A Review of The Election of 1860: “A Campaign Fraught with Consequences” by Michael F. Holt (University Press of Kansas, 2017).

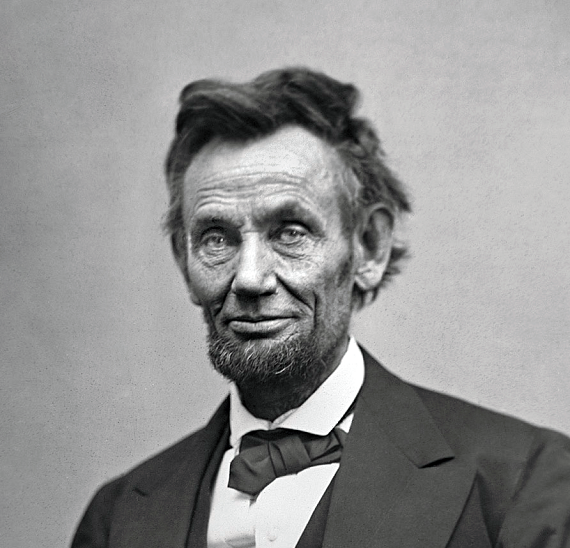

Chapter One of Michael F. Holt’s contribution to the corpulent body of work covering the election of 1860 is called “Republican Storm Rising” and it was political perfect storm that blew Abraham Lincoln into the White House.

One of, if not the most valuable contribution Holt makes to this burnt over district of scholarship is his insistence, from the very beginning, that the historical result of the 1860 election was not the apotheosis of a “man for all seasons,” in the form of Abraham Lincoln. No, Lincoln’s victory was propelled by the fire of party strife and the splintering of support of Lincoln’s otherwise worthy candidates.

Holt demonstrates his appreciation of the hyper-partisanship of the time by provided ample biographies of the four presidential candidates: Republican Abraham Lincoln; Northern Democrat Stephen A. Douglas; Southern Democrat John C. Breckinridge; and John Bell of the Constitutional Union Party.

This compact chronicle of the presidential campaign leading to Lincoln’s administration focuses much less on the drama of the day — election day — and more on the interpretation of the results of the election as seen through the lens of party platform, sectionalism, and social unrest spreading out from several population centers from across the increasingly internecine union of states.

As is the case in so many election years that come after one party has occupied the Oval Office for two terms, in 1860 the Republicans got an boost from a bloc of voters who were not so much committed to the cause of the GOP, but were tired of the Democrats and the widely perceived power-abuse committed by that party’s leadership for the past eight years. Holt makes this point very clearly and convincingly in his book.

Perhaps the only short-coming in Holt’s coverage of the key issues in the election of 1860 is the brevity of his description of the devastating effect the controversy over the constitution (pro-slavery) being proposed by those pushing for Kansas statehood. While Holt does mention this electoral grenade, his coverage of just how far the shrapnel flew and just how much damage to the Democrats it inflicted is shorter than it should be.

Holt’s account of the events shines again, though, when it comes to completely cutting the legs out from under the popularly promoted fallacy that Lincoln was the less radical of the non-Democratic options.

This is so demonstrably untrue and so easily debunked, it is a wonder so many people have for decades perpetuated this myth.

For Holt, Lincoln’s acceptability was due in large measure to the desire of Republicans to sink deep roots into the quickly expanding West, a region from which Lincoln hailed and was believed to understand.

Apart from his perceived sectional superlative, Holt points to the bloodthirsty infighting among the other candidates as the most salient reason for his rise to the White House.

Slavery was, in Holt’s view, an important issue, but not for the reasons typically assigned in the academic treatment of the election of 1860. In Holt’s estimation, the Republican Party’s seemingly successful management of the slavery question in Kansas convinced the party’s leadership that slavery would not be an issue the pro-slavery parties or candidates would be keen on pushing. They were wrong.

Southern Democrats reckoned they could make slavery into an issue that motivate voters to the polls, using ballots to avenge what they saw as the bribes that put Kansas in the pocket of the Republicans.

This turned out to be a misjudgment that made Lincoln’s election all but a sure thing. The Southerners couldn’t agree which candidate would be the most reliably pro-slavery and John Bell and Stephen A. Douglas found themselves allies in the effort to marginalize as extremists both the Southern Democrats and Republicans.

An interesting and timely take on the events comes from Holt’s report that Bell and the Constitutional Union Party were ridiculed by many partisans for that party’s insistence on the rigid hewing to plain principles of the U.S. Constitution, many of them mocking “the party’s say-nothing platform.”

Of course, the fact that Bell, a Tennessean, was not pro-slavery did not sit well with many of his fellow southerners, particularly the politicians and more particularly the Southern Democrats.

The Constitutional Union Party’s promise to enforce anti-slavery laws passed by Republicans prompted the Southern Democrats to say that it was “preposterous in the extreme for any party to attempt to ignore the slavery issue, when no less than six important territorial bills are pending in Congress, and all are aimed at the vital interests of the South, and supported by the Republican party.”

As for the Republicans, Holt points out that despite the hue and cry from Democrats, slavery was not the reason their party’s platform was controversial. In a move reminiscent of John Adams and the Federalists’ enactment of the Alien Laws, the Republican Party in Massachusetts supported an amendment to the Massachusetts State Constitution that required naturalized citizens to wait two years before they could vote. The idea was to create an unbeatable coalition with the Know Nothing party who pushed for passage of the amendment.

The Republican Party nationally benefitted from the membership and support of many influential Germans. These Germans threatened to abandon the national GOP should they not come out in opposition to the anti-immigrant amendment in Massachusetts.

As a result, the Republican Party’s national platform included what became known as the “German plank.” The statement opposed “any change in our Naturalization Laws or any State legislation by which the rights of citizenship hitherto accorded to immigrants from foreign lands shall be abridged or impaired.”

The Republicans knew on which side their brot was buttered!

As for Abraham Lincoln, he understood that palms had to be greased and promised had to be made. Accordingly, Indiana’s vote at the convention was secured by a promise to put a Hoosier on Lincoln’s cabinet.

Lincoln reportedly wanted to avoid the appearance of favoring his friends, but his campaign soldiers in the political trenches chose to ignore these orders, according to Holt.

“Lincoln ain’t here and don’t know what we have to meet, so we will go ahead as if we hadn’t heard from him, and he must ratify it,” said David Davis, Lincoln’s friend and the leader of the bloc working to keep Seward from getting the nomination.

Next, Holt describes in detail the political winds that blew Lincoln into power. He attributes Lincoln’s election not to any ardent support of the candidate, rather it was the Republican Party bosses’ ability to make Abe look more honest than the corrupt and crooked “Goths and Vandals” that had occupied the palaces of power on the Potomac. Given the putrid gas coming off that swamp, Lincoln was easily portrayed as, if not pure, than purer than the alternative.

Finally, while his narrative is readable and his chronicle of the historical and in many ways unique events that were part of the election of 1860, the most valuable contribution made by Holt’s The Election of 1860: A “Campaign Fraught with Consequences” comes from his appendices.

The appendices include the 1860 election returns, the parties’ platforms, and Lincoln’s inaugural address from 1861.

If one read nothing but the last of these documents, he would go a long way toward gaining greater insight — more accurate insight — into the election of 1860 than he could get from any more popular account of the era or from the tales told in textbooks