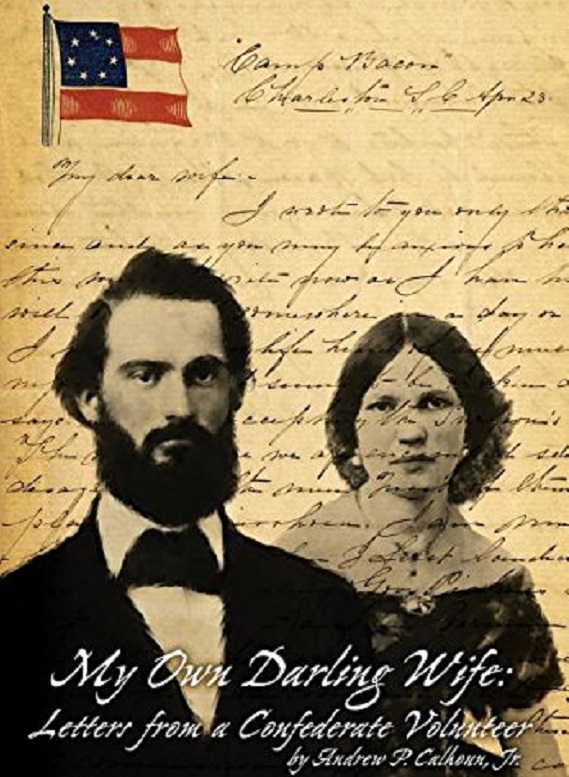

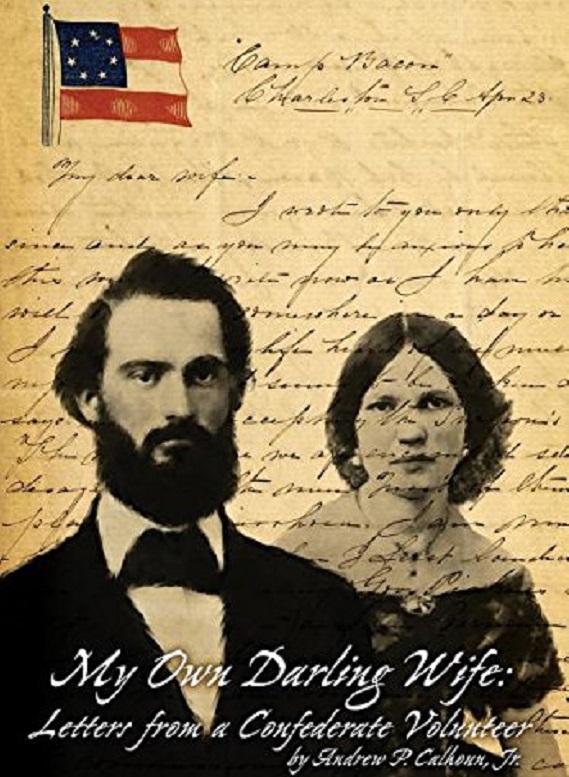

A review of My Own Darling Wife: Letters from a Confederate Volunteer by Andrew P. Calhoun (Shotwell Publishing, 2018).

This is not just a book of family letters from the War Between the States. You will learn more about the typical Confederate soldier in these 208 pages than in most books.

The author of these letters is John Francis Calhoun, a lieutenant in Company C, 7th Regiment, South Carolina Volunteers, and they were sent home to his wife Rebecca, who he requested keep them for him. John Francis was grand-nephew of the Hon. John C. Calhoun; Rebecca was great-granddaughter of Gen. Andrew Pickens, so the family was steeped in South Carolina history.

These letters cover Calhoun’s experiences in the Confederate Army for 12 months, from April 1861 to March 1862. He called her letters to him “jewels”. Being an officer gave him an overview between the commissioned officers in command and the enlisted troops he commanded.

Pay: “Yesterday was pay day and we were all paid of [sic] and in turn ‘paid off ourselves.’ It is expensive living now that is for the officers, as we furnish everything in proportion.” He told her of the prices of commodities, and how expensive they were from when he left for The War, and how coffee disappeared from the menu and was too expensive to purchase on the local economy.

Sickness: In April 1861 he wrote, “I never in my life heard of as much sickness. Dr. [John Wardlaw] Hearst seems to be broken down and says he regrets accepting the surgeon’s post.” By August he wrote, “We have a great deal of sickness in our Regt and the entire Brigade. There are between 3 and 400 reported unfit for duty in our Regt alone.”

Sickness he told her was brought about by lack of tents and blankets. “I sleep under two and three blankets and my feet are cool all night at that.” At the end of November he wrote, “I got up two hours before day this morning. I was so cold. The ice was more than an inch thick. The ground was frozen all day and tonight will be very cold again.” By February 1862 he could say, “We have awful weather and if we could get wood enough and had no picketing to do we could make out very well.”

Tents. In March 1862 he wrote, “[Wade Elephare] Cothran and I made us a tent by ripping mattress tick, and by using blankets and we are fixed up tolerably comfortable, we can’t stand up but it keeps the rain off which is all we want, having blankets enough.”

Clothing. In addition to blankets and tents, he wrote home about clothing he needed. “Make up those grey pants and two pair of stout drawers and two or three shirts as I will need them if I have to stay here even until Oct.”

Envelopes were difficult to come by, so in August of 1861 he asked her to send him a “bunch of thick white envelopes” and he reminded her that postage to his unit was only five cents, which was stamped on the envelopes from her. He asked for pictures of his wife and his child.

Since he was nearby to Manassas, he wrote her several letters about the battle and what was left by the enemy, the “spoils” of war. They had left 20,000 stand of weapons, artillery, and food. The Confederates had to bury the enemy, and he told of how little they were buried. This was not only new for soldiers but for those back home too.

He also wrote her of what the troops were doing. “Whilst I am writing some of the boys are cooking biscuit, making coffee, frying meat &c and it would surprise you to see how well they cook. Some of hem [sic] killed a large fat unmarked hog and I will enjoy a breakfast of ribs. The yankee residents who fled from this country left cattle, hogs &c. and the soldiers kill them whenever they can get a chance.”

Other letters tell her what needed to be done at their farm, showing how people lived during The War in an agricultural area. Calhoun also owned and ran a tannery, producing leather for the Confederacy.

Calhoun survived The War and later joined Clemson College as dining hall bursar and his wife as dormitory matron. His other duty was curator of the relic room at Clemson.

This is not just a book of letters, but a history of a family in The War, and a history of soldiers in The War. Except for the cover, there are no illustrations, but a good introduction and epilogue. People named in the letters are explained in footnotes.

This book is a welcome addition to the information about The War.