A review of Original Intent and the Framers of the Constitution by Harry Jafffa, (Regnery, 1994).

When Professor Harry Jaffa, in his new book Original Intent and the Framers of the Constitution: A Disputed Question, refers to Abraham Lincoln as the “greatest interpreter of the Founding Fathers,” one must wonder whose Founding Fathers he has in mind. From the outset of his work, Professor Jaffa renders a version of history that places Lincoln, Madi¬on and Jefferson on one side while “Calhoun and Marx stand upon identical theoretical ground” on the other side.

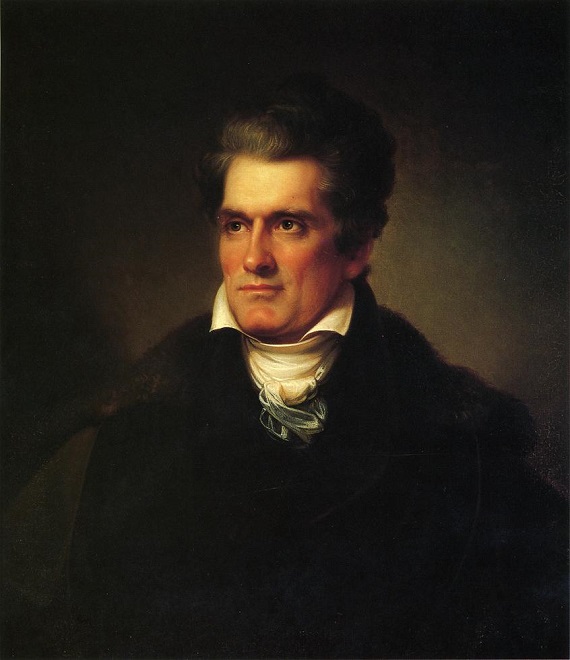

Professor Jaffa, a former speechwriter for Barry Goldwater and disciple of natural-right proponent Leo Strauss, attempts to prove that the “self-evident truths” found in the Declaration of Independence take precedence over the text and compromises of the Constitution. Using what John Randolph called “metaphysical madness,” Professor Jaffa spends much of his book attacking the views of modern conservative legal theorists such as Judge Robert Bork and Chief Justice William Rehnquist. Professor Jaffa laments that the “chief intellectual progenitor” of these “self-styled conservatives” is not “the father of the Constitution, James Madison . . . but John C. Calhoun.” Professor Jaffa describes Rehnquist as a man who “seems to think . . . Nazi or Bolshevik or (cannibal) law would result in the same ‘generalized moral rightness or goodness’ as the law of a constitutional democracy.” Because Rehnquist refuses to write his own opinions into law insofar as he adheres to precedent and the text of the Constitution, he is derided as a “moral skeptic” and a “legal positivist.”

Professor Jaffa uses the phrase “the good people of these colonies,” found in the Declaration, to launch his attack and fashion the signing of the Declaration as the “fundamental act of Union” among the several states. Professor Jaffa concludes that Lincoln comprehended this and thus based his aggression against the Confederacy on the “laws of nature and nature’s God.” Using this logic, Abraham Lincoln’s war against the South was a fight for the natural rights of man—not an attack on sovereign states that had withdrawn their consent to be governed. To Professor Jaffa, the original intent of the framers of the Constitution can only be understood vis-a-vis the natural law found in the Declaration.

In order to connect the founders with his theory, Professor Jaffa cites correspondence between Jefferson and Madison in which they recommend to the law faculty of the University of Virginia the Declaration as the “first of the ‘best guides’ to the principles of governments, of both Virginia and of the United States.” Upon this correspondence, Jaffa builds the majority of his argument concerning the centrality of the Declaration in American jurisprudence. Strangely, Professor Jaffa fails to mention the Articles of Confederation, which became operable just five years after the Declaration was signed, and the fact that under this document each state retained “its sovereignty, freedom, and independence.”

Though Jaffa fondly quotes Madison and Jefferson’s advice to law faculty of the University of Virginia, he ignores their more formal statements and writings. For instance, when Patrick Henry, during the debate over ratification of the new Constitution in Virginia’s great Convention of 1788, questioned Madison as to why the Preamble read “We the People” rather than “We the States,” Madison replied that the people alluded to were not “the people as composing one great body,” but instead “the people composing thirteen sovereignties.”

Professor Jaffa conveniently ignores the Kentucky Resolution (penned by Jefferson) and “Mr. Madison’s Report” to the Virginia General Assembly, both of which recognized the sovereignty of the states and their “duty” to “interpose” against the transgressions of the general government.

The Founders of the Republic and the Confederacy understood this idea of states’ rights. It was not the invention of John C. Calhoun as Professor Jaffa contends. In Professor Jaffa’s rendition of history, the cornerstone of the Confederacy was “the newly discovered scientific truth of Negro inferiority,” not limited government of a federal character.

Amazingly, Jaffa ranks Alexander Stephens, the Vice-President of the Confederate States of America, with the two greatest despots of the twentieth century—Adolph Hitler and Josef Stalin. “Hitler, or Stalin, or Stephens, must be refuted,” writes Professor Jaffa. And the only way “the actions of Hitler and Stalin and Stephens can be proved wrong” is to look to the Declaration of Independence. Stephens’ A Constitutional View of the Late War, which has been called the best statement of the Southern position by such noted historians as Clarence B. Carson, is not mentioned in Professor Jaffa’s critique.

Not only does Professor Jaffa compare Stephens with Hitler and Calhoun with Marx, but he sets his sights on Russell Kirk as well. Kirk is criticized for “pursuing the path of John C. Calhoun” in asserting that the Declaration was “not conspicuously American in its ideas and phrases, and not even characteristically Jeffersonian.” Professor Jaffa refuses to recognize that much of what the colonists demanded was not based on “the laws of nature,” but on their rights as Englishmen. Kirk’s contention that the colonists, in part, sought to restore their rights as free Englishmen is called “sheer nonsense.” Moreover, the fact that the delegates to the Constitutional Convention of 1787 repeatedly praised the English Constitution as the best in existence carries no weight with Professor Jaffa. To him, the original intent of the Revolution and the Constitution that followed was a complete break with the traditions and institutions of the mother country.

Consistent with this anti-English sentiment, Professor Jaffa substitutes the principles of the French Revolution for the principles of the American founding era. Professor Jaffa’s statement that “The will of the people is the ground of all constitutional authority,” is strikingly similar to Jean Jacques Rousseau’s concept of the general will. According to Rousseau:

Each of us puts his person and all his power in common under the supreme direction of the general will; and in a body we receive each member as an indivisible part of the whole.

This concept of the general will, which was embodied in the Reign of Terror in France, squares with Jaffa’s theories concerning the supposed union wrought by the Declaration and Lincoln’s enforcement of the general will of the North against the South. For Professor Jaffa and the Jacobins, no written constitution or tradition can override their concepts of natural law. “What was supremely important,” writes Professor Jaffa, “was that the Union was preserved, slavery was destroyed, and the rule of law as an expression of human equality was vindicated” (italics mine). Never mind the casualties inflicted, the damage done to the federal system and property rights, or the consolidation of power in Washington. What is important to Professor Jaffa is the vindication of “human equality” found in nature’s law.

In short, Professor Jaffa errs by confusing the principles of the American Revolution and Southern secession (liberty, limited government and property rights) with the principles of the French Revolution (equality, the general will and the repudiation of tradition). Professor Jaffa does much damage to his cause insofar as he neglects many rather elementary historical facts. Nonetheless, for anyone curious as to the thought process of a Radical Republican/Jacobin, Original Intent is a must.

This review was originally published in the 3rd Quarter 1994 issue of Southern Partisan magazine.