the pale. In that defense of Poe, Simms says how interesting it is to see the descendants of the Puritans brandishing their tomahawks about Poe’s head. The Frog-Pondians’ chief weapon, then, in all of this (and it still is), is to ignore all the writers outside the closed circle. Don’t even mention them because a mention brings their name forward. The way to kill a writer is not to read a writer.

Closely related to Poe’s dislike of Frog-Pondians and didacticism was his disdain for Yankee allegory. In fiction, as in poetry, he felt that the writer should not put his message on the surface. I’m reminded of Eudora Welty in an essay called Why the Writer Should not Crusade: “The writer who crusades sells his birthright for a pot of message.” That’s good. Isn’t it? That sounds like Poe, too. Poe used John Bunyan’s The Pilgrim’s Progress as such a flawed work, a book in which the allegory is the chief aim. Poe calls it that “ludicrously overrated work.” Interestingly, Pilgrim’s Progress is the most famous Puritan work of fiction. In reviewing Nathaniel Hawthorne, Poe relates the allegory of Pilgrim’s Progress to the method of Hawthorne’s fiction. He comes naturally by it; Hawthorne comes naturally by that allegorical mode. Young Goodman Brown comes right out of the Puritan tradition of Pilgrim’s Progress. Poe’s primary critique of the Massachusetts author is that he is “infinitely too fond of allegory.”

What Poe demanded in fiction and that which he himself practiced was a “very profound undercurrent of meaning. So as never to interfere with the upper one.” There’s meaning but it shouldn’t be on the surface. In his essay The Philosophy of Composition, Poe writes that all good literature requires two things. First, some amount of complexity, “and secondly, some amount of suggestiveness, some undercurrent, however indefinite of meaning…It is the excess of the suggested meaning it is the rendering this the upper instead of the under-current of the theme, which turns into prose (and that of the very flattest kind) the so-called poetry of the so-called transcendentalists.”

On several occasions Poe singled out Paradise Lost as an overrated non-poem. In Paradise Lost, he says, “platitude follows platitude until the poem exasperates.” I’ve had that same feeling. Poe says that half of Paradise Lost is “merely a series of minor poems. And the other half is prose holding the minor poems together.” Poe thus makes Paradise Lost, which is the most celebrated of all Puritan poems, an example of what not to do in poetry. He makes Pilgrim’s Progress, the most celebrated work of Puritan fiction an overrated work, ill conceived. You can see where I’m going with that. I’m not even going to insult your intelligence by drawing the conclusion for you.

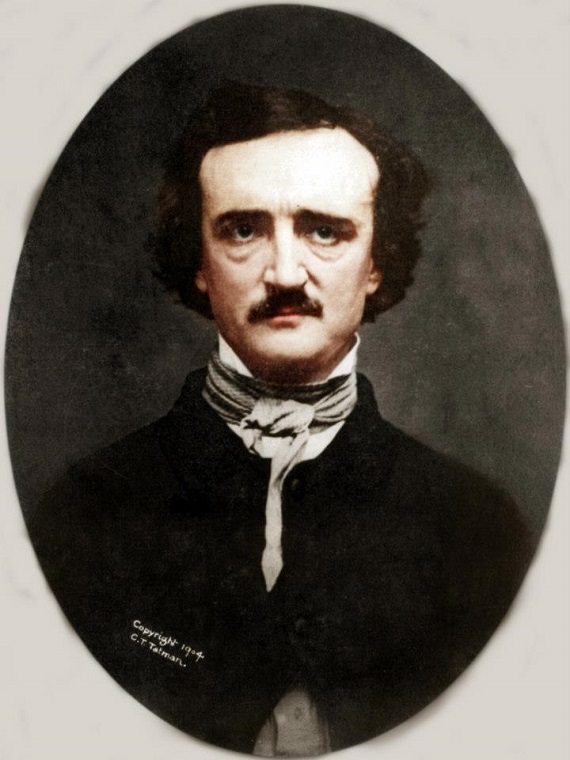

I would pose, then, that these attitudes would come naturally to Poe [who was] temperamentally unlike “those people,” (using Lee), “those people,” and antipathetic to the Puritan way of doing anything. So, it’s the culture war we saw Simms waging once again, and we’re kind of converging here. Much should be said of Poe’s Southern-ness and his being a Southern writer; that hasn’t been done. A book could be written on the subject. Included in that volume should be the Celtic nature that he and the South shared in common. You wouldn’t want to make that the central thesis, but you’d certainly want to include it. My new way of looking at Poe, that I’ve developed just in the last year, is that he belongs to the bardic tradition which still influences the poetry of Ireland. He, like Simms, spoke his poems. Simms was so remarkable. He’d just start rattling it off and go for hours, and there’d be no manuscript. Poe appeared before Susan Talley’s group of admirers “without manuscript.” She tells us: “He chants his verse and mesmerizes the gathering. He mates poetry to song.”

Poe’s incessant rhythm is indeed chant-like, a bard-like incantatory verse that holds us spell-bound. That’s a whole idea. His mysticism is bardic as well. At times, he and his narrators have much in common with the Gaelic “gealt,” that is the inspired one, frenzied with vision, in tune with the world beyond this one, the world of “supernal beauty,” as he calls it. Sometimes this frenzy, as with the gealt, takes the possessor to of the point of madness. That’s the gealt as bardic visionary.

I brought [William Butler] Yeats with me. Not a book. Yeats. This is the only recording we have of Yeats’s voice. He was recorded, but the Blitz got him. His tapes were destroyed in the Blitz, but we have this remnant of Yates reading The Lake Isle of Innisfree:

“I am going to begin with a poem of mine called The Lake Isle of Innisfree, because if you know anything about me, you will expect me to begin with it. It is the only poem of mine which is very widely known. I will arise and go now, and go to Innisfree, And a small cabin build there, of clay and wattles made; Nine bean-rows will I have there, a hive for the honey-bee, And live alone in the bee-loud glade. And I shall have some peace there, for peace comes dropping slow, Dropping from the veils of the morning to where the cricket sings; There midnight’s all a glimmer, and noon a purple glow, And evening full of the linnet’s wings. I will arise and go now, for always night and day I hear lake water lapping with low sounds by the shore; While I stand on the roadway, or on the pavements grey, I hear it in the deep heart’s core.”

This is Richard Harris. I want you to hear Under Ben Bulben:

“Under bare Ben Bulben’s head In Drumcliff churchyard Yeats is laid, An ancestor was rector there Long years ago; a church stands near, By the road an ancient Cross. No marble, no conventional phrase, On limestone quarried near the spot By his command these words are cut: Cast a cold eye On life, on death. Horseman, pass by!”

I like Richard Harris’s rendition of Yeats’s poem. Those words are carved on Yeats’s [grave] marker. The reason I brought Yeats here? You heard the incantatory rhythm. He liked Poe a lot. He would not have to be indebted to Poe for that incantatory rhythm because it comes by virtue of his Celtic understanding of what poetry should do. Yates was a great visionary. Yeats was the great poet in the English language in the 20th century. They share affinities, Poe and Yeats, and I think that needs to be talked about, written about.

As bardic visionary Poe’s taking up arms against the center of Puritan influence in America would come quite naturally, and Poe resisted the Frog-Pondians to the end. He was the good Irish Cú Chulainn, strapping himself to a standing stone fighting with his sword the waves of the incoming tide. And he saw himself as the ultimate outsider and also the man who’s not going gentle into that good night. In his 1845 essay in the Broadway Journal, Poe concludes that he couldn’t care less what the Frog-Pondians think of him. He says: “Fact is, we despise them and defy them, the transcendental vagabonds, and they may all go to Hell together!”

In October, 1849, the month of Poe’s death, Simms took up Poe’s fallen sword and made insightful pronouncement on their Boston enemies. Simms’s essay cuts to the real heart of the culture wars in which the two Southern authors had been engaged. Socinian is one who denies the Divinity of Christ and the afterlife, he explains evil rationally. According to Simms, Theodore Parker, the Boston preacher, is:

“Too Socinian for the Socinians, Parker has beaten them at their own weapons, and where they teach to believe little, he teaches them to believe nothing at all. We have long been prepared to believe that Boston would come to this. They have a school of teachers possessing large popularity and large salaries, intense self-esteem and considerable ingenuity, who with new ‘isms’ and ‘ologies’ daily will someday contrive to throw down all their altars of belief. Were they a more inflammable race, we might look for the advent among them of a goddess of Reason and a reign of Terror, not imperfectly modeled upon those of the French. Their safety lies in the fact that they are already in possession of too-large a share of worldly goods to venture much in dangerous experiments. Were they sans culottes we should very soon behold a Temple of Reason in Boston usurping that of Jesus Christ.”

Simms ends this essay with Lowell’s passage in A Fable for Critics celebrating Massachusetts. Lowell writes of the Bay State:

“Who is it that dares call thee peddler, a soul wrapped in bank notes and shares? It is false. She’s a poet. I see as I ride along the far railroad, the steam snake glide white, the cataract throb of her mill-hearts. I hear the swift strokes of trip hammers weary my ear. Sledges ring upon anvils. Through logs the saw screams, blocks swing up to their place, beadles drive home their beams. It is songs such as these that she croons to the din of her fast-flying shuttles year-out and year-in.”

Simms concludes by questioning the way of life the north is chosen. He smiles at the shortsightedness that would place industrial and urban progress over the good life. He says: “If Boston’s claims to poetry are to be founded upon her sledge and trip hammers, her mills and machinery, she may grind verses to all eternity, but he hopes she will set no one’s teeth on edge with them but her own.”

Typical southerner. Typical Celt. You do it your way, but leave us alone to do it our way. Live and let live. All we want is to be left alone, and if you choose to be wrongheaded, then that’s your right. That’s Simms. And if they’d left Poe alone, he might have said the same. Two decades after Simms wrote these words, he came to understand that sledge hammers, mills, and machinery would triumph in the culture war he and Poe had fought. New England’s literature would be forced upon the children of the conquered South. New England’s version of history would be taught in Southern schools. Emerson finally got his way. Machinery and mills would triumph, at least for a time, until the misguided understood the real loss with the victory of the machine culture and an empiricist materialistic utilitarian view of the world. In this hedonistic way of life, only the hollow shell would remain under the glitz, hype, and sham show of fashionable life. Simms made it perfectly clear where he stood in the culture war in an essay of 1841 entitled The Ages of Gold and Iron. He contrasts the ages of gold and iron. It’s little known, but it’s certainly one of the finest essays of its time:

“The golden age is the age of agricultural imminence. The nation whose sons shrink from the culture of its fields will wither for long ages under the imperial sway of iron. It may put on a face of brass, but its legs will be made of clay. It may hide its lean cheeks and all external signs of misery under the harlotry of art, but the rottenness of death will be all the while reveling upon its vitals and a poisonous breath will go forth from its decay which will spread its loathsome taint along the shores of other and happier and unsuspecting nations.”

Simms was a real visionary like Yeats. His poetry has visionary moments; his essays certainly are visionary. He sees the future. He’s wrong about those mills and, and machines. He thinks they will come to nothing. But maybe in the long run he was right. They certainly have come to a whole lot, impacting our world. To summarize what that wonderful passage means to me, I’ll put in in my words: “Imperial iron will be a plague on the world.” I believe no truer words about the culture war, North and South, have been penned by anybody. As father(s) of Southern literature, Poe and Simms knew who they were and who they were not. Thank you so much.

[1]Rye being a town in East Sussex.

This was an absolutely outstanding essay. Re Simms’ Ages of Gold and Iron, I believe Du Bois wished to make the same point in his Of the Wings of Atalanta. I certainly concur with Simms’ thesis. What a culture we have wrought. As for me, I’m off to read the Timrod I just received in the mail. And Baudelaire’s Poe!