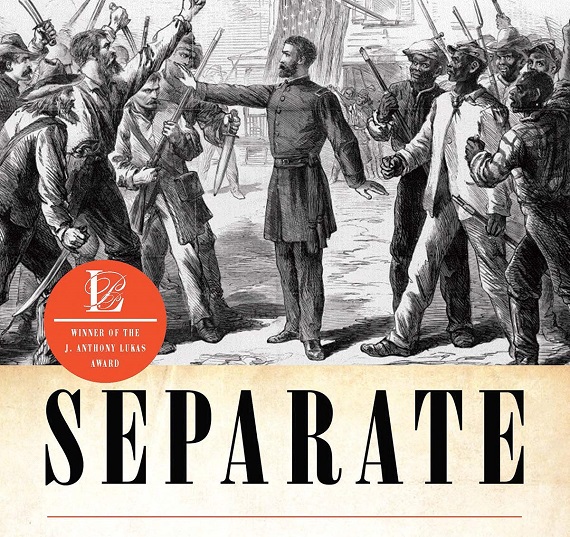

A Review of Separate: The Story of Plessy v. Ferguson, and America’s Journey from Slavery to Segregation (W.W. Norton, 2019) by Steve Luxenberg

In 21st-Century America, there are precious few mediums through which the issue of race can be addressed with even a modicum of rationality. One of the few means still available is the thorough, well-researched work produced by historians. Perhaps the only reason this avenue is still available to us at all is because those whom you would expect to participate in protests over its content do not usually spend the required time for reading books or truly studying history.

Steve Luxenberg, associate editor of The Washington Post, is on the left end of the political spectrum, but his treatment of the indelible Supreme Court case Plessy v. Ferguson deserves credit for valuing the truth in a time when doing so concerning race can initiate such remonstrance from the usual suspects.

After twelve years of Reconstruction and the Compromise of 1877, which maintained the Republican hold on the White House by placing Rutherford B. Hayes in the chief executive chair, federal troops were finally withdrawn from the South and Southerners began taking back control of their State legislatures. If we are to believe the elementary-school version of the period, this is when those evil, white Southerners began reasserting themselves by putting the black race back in its place, thereby rejecting all the enlightened policies produced by the righteous Yankee, who had emancipated the black man, granted him equal rights, and embraced him as a fellow citizen. That is not the truth and Luxenberg, again, to his credit, does not shy away from it.

Comically, however, before diving in Luxenberg felt it necessary to include an “Author’s Note” before the Prologue. This obligatory disclaimer forms a politically-correct conjunction with an MLK quote preceding the first chapter (MLK is found nowhere else in the book) that serves as somewhat of an apology from the author to any reader whose tender sensibilities might be aggrieved by monstrosities like “labels such as ‘colored’ and ‘mulatto.’” Mind you, these “labels” were used indiscriminately for centuries by advocates and blacks themselves through at least the 1960s. Alas, when a white male (even a writer from The Washington Post) actually puts such dastardly things in print today in a book that has a chapter entitled “’The Negro Question’” (smelling salts please!), he probably thinks it best to cover all the (white) bases.

Plessy dealt with a law passed by the State of Louisiana in 1890 called the Separate Car Act, which enforced separation of races on different railroad cars. Opponents of the law orchestrated a prearranged arrest where Homer Plessy (who could pass for white and was only 1/8 black) was taken into custody for refusing to move from the white car to the “Jim Crow” car.

Ah, Jim Crow. Wikipedia informs us these were laws that “mandated racial segregation in all public facilities in the states of the former Confederate States of America…” Britannica.com says they were laws that “enforced racial segregation in the American South between the end of Reconstruction in 1877 and the beginning of the civil rights movement in the 1950s.”

The problem with these definitions is that they are utterly false. Jim Crow laws predated the Confederacy and have their origins in…the North. Luxenberg relates this in the first pages of the first chapter, where he writes “[s]eparation had no role in the South before the Civil War… It was the free and conflicted North that gave birth to separation… One of those birthplaces was the Massachusetts town of Salem.” He goes on to recount in detail how, even though blacks comprised but one percent of Massachusetts’s population, “Jim Crow” became a “commonly understood phrase in New England’s lexicon” by the late 1830s. On September 8, 1841, Frederick Douglass himself experienced a healthy dose of Yankee tolerance when he was forcibly ejected off a white car on the way from Salem to Portsmouth, New Hampshire.

Luxenberg devotes a large portion of his book (perhaps too large) to detailing the lives of three of the central players in this story, as well as the mixed-race history of New Orleans that made it such a unique setting for the testing of racial separation laws. Of the three men, we see long sketches of two justices who were born into privileged, well-connected worlds where advantage was bestowed at birth. The third man would argue the Plessy case in front of the other two and their colleagues in 1896. He was not so advantaged, and he was not so successful. He made a name for himself by exploiting the South and championing social equality.

Albion Tourgee was born in Ohio and served in the Union army during the War Between the States. After being ignobly wounded during a full-scale retreat from Manassas he was captured, imprisoned, and ultimately released. He then became a 19th-century social justice warrior. He “carpetbagged” to North Carolina immediately after the war and lived there for fifteen years. One local newspaper referred to him as the most hated man in that State. Intensely ambitious, he once wrote to his bride-to-be while courting, “My success – if I am successful – will then be attributable only to myself.”

One episode from his Carolina days demonstrates Tourgee’s propensity for fantastical embellishments and self-flattery. In 1868, he gave a speech in front of the North Carolina State Constitutional Convention in which he marked his social justice awakening with what he witnessed at the scene of the Fort Pillow massacre during the war, “a picture photographed forever on my mind.” It was a moving and dramatic performance by Tourgee. But when the incident he referred to took place in Tennessee in April 1864, he had already resigned from the army and moved back to Ohio, his military career over.

Incredulous to his immense unpopularity in North Carolina, Tourgee decided to run for Congress there in 1878. The Raleigh Observer wrote that Tourgee had “rode roughshod over us” and “now the wretch is down on his all-fours begging us humbly for office as a mangy cur would for a bone.” Tourgee, already abandoned by his wife and child, lost badly and sunk into one of his recurring bouts of despair. He wrote home, “I just wish to die.” Instead, he limped back to his family and experienced years of debts, lawsuits, and failed business deals. He would have success writing novels about the South and making friends with black leaders, who recruited him to argue their case in Plessy.

John Marshall Harlan was born in Kentucky and would be the only Plessy justice on the Supreme Court from the South. Ironically, he would also be the only dissenter.

Harlan had a pro-slavery upbringing. Like fellow Kentuckians Henry Clay and Abraham Lincoln, his father favored colonization of the black race by removing them from the country and settling them somewhere else. Harlan married a girl from Indiana, just across the 1000-mile-long Ohio River that served as a liquid Mason-Dixon Line. Again, showing a regard for the truth over South-bashing, the author notes that the “free” State of Indiana had a brand new constitution in 1851 that included a clause prohibiting any blacks from settling in their State. This should remind students of history that a significant reason the North was better at avoiding racial issues than the South was that Northerners made every effort to avoid blacks altogether.

Harlan spent his young adulthood drifting from political party to political party, finally throwing in with Lincoln and the Republicans at the outbreak of hostilities. His father became U.S. district attorney for Kentucky in Lincoln’s administration and John fought for the Union, all the while emphasizing while recruiting that he was fighting to preserve the Union and not against slavery.

In 1864, Harlan supported George McClellan for president over Lincoln, whom Harlan blamed for “usurping powers that rightly belonged to the States.” This would haunt him in future Republican politics. He spent two subsequent campaigns for Kentucky governor trying to explain himself. He lost both, “tweaked” his political views, and shifted the focus of his desire for office and prestige to the national capital, instead. He gained favor with President Grant and in 1877 was nominated for the Supreme Court by Hayes. In his confirmation hearing, Harlan again had to answer for his lifelong anti-Republican views. It is not unfair to conclude that Harlan succumbed to that great killer of convictions – ambition.

Henry Billings Brown was born in Massachusetts and lived in Michigan before becoming a Supreme Court justice. He would author the majority decision in Plessy. Brown grew up uncertain of himself and hesitant about his future. He graduated from Yale yet lamented his own “incorrigible laziness.” In adulthood he rejected abolitionism and all extremism and was drawn to the more temperate and moderate voices within the Republican Party. He spent considerable time and effort cultivating and amassing contacts for future gain. His connections led to his first federal job at the outset of the war – a war he avoided fighting in by paying $850 for a “substitute” to legally avoid the draft. Pampered and out of touch with the common man, Brown once paid two thousand dollars in one afternoon for art in Brussels in 1875. He was a perennial office-seeker and evolved into a consummate politician.

The setting for the arrest was the city of New Orleans, a three-tiered society inhabited by whites, former slaves, and free blacks of mixed descent (mainly French or European, “Creole”) who had never been slaves (les gens de couleur libres). The latter was a mixed variety of complexions and ethnicities and included free black slaveowners and former slaves turned slaveowners (those pushing slave reparations today should try crunching the numbers for that). The color line in the Crescent City blurred like nowhere else in the United States.

Like John Harlan’s Kentucky, Northern States, and all Union-occupied territory in the South, the text of the Emancipation Proclamation explicitly excluded New Orleans slaves from liberation. In the chaotic atmosphere that ensued, military authorities there elected to control the swelling tide of runaway slaves by making mass arrests. Free people of color, born free and having never been slaves, were caught up in the wholesale strategy carried out by Northern soldiers, most of whom had so little experience with blacks in their lives that they reckoned that anyone with a dark complexion must be a slave.

Luxenberg writes, “For free people of color, the irony was inescapable. The Emancipation Proclamation, a document of freedom and joy for so many, was now resulting in harassment and humiliation for them.” These same free blacks were shoved to the sidelines after the war by Reconstruction authorities, denied the right to vote or be involved in the new “free” government of Louisiana.

Indeed, if the free or recently freed black person thought the victorious Union was going to grant them the equality envisioned by many, they would see in the decades after the war that they were sorely mistaken. Luxenberg lays out several examples, including citizens of the State of Michigan voting down black suffrage in 1868. In 1867 the Pennsylvania Supreme Court, comprised entirely of white Republicans, blessed racial separation on their railroad cars.

The Radical Republicans in Congress pushed through the Civil Rights Act of 1875, which immediately met stiff resistance and questions of constitutionality North and South. In 1883, the U.S. Supreme Court itself declared the act unconstitutional, the lone dissenter being John Harlan.

Unlike the lily white cities and States of the North, the confusing complexion of New Orleans was considered to be fertile ground for planting the seeds of a federal lawsuit that proponents hoped would land back in the lap of “that eminent tribunal.”

The Plessy team found accomplices in the railroad directors of Louisiana, who agreed to be “silent partners” to the staged arrest. Why? They were businessmen, after all, and the bottom line was what mattered most. Having to maintain extra cars to handle what amounted to a relatively few amount of black customers did not make economic sense to them.

Plessy was almost known to history as Desdunes. On February 24, 1892, Daniel Desdunes was arrested for refusing to leave the white car after boarding a railroad car in New Orleans, bound for Mobile, Alabama. But that May the Louisiana Supreme Court ruled that the Separate Car Act could not be enforced on interstate travelers. Undeterred, the challengers began seeking a new defendant.

Enter Homer Plessy. On June 7, 1892, he boarded a white car in New Orleans with a ticket for Covington, sixty miles north on the shore of Lake Pontchartrain. He was arrested when he refused to change cars. His case was appealed to Louisiana’s highest court, where Judge John H. Ferguson ruled in favor of the fairness of “separate but equal” facilities. Plessy appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court, whereby he became a plaintiff and the ruling judge became the defendant – Plessy v. Ferguson.

Throughout the episode, Tourgee seemed overly optimistic given his assessment of the justices. He wrote his co-counsel that their only hope was a 5-4 decision, since he presumed that four of them “will probably stay where they are until Gabriel blows his horn… It’s hardly doubtful we have a Court somewhat adverse to our views.”

It turned out only eight justices would decide the case, one being with his family as they grieved the death of his daughter. Of the seven Northerners, all had corporate and privileged backgrounds.

In light of the decision thirteen years prior where the Court struck down the Civil Rights Act of 1875 as unconstitutional, what followed seemed to surprise no one but the Plessy legal team. Justice Brown of Michigan wrote for the 7-1 majority, endorsing custom, preference, precedent, the “inherent” reserved police powers of a State, and the “separate but equal” doctrine. Brown wrote that social prejudices cannot be overcome by legislation. “Legislation is powerless to eradicate racial instincts…” The lone dissenter, again, was Kentuckian John Harlan.

For the most part, newspapers paid little attention to the decision. The matter was considered settled.

By 1912, Brown had not changed his mind. In an article published that year, he wrote that the Constitution could ensure political rights, but not “social rights.”

In just 58 years the same court that handed down a 7-1 decision approving the “separate but equal” doctrine would unanimously overturn that in Brown v. Board of Education.

Plessy v. Ferguson is considered a landmark case in U.S. history. But the intricate details involving the cast of characters, the history of race relations in the North and in New Orleans, and the strategy employed by the Plessy legal team are largely unknown. Separate does a very good job of laying them out for us.

Originally published at the Fleming Foundation.