This essay is taken in part from the chapter “Frontiersman” in Brion McClanahan’s The Politically Incorrect Guide to Real American Heroes (Politically Incorrect Guides) and is presented here in honor of Crockett’s birthday, August 17.

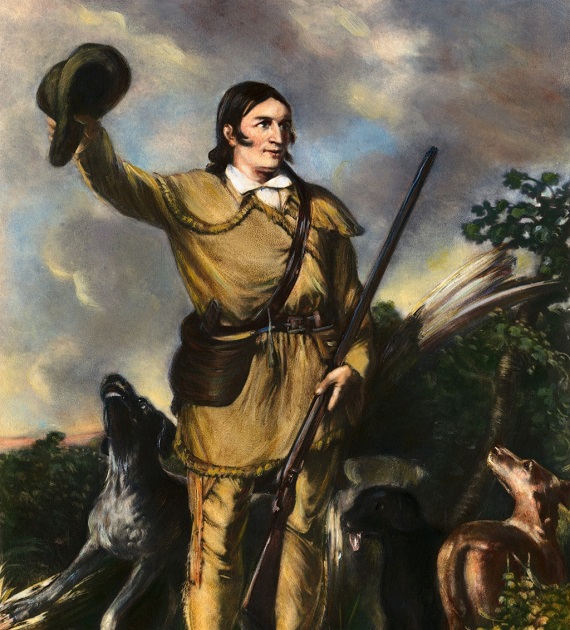

The modern actor Billy Bob Thornton once said David Crockett in the film The Alamo was his favorite role. John Wayne played him, too. Every boy who grew up before the 1970s wanted to be Crockett. He was the “king of the wild frontier,” the man who wrestled bears and jumped rivers, the man with the sharpshooter’s eye who tamed the wilderness. He was larger than life; as one historian wrote, “His life is a veritable romance, with the additional charm of unquestionable truth. It opens to the reader scenes in the lives of the lowly, and a state of semi-civilization, of which but few of them can have the faintest idea.” Crockett was so popular because he was one of us, a common man without advantages who achieved great things on his own merit. He was the quintessential American.

Crockett was born in 1786 in Hawkins County, Tennessee. His father’s family had emigrated from Ireland and settled in the expansive and untamed wilderness in the mid-eighteenth century. Their “cabin” was little more than four walls made of small logs, a bark-covered roof, and a dirt floor. They could hunt, and like many Scots and Irish who settled on the frontier, they eked out a life of subsistence–until they eventually fell under the knife of a marauding Indian tribe. Life on the frontier was not for the weak.

Crockett’s father, John Crockett, avoided the massacre because he had been hired out as a day laborer in Pennsylvania. John Crockett had served in the American War for Independence and taken part in the Battle of King’s Mountain in North Carolina. After the war was over, he married a woman from northern Maryland and settled for a time in western North Carolina. Neither had an education, and like their predecessors, they struggled to survive on the fringes of civilization. After three years, they pulled up stakes and moved to Tennessee. This was a common occurrence for the Crocketts. They seemed to move every few years, always looking for more land and a better life, free of the confines of civilization. John Crockett owned a tavern, a mill, and on several occasions tracts of land as large as 400 acres, but he was never wealthy. The family farmed and hunted but had little in the way of creature comforts. Their log cabins were simple, usually one room, with home-made furniture from local wood and animal skins, but this was the way of life on the frontier, the only life David Crockett knew.

Until he was a teenager, David Crockett never had an education. His parents were illiterate, and Crockett himself said that he didn’t see a use in books. A book could not provide food or shelter. Living was hard, and simple tasks that modern Americans take for granted, such as acquiring food, required strenuous effort. Those who lived on the frontier were a hearty, independent stock. Dangers from wildlife, hostile Indian tribes, and poor weather made the immediate more important than the future; the faster a young man could contribute to the struggle to survive, the more valuable he was to the family. David Crockett became an excellent shot because he needed the skill to survive. Marksmanship meant you could eat.

David Crockett had a difficult childhood. His parents showed him little love or tenderness. When and when he was twelve, Crockett was sent on a 400-mile cattle drive with a Dutch stranger, on foot. He had to find his own way home, traversing the unforgiving countryside often in the snow, Crockett finally made it back to his father’s tavern. He did not receive a warm welcome. After he skipped school for several days, his father threatened to beat him severely, and Crockett again left home, this time on his own accord. In a journey similar to the one he had just undertaken, Crockett made it to Baltimore, Maryland. He was only thirteen.

Crockett spent two years away from home, and after returning was forced to go to work to settle several family debts. According to the law at the time, boys were required to work for their parents and help support the family until twenty-one. Crockett did so, but at sixteen his father graciously released him from his obligations. He was already an independent man, having lived in the wilderness for three years working to provide his own subsistence. His trials as a young teenager had made Crockett a student of human nature. Though he didn’t have a lot of book knowledge, he had a quick wit and plenty of street smarts—or, more accurately in his case, wild frontier smarts.. Crockett was also able to use his skill as a marksman to acquire needed money in “shooting matches.” But he had no property, save a poor horse and had to depend on others for work. This lack of assets presented a problem for a young man looking for love.

The people in his community thought well of Crockett, but he nevertheless had trouble finding a wife. He was rejected once, jilted the day before his wedding on another occasion, and almost run off from his future bride by her mother. Modern young men scorned in love may find solace in the fact that the great Davy Crockett was once a forlorn and heart-broken lover. Once married, Crockett attempted to settle into the routine of a frontier farmer. His wife brought a small dowry with her, and as a man of his word who always paid his debts, he was afforded a small loan from a friend. Crockett was thus able to establish a homestead, but he did not have the resolve to be a farmer. Restless, he moved his young family west in search of better land and a better opportunity. Fate intervened.

Crockett fought in the Creek War of 1813–1814, insisting it was his duty to serve his country. He served as a scout early in his enlistment and took part in several small skirmishes and raid on a Creek village that forever seared into his memory the horrors of war. He returned home and settled down but his wife died one year later, leaving Crockett with three small children. He then married the widow of a soldier fallen in the Creek War, and had two more children. Crockett determined that his large family needed better pasture, so he pulled up stakes again and headed further west. As he had said around 1810, before his first relocation west, “I found I was better at increasing my family than my fortune.”

Crockett had already earned a fine reputation as a scout and riflemen by his exploits during the Creek War. Everyone trusted him, and his honesty and work ethic placed him among the first rank of the people of Tennessee. It was no surprise, then, that after settling into Giles County, he was elected first as a magistrate and then as a justice of the peace. Crockett had no legal training. He could barely read, but the people respected his commonsense approach to law and politics. To elitists in his own day, Crockett was an example of the backwardness of America. Simple men, they thought, did not belong in government. This, of course, is the same scorn that is leveled at hard-working Americans today by the self-appointed American intelligentsia. But hard-working people recognize bravery and honesty, and Crockett had plenty of both. As a result he was sent to the state legislature in 1821.

Shortly thereafter, Crockett again moved his family west, settling near the Obion River. He hunted bears, killing over 105 in less than a year, a statistic that must send P.E.T.A. into cardiac arrest. This was the happiest time of his life. Though his closest neighbor was seven miles distant, the people again sent him to the state legislature. Crockett could not escape his reputation. His independence both as a man and statesman was evident in his opposition to the election of Andrew Jackson as Senator from Tennessee in 1825. He refused to wear the collar of “Jackson’s dog.” He lost his re-election bid and spent two years dabbling in commerce. In 1826 he decided to run for a seat in the United States House of Representatives. His humorous home-spun stories won over the public, and he was elected to the Twentieth and Twenty-First Congresses (1827–1831).

Crockett quickly displayed his statesmanship. He had supported Andrew Jackson for president in 1828, but, just as in 1825, refused to blindly follow every decision Jackson made, and once explained, “I voted for Andrew Jackson because I believed he possessed certain principles, and not because his name was Andrew Jackson, or the Hero, or Old Hickory. And when he left those principles which induced me to support him, I considered myself justified in opposing him. This thing of man-worship I am a stranger to; I don’t like it; it taints every action of life; it is like a skunk getting into a house —long after he has cleared out, you smell him in every room and closet, from the cellar to the garret.” Crockett later said he “would sooner be honestly and politically [damned] than hypocritically immortalized.”

He voted against Jackson’s “Indian Bill” because he thought it immoral and unjust. The people of his district turned on him and even drew up papers charging Crockett eight dollars for every vote he missed while in Congress (this was the per diem amount congressmen were paid at the time). This money, they contended, had been swindled from the public treasury and should be returned. Crockett was defeated in his re-election bid in 1830, but won again in 1832 and spent one more session in Congress, from 1833 to 1835. On his trip back to Washington, Crockett reportedly made the following toast at a dinner party, in obvious reference to the growing power of President Jackson, “Here’s wishing the bones of tyrant kings may answer in hell; in place of gridirons, to roast the souls of Tories on.”

He took a tour of the North and received praise for his manly, independent streak at every stop, from New York to Boston. People asked to shake the hand of an honest man, to hear the stories that made Crockett famous, to soak up the atmosphere of the frontier. To Northern city-dwellers, Crockett was a curiosity. But he was American in the purest sense, cut from the rough-hewn cloth of independence and hardened by the ax and rifle. His political accountability was noteworthy. After receiving a tongue-lashing from one of his constituents for voting for a bill that was clearly unconstitutional, Crockett responded:

“Well, my friend, you hit the nail upon the head when you said I had not sense enough to understand the Constitution. I intended to be guided by it, and thought I had studied it fully. I have heard many speeches in Congress, but what you have said at your plow has got more hard, sound sense in it than all the fine speeches I have ever heard. If I had ever taken the view of it that you have, I would have put my head into the fire before I would have given that vote; and if you will forgive me and vote for me again, if I ever vote for another unconstitutional law I wish I may be shot.”

While Crockett was famous during his lifetime, his greatest glory would be his last.

Crockett lost his re-election bid in 1834. Crowds greeted him at every stop on his return trip to Tennessee, but hunting and the woods did not have the same appeal as parties and stump speeches. Crockett had been civilized, and perhaps wanted to be president. Crockett famously and bitterly told his constituents that “they might all go to hell, and I would go to Texas.” Thus the die was cast. If the United States would not have him, then perhaps Texas would. He left his wife and children behind and set off for Texas in 1835, just months after returning from Washington.

This last adventure included hunting buffalo on the prairie, sharpshooting contests, almost dying after a cougar attack, and enjoying the exotic territory west of the Mississippi. He arrived at the Alamo in February 1836, just days before Santa Anna determined to lay siege to the fort surrounding the mission. This battle would make him more famous than ever—forever a hero.

Crockett understood that the way a man died often defined his life. When the Mexican army began their assault on the Alamo in late February, Crockett and the 150 or so men who manned the fort held off their foes (perhaps as many as 3,000) for several days with superior marksmanship. Crockett himself reportedly killed over twenty men. He wrote in his final journal entry dated 5 March 1836, “Liberty and Independence Forever!” The next day, the Mexican army over-ran the American contingent and slaughtered every man there. Crockett reportedly fought bravely and died well, perhaps as one of the last men to meet his fate. “Remember the Alamo!” has since been recognized as a rallying cry for all Americans. Crockett died as he lived, bravely and manfully fighting for principle and independence.