A Review of The Resilience of Southern Identity: Why the South Still Matters in the Minds of its People, by Christopher A. Cooper and H. Gibbs Knotts, Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2017. Reviewed by Michael Potts.

Progressive ideology dominates academia, and political science is no exception. Professors Cooper and Knotts, political scientists from Western Carolina University and the College of Charleston respectively, offer a book that presents such a progressive view. This point of view taints their book with a fundamental misunderstanding of traditional Southerners. Despite providing some useful information, the book is ultimately a flawed attempt to deal with the issue of Southern identity.

Cooper and Knotts correctly point out the importance of regionalism for identity, especially in a more “globalized” world. One could argue that the current rise of both “nationalism” and regionalism is a rebellion against a perceived globalist attempt to blend people into a homogenous culture with lip service paid to a politicized notion of “diversity.” They argue that “regions” in the sense of “The South” are socially constructed entities, though including the importance of geography, food and family customs, and other social practices that change over time.

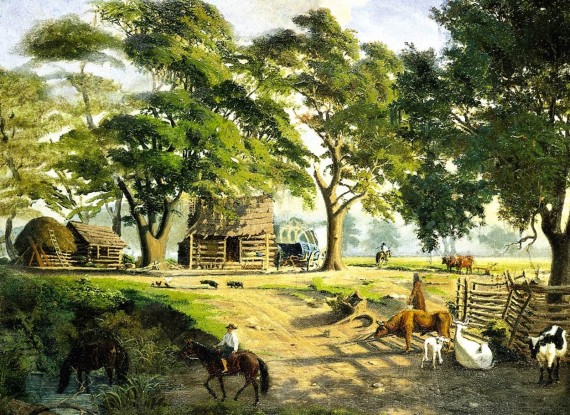

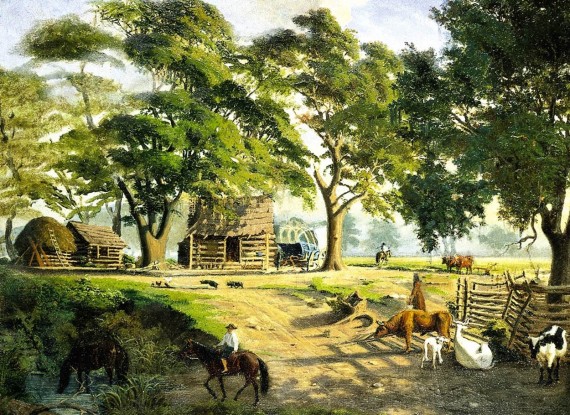

While this is true as far as it goes, a deeper issue is why human beings tend to become attached to regions. Aristotle noted long ago that “Man by nature is a political animal,” by which he means a “social animal.” With the advent of stable agricultural settlements, human beings began settling down in particular regions, and with few exceptions moving only when war, famine, or disease drove them to a new place. Loyalty to the community (and love of the region) stemmed from a continual history of family ties in a particular land. This is beautifully illustrated in Achebe’s Things Fall Apart, in which an African village is held together by family ties stretching back hundreds of years, and religious and cultural practices, especially surrounding growing yams. The South held on to a similar way of life longer than other areas of the country, and even in my own family my parents live two doors down from where my great-great grandmother lived. As with my own family, relatives tended to be concentrated in small farming communities with much commonality in religion, customs, food, and attachment to a particular place. There remain sufficient fragments of the old culture in some rural areas of the South, and as Cooper and Knotts’ survey research indicates, there is sufficient historic memory that attachment to family, the land, and tradition remains a part of at least some suburban and urban Southerners.

What their research reveals is that most Southern people view themselves as distinct—and view their being Southern in a positive way. Continuing the work of John Sheldon Reed, their findings on Southern foods confirm Reed’s conclusion that the South is distinctive. Grits, chitlins, and pork rinds are significantly more common in the South than in the North. Beyond this surface level, the authors emphasize the role of food as a unifying force in Southern communities. Their focus group discussions with both white and black southerners revealed that food was part of the culture of large family gatherings, with at least one family member known for making the “best” type of food item, such as squash casserole or sweet potato pie. They also found Southerners preferred the slower pace of life in the South vs. Northern cities. The importance of the land, especially rural land, was affirmed by the suburbanites they interviewed, which the authors found surprising.

To the authors, the most surprising finding is that most blacks in the South self-identify as Southerners, with recent polls putting the figure in the mid 70s. While one might attribute that figure to civil rights legislation, blacks most often appealed to factors such as the sense of community, politeness, the slower pace of life, and reverence for the land. I would also add the importance of Christianity in the lives of blacks, and how revivalistic, evangelical, and often Pentecostal Christianity fits well into the culture of the South. Both races share many of the same foods, and in rural areas large family gatherings are common in both groups. Blacks recognize that they are part of a common culture even though there may be some aspects of it with which they disagree.

I would have preferred to see more discussion of Southern religion. Beginning with the religious revival in the Confederate armies and as a response to the sense of hopelessness after the War between the States, a deep evangelical faith became a vibrant part of Southern culture. Yet the authors say little beyond noting that Protestantism is a predictor of perceived Southern identity, a finding that should be no surprise given the historically Protestant population of the South. One cannot separate family, culture, and tradition from religion, especially in the South. The Pew Research Center lists the South first in the categories of people who (1) believe in God, (2) believe religion is important in their lives, (3) pray frequently, (4) read scripture weekly (at 44% the percentage is 12 points higher than any other region), (5) believe in heaven, and (6) believe in hell. Although Southerners may not identify as Southern because of their greater religiosity, given the key role religion plays in Southern culture, the extent of its role in Southerners’ sense of identity should have been discussed in much more detail.

Cooper and Knotts are deeply flawed in their view of “traditional Southerners.” The “Old South” is referred to as “a South of traditional gender roles and a highly established racial order—one more defined by the Confederate flag and tales of old Dixie than by the integration of African Americas into the political leadership of the region” (5). They also affirm that the tragic 2015 Charleston church shooting was influenced by this point of view. Later, in reference to a street in Charleston named after John C. Calhoun, the authors only mention him by quoting his statement that slavery is “a positive good” (11), instead of recognizing him as a significant political thinker. In reference to what they label the “dark side of Southern identity,” they refer to the Dixicrats, George Wallace, Richard Nixon and the Republican Party’s “Southern Strategy,” “and the political use of southern symbols like the Confederate flag” (13).

One bad habit among scholars of the South is to categorize the “Old South” as a set of monolithic evil attitudes. The Old South is considered to be hopelessly racist, floundering in a “Lost Cause” mentality concerning the War between the States, with the Confederate flag symbolizing a racist past. The New South, on the other hand, is progressive on race relations, has put the “Civil War” behind it, and keeps what is good about Southern heritage, such as food and family, shirking away from the rest. Such a Manichean vision distorts the past and the present.

For example, are those who fly and admire the Confederate flag racists who want to bring blacks back to the Jim Crow era? Due to twenty years of propaganda by the NAACP and other civil rights organizations, most blacks associate the flag with Jim Crow and the Klan. There are some white southerners, sadly, who are racists and try to use the flag as a symbol of their own prejudices. However, most white Southerners (62% in Cooper and Knotts’ poll) believe the flag to be about Southern heritage and not about racism and Jim Crow. It would be unjustified to label everyone in this group a “racist.” Appeals to “ulterior motives” are speculative and lack any empirical support. Contrived experiments measuring “attitudes” after a person’s exposure to the flag do not reflect real-life situations and have limited applications to concrete situations in everyday life. If most Southerners identify the flag with “Southern heritage,” why assume a priori that by “Southern heritage” they mean slavery, racism, and Jim Crow? “Southern heritage” might mean, in the context of the flag, honor, courage, devotion to duty, to one’s God, to one’s family, to one’s land.

The authors hint that conservative politics is linked to racism, although they do not say this outright. Goldwater’s appeal to the Southern vote in 1964 and Richard Nixon’s “Southern Strategy” are considered to be racist. But why should such appeals be racist? Goldwater appealed to his belief in s small federal government that respected the rights of the states, a constant theme in Southern politics to this day. Nixon, knowing the frustration of Southerners with de facto rule by federal judges and the social engineering of forced busing, naturally took advantage of the political situation. There is no reason to label such a strategy “racist.”

Cooper and Knotts also argue that their polls reveal that political conservativism is positively correlated with affirmation of Southern identity. By “conservatism,” they apparently believe the beliefs of the current Republican Party. Of course when someone describes himself as “conservative,” that does not specify what “conservative” means. “Conservative” is said in many ways, and it would be helpful if the authors had nuanced their poll and discussion to reflect this fact. With that said, there has been a conservative bent to the South historically, and this has continued into the present. Its roots lie not only in the traditionalism that emphasizes land and kin, but also in a dislike of concentrations of power in government and business. The experience of an overarching federal government intruding on the South dates years before the War between the States (the tariff the North imposed on the South, for example). Large banks and corporations took advantage of Southerners after the war. It would probably be fair to say that corporate “big government” conservatism may not be as common in the South as in other areas of the country, but further research is needed.

The authors make two fundamental errors. First, they assume the South should be more “progressive,” and too easily identify conservativism with racism (a move all too often made by academics on the political left). Second, they fail to seek what is behind the political conservatism of the South, which is a deep cultural conservatism, a combination of traditionalism regarding religion, the family, one’s land, courtesy for others, and a distrust of entities such as government and big business who interfere with these traditional values. In this sense, conservatism does seem to be commonly connected with a sense of Southern identity.

Thus while Cooper and Knotts offer some useful information about how traditional views of home, family, devotion to land, and courtesy have continued to be associated with Southern identity, because of the negativity of the authors toward traditional Southerners, I would recommend reading this book with caution.