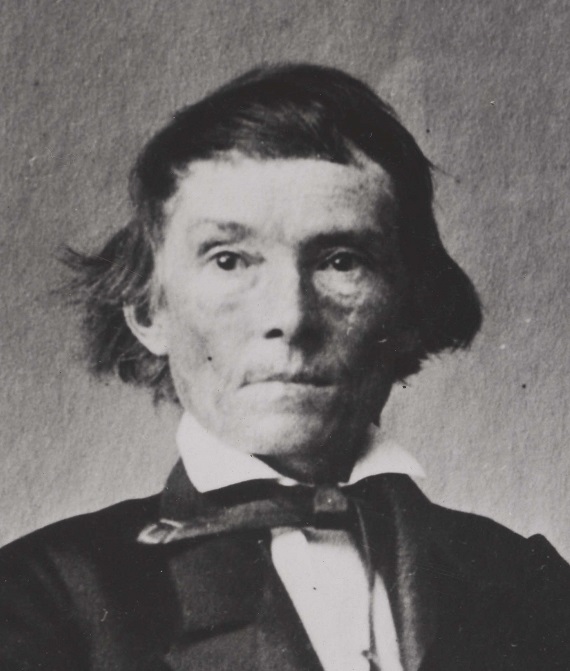

Limited by a popular and academic culture at the beginning of the 21st century that denigrates the past and places too much confidence in the present, the thoughtful student of Georgia politics and history should not be surprised that Alexander Stephens (February 11, 1812-March 4, 1883), Confederate Vice-President and American statesman, has often been neglected. One possible remedy to the neglect is to reconsider the statesman’s life and work.

Stephens was named for his grandfather, Alexander Stephens, a native of Scotland and veteran of the revolutionary war who settled in Georgia in the early 1790s. As the only child of the elder Alexander to remain in Georgia, Andrew Stephens was a successful farmer and educator. He married Margaret Grier in 1806. Within months of Stephens’ birth in 1812, his mother died as the result of pneumonia. His father quickly remarried Matilda Lindsey, a daughter of a local war hero. Matilda would exert great influence upon her stepson’s life, but the greatest inspiration to the young “Aleck” was his father. While not exhibiting any initial fondness for academic study, by 1824 Alexander was consumed with an interest in biblical narrative and history, and he began to read widely. In 1826, his mentor and teacher, Andrew Stephens, died from pneumonia; the stepmother soon died from the same affliction. Alexander was overcome by his grief, and he became disconsolate and fell into a state of melancholy. The siblings were divided, with Alexander and his brother Aaron moving in with their uncle Aaron Grier. While living with his uncle, Alexander was befriended by two Presbyterian ministers, Reverend Williams and Reverend Alexander Hamilton Webster, and these men would greatly aid his personal and intellectual development. Out of Alexander’s respect and devotion to Rev. Webster, he would eventually change his middle name to Hamilton. As the result of the encouragement offered by the clerics and others, the young Alexander entered Franklin College, which would become the University of Georgia. At Franklin, Stephens was guided in his studies by the eminent educationist, Reverend Moses Waddel, the brother-in-law and teacher of John C. Calhoun, and many of the emerging leaders of South Carolina. Waddel also played an important role in the spiritual development of the young man.

Graduating first in his class at Franklin in 1832, he had distinguished himself as a scholar and capable debater. Stephens accepted a position as a tutor and began an independent study of the law. After passing the bar examination, Stephens was elected to the state legislature; he would spend six years in the state house and senate. It was becoming apparent that Stephens possessed the qualities necessary for political success.

Initially refusing the request to run for the U. S. House, his political coalition merged with the Whig Party, and he decided to run for Congress in 1843. As a candidate, he defended the Whig Party’s positions on the national bank and tariffs. In a wave of Whig political success in Georgia, Stephens was elected to Congress, although sorrow would soon replace his joy. Within a brief period after his election, he received news that his brother Aaron had died. Stephens was again stricken with a profound sense of loss. After arriving in Washington to assume his seat, he was so sick that he was unable to attend legislative sessions. On February 9, 1844, in his first speech as a member of Congress, he challenged his own election. Stephens would become a Whig stalwart, campaigning for various Whig candidates and related causes, including Henry Clay’s unsuccessful presidential bid in 1844. The major issue before Congress was the annexation of Texas. In opposition to many southern congressmen who viewed the annexation of Texas as essential to the preservation of a political equilibrium that protected slavery, Stephens opposed expansion. Eventually, Stephens was forced to see the benefits of annexation for the South and the Whig Party, but he opposed the measure if based solely on the extension of slavery.

Troubled by President Polk’s “bad management,” including greater tensions with England regarding Oregon, and the situation with Mexico, Stephens became an outspoken critic of the administration. Polk ordered General Zachary Taylor to the Rio Grande and a conflict transpired, prompting Polk to state that a war had been initiated. While Congress provided a declaration of war, Stephens agreed with Calhoun that the war could escalate into a greater conflict. In conjunction with other Whigs, Stephens tried to limit his support of the war and to prevent Congress from acquiring territory as the spoils of the contest. He introduced legislation aimed at limiting the aggrandizing policies of the Polk administration. By 1847 Stephens had become a central figure in the Young Indians Club, a group of congressmen who were supporting the presidential candidacy of General Zachary Taylor, who he believed shared the worldview of southern Whigs.

After Taylor’s election, Stephens was forced to reconsider his support of Old Zack. Stephens found the doctrine of popular sovereignty more palatable because it was a countervailing force against the northern Whigs who wanted to admit California and New Mexico as free states. Working with his fellow Georgian and friend, Robert Toombs, they challenged their Whig colleagues to adopt resolutions forbidding Congress from ending the slave trade in the territories, but the effort failed. Within a short period of time, Stephens had moved from being a valued supporter of the administration to a critic and congressional opponent. He was forced to leave the Whig Party, but he maintained his legislative base of support in Georgia. In joining forces against the Whigs during a period of electoral realignment, he would assist in the formation of the Constitutional Union Party in Georgia.

In the midst of the turmoil, Stephens eventually joined the Democratic Party; he supported the Compromise of 1850 and was instrumental in the adoption of the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854. Stephens thought the acceptance of Kansas-Nebraska was the “mission” of his life, and that “his cup of ambition was full.” After unsuccessfully supporting various measures that attempted to secure the position of the South, Stephens announced that he was retiring from Congress. He was weary and tired of confronting “restless, captious, and fault-finding people.” He did not support extremist measures offered by his colleagues from the South, but remained an advocate of states’ rights nevertheless. Even as southern radicals encouraged secession after the election of Lincoln in 1860, Stephens urged restraint, pleading with his follow Georgians to evince “good judgment,” and arguing that the ascendancy of Lincoln did not merit secession. In a celebrated exchange with the new president, he reminded Lincoln that “Independent, sovereign states” had formed the union and that these states could reassert their sovereignty. When Georgia convened a convention in January 1861, Stephens voted against secession, but when secession was approved by a vote of 166-130, he was part of the committee that drafted the secession ordinance.

As the Confederacy evolved, Stephens was selected as a delegate and to many he appeared to be a good candidate for the vice presidency. He assumed an important role in the drafting of the Confederate Constitution and in other affairs, eventually accepting the vice presidency. Early in his tenure as Vice President, on March 21, 1861, he gave his politically damaging “Cornerstone” address in Savannah, where he defended slavery from a natural law perspective. President Jefferson Davis was greatly disturbed, as Stephens had shifted the basis of the political debate from states’ rights to slavery. Stephens was convinced that slavery was a necessity. The estrangement between Davis and Stephens increased, and by early 1862 the vice president was not intimately involved in the affairs of state. Accordingly, he returned to his home in Crawfordville. Pursuing actions he thought might assist in the denouement of the conflict, Stephens attempted several assignments, including a diplomatic sojourn to Washington. Returning to Richmond in December 1865, he introduced proposals to strengthen the Confederacy while presiding over the Senate.

Following the conclusion of the war, Stephens faced arrest and imprisonment at Fort Warren, Massachusetts. After his release, he would devote the remainder of his life to composing A Constitutional View of the Late War Between the States, a two-volume defense of southern constitutionalism which appeared in 1868 and 1870. According to Stephens, the foremost theoretical and practical distillation of authority and liberty was found within the American political tradition. The original system was predicated upon reserving the states’ sphere of authority. For Stephens, this original diffusion, buttressed by a prudent mode of popular rule, was the primary achievement of American politics.

Sean Busick also contributed to this essay.