A review of Grant and Lee: Victorious American and Vanquished Virginian (Regnery History, 2012) by Edward Bonekemper, III.

I don’t think a person of sound mind and impartial understanding of the so-called Civil War could get past the second paragraph of the introduction of Edward H. Bonekemper III’s book Grant and Lee: Victorious American and Vanquished Virginian without realizing that next 400 or so pages were going to be an exercise in intellectual endurance.

“Because Southerners were more greatly affected by the war and had a need to rationalize its origins and results, Southern-oriented historians dominated Civil War historiography for the first centery after the war. They created the ‘Myth of the Lost Cause’ and designed Lee as the god of this mini-religion.”

Good Lord.

Southerners were more greatly affected by the war? Well, that typically happens when a country is invaded. Remember, South Carolina and her sister states of the Confederate States of America did not seek to seize control of the government of the United States. Nope. They left the United States. That’s it. They left. There would have been no bloodshed at all had Abraham Lincoln not decided that he was not bound by the U.S. Constitution — the one he swore to God to uphold — and sent soldiers to pillage and plunder the states whose people had voted to leave…peacefully.

So, when Bonekemper writes that the South needed to “rationalize” the cause and effects of the war, it would seem that by his purposefully erroneous retelling of the facts surrounding those causes and effects, that he is the one who has some need to rationalize.

That makes sense, though, in light of the facts I recited above. It’s hard to make heroes out of men who invaded other men’s homes and farms, particularly when the latter group had no intent of ever doing anything harmful to the lives, liberty, or property of the former group of men. This fact can never be repeated often enough: there would have been no war had Abraham Lincoln not violated the U.S. Constitution and ordered U.S. troops to invade South Carolina. That was an act of war. Secession was an act of peace. If you, like Bonekemper, don’t understand that, then his book is probably for you.

Now, on to the rest of this hefty hagiography of Ulysses S. Grant and the justification for Northern invasion and plunder.

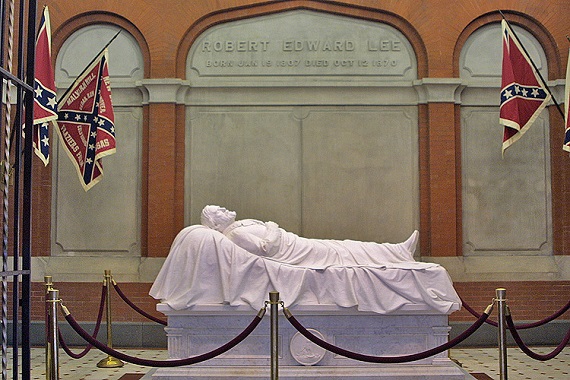

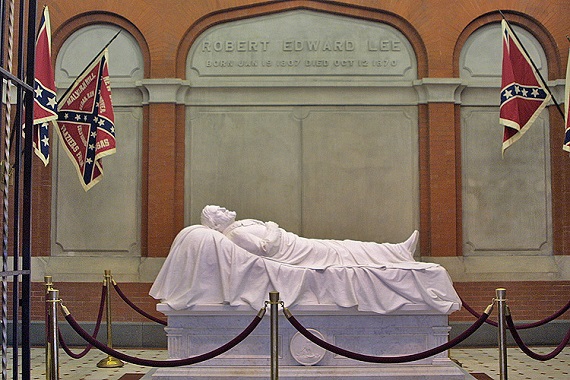

The author writes that Robert E. Lee “oversaw the slaughter, decline and surrender of his army….”

Well, I guess one could see it that way, but an intellectually honest person could see that Lee’s army would never have been “slaughter[ed]” had Abraham Lincoln not sent soldiers down to slaughter them!

Robert E. Lee would have lived a peaceful and prosperous life had he not been forced to fight for the freedom of his farm and family. He did not ride to Washington, D.C. at the head of army seeking to install himself or Jefferson Davis or any other Southern man in the White House.

Was the Southern army slaughtered? Yes, for the most part. Was Robert E. Lee the head of the Confederate army? Yes. But that is hardly the end of the story.

In the law there is a concept known as the “proximate cause.” Simply, it is the “but for” cause of an effect. In other words, what was the one thing that happened that more than any other caused a certain event to occur? Regarding the massacre of men in the Confederate army, the proximate cause was not Robert E. Lee’s abilities as a general, but it was Abraham Lincoln’s violation of the U.S. Constitution and the subsequent invasion of the South by armies of the United States, at his command.

To pen a chapter-by-chapter review of Grant and Lee would be an irresponsible redundancy. It follows the familiar script drafted in the days of Reconstruction: the North fought to free the slaves, Abraham Lincoln was the “Great Emancipator” and a martyr of liberty, Southerners were fighting to keep their slaves, and after the war, the South remained racist despite the dedicated and enlightened efforts of the virtuous and victorious North.

Rubbish.

Before beginning the denouement of the review, I will mention one statement made by Bonekemper that begs for a correction.

Speaking of the Emancipation Proclamation, Bonekemper writes that Lincoln’s public pronouncement of that sterile statement “foreclosed European intervention” in the war.

No, no it didn’t.

The amount of European intervention in the war was substantial, though rarely reported. Perhaps just a paragraph or two from the eminent scholar Clyde Wilson will create a bit of context and demonstrate just how involved Europeans — well, a certain cadre of Europeans — were in the war…in the army of the United States:

After the failed European revolutions of 1848, many militant, aggressive Germans immigrated to the U.S., especially the Midwest. These were revolutionaries experienced in conflict, dedicated to social revolution by violence, and ignorant or contemptuous of American constitutionalism. Lincoln courted these people assiduously. It has been shown that Lincoln’s election as President was a product of the influx of Germans into the Midwest, outvoting the traditional Democratic majority there. Some of the Germans were also ignorant peasants who could be made to believe the cynical Republican lie that Southerners intended to enslave them.

These immigrant “Union” enthusiasts were proto-fascists or proto-communists. It amounts to the same thing. A number of Germans were generals in the Northern army, which also had several entire divisions composed of German immigrants. European Communists boasted that these people had played a big role in the federal government’s winning the war. This is not true—their battle record was quite poor. But it was certainly known that these German immigrants were the most brutal of Union troops in their treatment of American civilians in the South.

Remarkably, these German revolutionaries and the role they played in the leadership of the Union army merited one sentence in Bonekemper’s book and that sentence simply states that a German-American general attracted many Germans into the Union army. That’s it. No mention of socialists, communists, the record of atrocities. Nothing.

In order to provide an accurate précis of Bonekemper’s book, I’ll summarize the final chapter, a chapter called “A Comparison of Grant and Lee.”

Grant is the general that has never been treated fairly and Lee is the general who doesn’t deserve the praise heaped upon him by Northern and Southern historians alike.

Did you just roll your eyes? I understand.

Here’s a sample of the “similarities” catalogued by Bonekemper:

- Both generals were aggressive, but “Grant’s aggressiveness won the war, while Lee’s lost it.”

- Speaking of the casualties of the war, Bonekemper writes that “amazingly, almost one-fourth of Southern white males of military age died during the war.” If this were any other conflict in history, this sort of statistic would be described as “genocide,” but since the dead were Southern men during the Civil War, they are simply classified as “casualties.” As might be expected, Bonekemper lays the blame for these deaths at the feet of Robert E. Lee whose “faulty strategies and tactics” were the cause of this atrocity.

- Speaking of tactics, Bonekemper describes Lee’s tactical skills as “too complex,” “simply ineffective,” “too vague,” and “discretionary.” As for Grant, simply insert the word “not” in front of all the descriptions of Lee’s tactical deficiencies and you’d have Bonekemper’s version of Grant’s tactical genius.

- Next category is lucid and effective orders. Grant’s orders were lucid and clear, while Lee’s were not lucid and not clear. That’s about it.

- On to maneuverability. Grant was “daring and innovative.” In describing Robert E. Lee’s military maneuverability, Bonekemper uses the word “desperate” twice in one sentence. He does add the adjectives “dangerous” and “scrambling” in case doubling down on “desperate” was not enough to make the point.

- Handling their opponents. Ulysses S. Grant was a all-business and “eager to get the job done” without regard to what General Lee was doing. Lee, however, “acted on the basis of faulty assumptions” about Grant’s plans and those assumptions cost him victories in 1864 and 1865.

Finally, Bonekemper wraps up his comparison of Grant and Lee with a bizarre paragraph that at once exonerates and excuses the epithet of “butcher” that was applied to Ulysses S. Grant.

“Ulysses S. Grant has acquired the unfortunate and unfair label of ‘butcher’ because of the 1864 campaign of adhesion he conducted against Robert E. Lee to secure final victory for the Union. Grant’s dogged persistence as he moved beyond the Wilderness and Spotsylvania caused one Southerner to say, ‘We have met a man this time, who either does not know when he is whipped, or who cares not if he loses his whole army.’ During that campaign, some described him as a ‘butcher’ or ‘murderer.’ As Russell F. Weigley concluded however, ‘there is no good reason to believe that the Army of Northern Virginia could have been destroyed within an acceptable time by any other means than the hammer blows of Grant’s army.’”

So, was it unfair or was it necessary? Why explain that Lee couldn’t have been defeated without a blitzkrieg by Grant if the “butcher” label is undeserved? Shouldn’t Bonekemper have simply written that while Grant did go on an inhumane rampage it was unavoidable if the war was going to end quickly?

Moreover, wasn’t the aggressiveness described by the “one Southerner” berated by Bonekemper in his comparison of the two generals? When applied to Grant and his campaign against the Army of Northern Virginia, though, it is not only a virtue, but an excuse for excess.

Bonekemper ends his book — strangely classified by the publisher as “history” — with a sentence that is one of the few examples of economy of language in this long eulogy of Ulysses S. Grant.

“To Grant, along with Lincoln, must go the credit for Union victory, and to Lee, along with Jefferson Davis, must go the blame for Confederate defeat.”

I’ll wrap up this review by circling back to the beginning. Were one tasked with editing Bonekemper’s book, he could rework the final sentence thus, in order to make it more historically accurate:

“To Lincoln must go the blame for the Southern genocide of 1861-1865, and to Lee goes the credit for defending his life, liberty, and property against an unconstitutional invasion of all three by a president bent on breaking his oath of office.”

Bonekemper was an extremely dishonest and biased historian, and trusting any of his garbage (emphasis, garbage) is a recipe for misunderstanding.