This essay was originally published at The Deliberate Agrarian.

In my previous blog post I mentioned Allan C. Carlson’s soon-to-be-published book, The Natural Family Where It Belongs: New Agrarian Essays, and Generations With Vision, a ministry that is working to bring about the reformation of strong Christian families by casting a vision for the establishment of vibrant family economies. The anticipation of Allan Carlson’s new book has me thinking about the family economy as it relates to the Christian-agrarian worldview.

I feel compelled to add my 2-cents to this discussion because I care deeply about the well-being of Christian families (especially my own). I also understand the historical role that the family economy has played in God’s plan for His kingdom and His people. And I can see the industrial revolution has nearly destroyed the family as God designed it to function.

I sense that there is some confusion among many who are new to the whole concept of the family economy. I’m also concerned that Generations With Vision may be presenting a vision for the family economy that is focused almost entirely on a family business and entrepreneurship. Without embracing the full traditional essence and understanding of what a family economy once was, and must needs be again, I fear that family reformation may not succeed. I’m hoping that Allan Carlson will inject this missing agrarian aspect into the discussion with his new book.

In any event, it occurred to me that I had written something about the family economy in my 2006 book, Writings of a Deliberate Agrarian. I decided to read again what I had written. It turns out that I’ve already expressed my thoughts (most of them) on this matter, and I have decided to just publish the whole chapter. Here it is…

Returning To The Family Economy

We live in an industrial economy. Some say we are actually now in a service economy. If so, it is still a part of the industrial paradigm. In such an economy, the typical family is not a producer of goods. It is a collection of individual consumers. This is the way the industrial providers like it to be. They want everyone to be dependent on them. But that is contrary to the historical pattern. For hundreds of years prior to the industrial revolution, families were self-reliant, integrated units of efficient production. This historical model of family-based production is referred to as the family economy.

In a properly functioning family economy, every member of the family—father, mother, children, grandparents, and any extended family living under the same roof—plays a role in making the family as self-sufficient as possible. Everyone works for the good of the family. Everyone is needed.

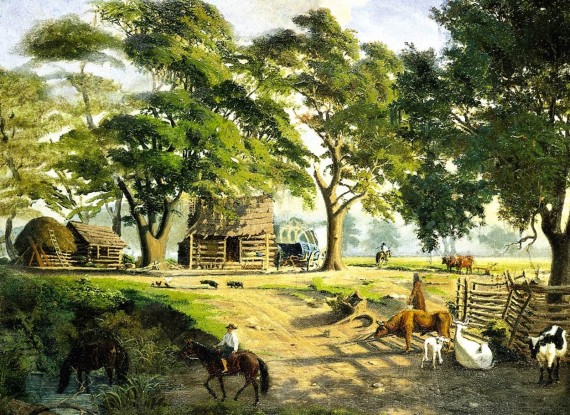

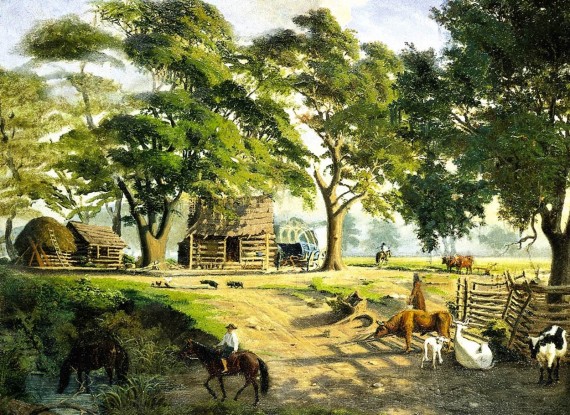

This model is naturally suited to farming and homesteading. It was the norm in agrarian America prior to the mid-1800s. Many farm families tenaciously held on to some form of this lifestyle well into the 20th century. Today it is an anachronism, but that may be changing.

The family economy has, in times past, also included numerous cottage industries. Grain milling, candlemaking, tinsmithing, blacksmithing, coopering, carriage-making, and furniture-making are just a few examples of small-scale home businesses that contributed to the economy of many families. Each of these crafts and services was performed in, or just outside, the home. Such homes would also have gardens and some livestock. Even in the villages, it was not unusual to have a family milk cow. Again, self-sufficiency and thus, survival of the family, was the collaborative objective.

Within the family economy, mothers and fathers taught their children the many different skills associated with their way of life. The whole idea was to train children to be productive members of the family as children so they would become productive, self-reliant leaders (and teachers) of their own families one day. The virtues of thrift, hard work, family closeness, and religious faith, were integral elements of these families of yore and produced men and women of great character.

The primary objective of the family economy was not to make a lot of money. It was to sustain a way of life. Indeed, most farming was subsistence farming, which means the family produced just about everything they needed, bartered for what they did not have, and did not require a lot of money.

That kind of life is hard for us to imagine these days. We figure subsistence farmers must have been poor miserable beings, barely surviving. But these were people who knew how to make the land produce and, for the most part, they operated thriving farms and homesteads. They had what they needed to live a good and full life.

It is my firmly-held belief that in order to build strong families and reestablish a vibrant agrarian culture, individual families must rediscover and deliberately work towards reuniting the entire family into some sort of family economy.

Most agrarians clearly see the blending of family life and work into a more self-sufficient family economy is the ideal. It is something they dream of and work towards. I am one of those people.

But the reality of the situation is, unless you are born into an already-established family business, or you are independently wealthy, a true and complete family economy is not easily accomplished in this modern world.

Those families living prior to the mid-1800s did not have exorbitant property taxes extorted from them to pay for government schooling schemes. There was no federal income tax to support a bloated and oppressive federal bureaucracy. Spending on social programs was minimal. Life, health, auto, property, and unemployemnt insurances were, I’m guessing, not even around (certainly not auto).

Money was the real thing—gold and silver, not the fiat currency that governments so conveniently devalue through inflation. Huge stores full of manufactured goods, which we’ve been conditioned to think we must have, were not around back then either. Children were not being bombarded with messages to continually be buying the latest whatever.

For new agrarians of the 21st century to reestablish family economies, we need to, first, get out of bondage to debt. A key part of doing this is to simplify our needs and wants; we must tame our tendency toward materialism and consumerism. Then we must endeavor to supply as many of our family’s needs as possible. And finally, we must also create family businesses that generate enough actual money to pay the most necessary of living costs in our very expensive industrial economy.

All of this is an enormous challenge. It is not something that most people can do overnight. But it is something that most people can begin on a small scale and slowly, deliberately, bring to fruition.

There are some brave and innovative pioneers who are establishing wonderful examples of godly family economies. Joel Salatin comes to mind immediately. There are many others testing the waters and paving the way. If the task were easy, more people would be doing it. Nevertheless, the goal of bringing fathers home and reuniting families in life and work is noble and necessary. The difficulty of attaining an ideal is no excuse for not pursuig it.

#####

I wrote that essay with passion and conviction back in 2005 (it was originally posted to this blog). At that time I was working to establish a home-based business that would pay the bills and allow me to leave my industrial-world job. Since then, the business has been very blessed, and I was able to come home a year ago this month. My example should be an encouragement to others who see and desire the same thing. But my quest is not entirely successful. I have not fully “arrived” at some ideal. Mine is a family economy, on the land, that is still developing. I’ll have more to say about this subject in my next essay.