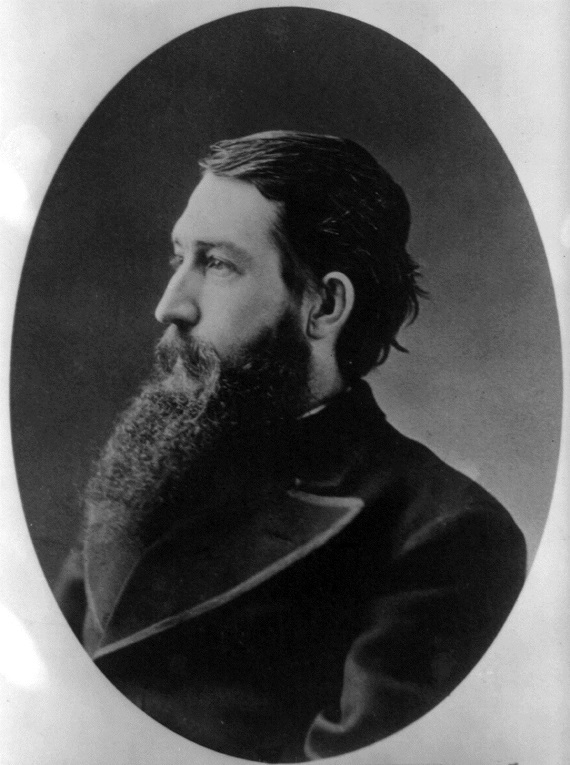

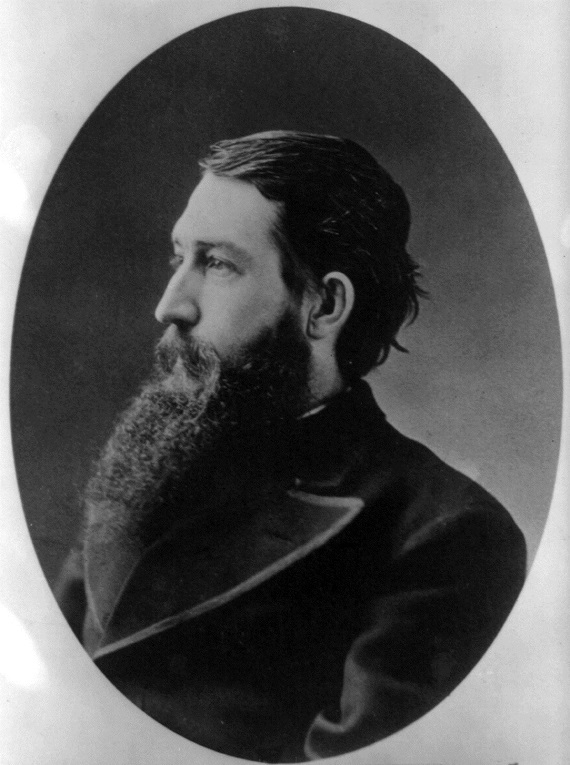

BECAUSE I believe that Sidney Lanier was much more than a clever artisan in rhyme and metre; because he will, I think, take his final rank with the first princes of American song, I am glad to provide this slight memorial. There is sufficient material in his letters for an extremely interesting biography, which could be properly prepared only by his wife. These pages can give but a sketch of his life and work.

Sidney Lanier was born at Macon, Ga., on the third of February, 1842. His earliest known ancestor of the name was Jerome Lanier, a Huguenot refugee, who was attached to the court of Queen Elizabeth, very likely as a musical composer; and whose son, Nicholas, was in high favor with James I. and Charles I., as director of music, painter, and political envoy; and whose grandson, Nicholas, held a similar position in the court of Charles II. A portrait of the elder Nicholas Lanier, by his friend Van Dyck, was sold, with other pictures belonging to Charles I., after his execution. The younger Nicholas was the first Marshal, or presiding officer, of the Society of Musicians, incorporated at the Restoration, “for the improvement of the science and the interest of its professors;” and it is remarkable that four others of the name of Lanier were among the few incorporators, one of them, John Lanier, very likely father of the Sir John Lanier who fought as Major-General at the Battle of the Boyne, and fell gloriously at Steinkirk along with the brave Douglas.

The American branch of the family originated as early as 1716 with the immigration of Thomas Lanier, who settled with other colonists on a grant of land ten miles square, which includes the present city of Richmond, Va. One of the family, a Thomas Lanier, married an aunt of George Washington. The family is somewhat widely scattered, chiefly in the Southern States.

The father of our poet was Robert S. Lanier, a lawyer still living in Macon, Ga. His mother was Mary Anderson, a Virginian of Scotch descent, from a family that supplied members of the House of Burgesses of Virginia for many years and in more than one generation, and was gifted in poetry, music, and oratory.

His earliest passion was for music. As a child he learned to play, almost without instruction, on every kind of instrument he could find; and while yet a boy he played the flute, organ, piano, violin, guitar, and banjo, especially devoting himself to the flute in deference to his father, who feared for him the powerful fascination of the violin. For it was the violin-voice that, above all others, commanded his soul. He has related that during his college days it would sometimes so exalt him in rapture, that presently he would sink from his solitary music-worship into a deep trance, thence to awake, alone, on the floor of his room, sorely shaken in nerve.

In after years more than one listener remarked the strange violin effects which he conquered from the flute. His devotion to music rather alarmed than pleased his friends, and while it was here that he first discovered that he possessed decided genius, he for some time shared the early notion of his parents, that it was an unworthy pursuit, and he rather repressed his taste. He did not then know by what inheritance it had come to him, nor how worthy is the art.

At the age of fourteen he entered the sophomore class of Oglethorpe College, an institution under Presbyterian control near Midway, Ga., which had not vitality enough to survive the war. He graduated in 1860, at the age of eighteen, with the first honors of his class, having lost a year during which he took a clerkship in the Macon post-office. At least one genuine impulse was received in this college life, and that proceeded from Professor James Woodrow, who was then one of Sidney’s teachers, and who has since been connected with the University and Theological Seminary in Columbia, S. C. During the last weeks of his life Mr. Lanier stated that he owed to Professor Woodrow the strongest and most valuable stimulus of his youth. Immediately on his graduation he was called to a tutorship in the college, which position he held until the outbreak of the war.

And here, with some hesitation, I record, as a true biography requires, the development of his consciousness of possessing real genius. One with this gift has a right to know it, just as others know if they possess talent or shiftiness of resource. While we do not talk so much of genius now as we did a generation ago, we can yet recognize the difference between the fervor of that divine birth and the cantering of the livery Pegasus forth and back, along the vulgar boulevards over which facile talent rides his daily hack. Only once or twice, in his own private note-book, or in a letter to his wife when it was needful, in sickness and loneliness, to strengthen her will and his by testifying his own deepest consciousness of power, did he whisper the assurance of his strength. But he knew it, and she knew it, and it gave his will a peace in toil, a sun-lit peace, notwithstanding sickness, or want, or misapprehension, calm above the zone of clouds.

As I have said, his genius he first fully discovered in music. I copy from his pencilled college note-book what cannot have been written after he was eighteen years old. The boy had been discussing the question with himself how far his inclinations were to be regarded as indicating his best capacities and his duties. He says:

“The point which I wish to settle is merely, by what method shall I ascertain what I am fit for, as preliminary to ascertaining God’s will with reference to me; or what my inclinations are, as preliminary to ascertaining what my capacities are, that is, what I am fit for. I am more than all perplexed by this fact, that the prime inclination, that is, natural bent (which I have checked, though) of my nature is to music; and for that I have the greatest talent; indeed, not boasting, for God gave it me, I have an extraordinary musical talent, and feel it within me plainly that I could rise as high as any composer. But I cannot bring myself to believe that I was intended for a musician, because it seems so small a business in comparison with other things which, it seems to me, I might do. Question here, What is the province of music in the economy of the world?”

Similar aspirations he felt at this early age, probably eighteen, for grand literary labor, as the same note-book would bear witness. We see here the boy talking to himself, a boy who had found in himself a standard above anything in his fellows.

The breaking out of the war summoned Sidney Lanier from books to arms. In April, 1861, he enlisted in the Confederate Army, with the Macon Volunteers of the Second Georgia Battalion, the first military organization which left Georgia for Virginia. From his childhood he had had a military taste. Even as a small boy he had raised a company of boys armed with bows and arrows, and so well did he drill them that an honored place was granted them in the military parades of their elders. Having volunteered as a private at the age of nineteen, he remained a private till the last year of the war. Three times he was offered promotion and refused it because it would separate him from his younger brother, who was his companion in arms, as their singularly tender devotion would not allow them to be parted. The first year of service in Virginia was easy and pleasant, and he spent his abundant leisure in music and the study of German, French, and Spanish. He was in the battles of Seven Pines, Drewry’s Bluffs, and the seven days’ fighting about Richmond, culminating in the terrible struggle of Malvern Hill. After this campaign he was transferred, with his brother, to the signal service, the joke among his less fortunate companions being that he was selected because he could play the flute. His headquarters were now for a short period at Petersburg, where he had the advantage of a small local library, but where he began to feel the premonitions of that fatal disease, consumption, against which he battled for fifteen years. The regular full inspirations required by the flute probably prolonged his life. In 1863 his detachment was mounted and did service in Virginia and North Carolina. At last the two brothers were separated, it coming in the duty of each to take charge of a vessel which was to run the blockade. Sidney’s vessel was captured, and he was for five months in Point Lookout prison, until he was exchanged (with his flute, for he never lost it), near the close of the war. Those were very hard days for him, and a picture of them is given in his “Tiger Lilies,” the novel which he wrote two years afterward. It is a luxuriant, unpruned work, written in haste for the press within the space of three weeks, but one which gave rich promise of the poet. A chapter in the middle of the book, introducing the scenes of those four years of struggle, is wholly devoted to a remarkable metaphor, which becomes an allegory and a sermon, in which war is pictured as “a strange, enormous, terrible flower,” which “the early spring of 1861 brought to bloom besides innumerable violets and jessamines.” He tells how the plant is grown; what arguments the horticulturists give for cultivating it; how Christ inveighed against it, and how its shades are damp and its odors unhealthy; and what a fine specimen was grown the other day in North America by “two wealthy landed proprietors, who combined all their resources of money, of blood, of bones, of tears, of sulphur, and what not, to make this the grandest specimen of modern horticulture.” “It is supposed by some,” says he, “that seed of this American specimen (now dead) yet remains in the land; but as for this author (who, with many friends, suffered from the unhealthy odors of the plant), he could find it in his heart to wish fervently that this seed, if there be verily any, might perish in the germ, utterly out of sight and life and memory, and out of the remote hope of resurrection, forever and ever, no matter in whose granary they are cherished!” Through those four years, though earnestly devoted to the cause, and fulfilling his duties with zeal, his horror of war grew to the end. He had entered it in a “crack” regiment, with a dandy uniform, and was first encamped near Norfolk, where the gardens, with the Northern market hopelessly cut off, were given freely to the soldiers, who lived in every luxury; and every man had his sweetheart in Norfolk. But the tyranny and Christlessness of war oppressed him, though he loved the free life in the saddle and under the stars.

In February, 1865, he was released from Point Lookout and undertook the weary return on foot to his home in Georgia, with the twenty-dollar gold piece which he had in his pocket when captured, and which was returned to him, with his other little effects, when he was released. Of course he had the flute, which he had hidden in his sleeve when he entered the prison, and which had earned him some comforts. He reached home March 15th, with his strength utterly exhausted. There followed six weeks of desperate illness, and just as he began to recover from it his beloved mother died of consumption. He himself arose from his sick-bed with pronounced congestion of one lung, but found relief in two months of out-of-door life with an uncle at Point Clear, Mobile Bay. From December, 1865, to April, 1867, he filled a clerkship in Montgomery, Ala., and in the next month, made his first visit to New York on the business of publishing his “Tiger Lilies,” written in April. In September, 1867, he took charge of a country academy of nearly a hundred pupils in Prattville, Ala., and was married in December of the same year to Miss Mary Day, daughter of Charles Day, of Macon.

To the years before Mr. Lanier’s marriage belong a dozen poems included in this volume. Two of them are translations from the German made during the war; the others are songs and miscellaneous poems, full of flush and force, but not yet moulded by those laws of art of whose authority he had hardly become conscious. His access to books was limited, and he expressed himself more with music than with literature, taking down the notes of birds, and writing music to his own songs or those of Tennyson.

In January, 1868, the next month after his marriage, he suffered his first hemorrhage from the lungs, and returned in May to Macon, in very low health. Here he remained, studying and afterward practising law with his father, until December, 1872. During this period there came, in the spring and summer of 1870, a more alarming decline with settled cough. He went for treatment to New York, where he remained two months, returning in October greatly improved and strong in hope; but again at home he lost ground steadily. He was now fairly engaged in the brave struggle against consumption, which could have but one end. So precarious already was his health that a change of residence was determined on, and in December, 1872, he went to San Antonio, Texas, in search of a permanent home there, leaving his wife and children meanwhile at Macon. But the climate did not prove favorable and he returned in April, 1873.

During these five years a sense of holy obligation, based on the conviction that special talents had been given him, and that the time might be short, rested upon Lanier, until it was impossible to resist it longer. He felt himself called to something other than a country attorney’s practice. It was the compulsion of waiting utterance, not yet enfranchised. From Texas he wrote to his wife:

“Were it not for some circumstances which make such a proposition seem absurd in the highest degree, I would think that I am shortly to die, and that my spirit hath been singing its swan-song before dissolution. All day my soul hath been cutting swiftly into the great space of the subtle, unspeakable deep, driven by wind after wind of heavenly melody. The very inner spirit and essence of all wind-songs, bird-songs, passion-songs, folk-songs, country-songs, sex-songs, soul-songs and body-songs hath blown upon me in quick gusts like the breath of passion, and sailed me into a sea of vast dreams, whereof each wave is at once a vision and a melody.”

Now fully determined to give himself to music and literature so long as he could keep death at bay, he sought a land of books. Taking his flute and his pen for sword and staff, he turned his face northward. After visiting New York he made his home in Baltimore, December, 1873, under engagement as first flute for the Peabody Symphony Concerts.

With his settlement in Baltimore begins a story of as brave and sad a struggle as the history of genius records. On the one hand was the opportunity for study, and the full consciousness of power, and a will never subdued; and on the other a body wasting with consumption, that must be forced to task beyond its strength not merely to express the thoughts of beauty which strove for utterance, but from the necessity of providing bread for his babes. His father would have had him return to Macon, and settle down with him in business and share his income, but that would have been the suicide of every duty and ambition. So he wrote from Baltimore to his father. November 29, 1873:

“I have given your last letter the fullest and most careful consideration. After doing so I feel sure that Macon is not the place for me. If you could taste the delicious crystalline air, and the champagne breeze that I’ve just been rushing about in, I am equally sure that in point of climate you would agree with me that my chance for life is ten times as great here as in Macon. Then, as to business, why should I, nay, how can I, settle myself down to be a third-rate struggling lawyer for the balance of my little life, as long as there is a certainty almost absolute that I can do some other thing so much better? Several persons, from whose judgment in such matters there can be no appeal, have told me, for instance, that I am the greatest flute-player in the world; and several others, of equally authoritative judgment, have given me an almost equal encouragement to work with my pen. (Of course I protest against the necessity which makes me write such things about myself. I only do so because I so appreciate the love and tenderness which prompt you to desire me with you that I will make the fullest explanation possible of my course, out of reciprocal honor and respect for the motives which lead you to think differently from me.) My dear father, think how, for twenty years, through poverty, through pain, through weariness, through sickness, through the uncongenial atmosphere of a farcical college and of a bare army and then of an exacting business life, through all the discouragement of being wholly unacquainted with literary people and literary ways – I say, think how, in spite of all these depressing circumstances, and of a thousand more which I could enumerate, these two figures of music and of poetry have steadily kept in my heart so that I could not banish them. Does it not seem to you as to me, that I begin to have the right to enroll myself among the devotees of these two sublime arts, after having followed them so long and so humbly, and through so much bitterness?”

What could his father do but yield? And what could he do during the following years of his son’s fight for standing-room on the planet but help? But for that help, generously given by his father and brother, as their ability allowed, at the critical times of utter prostration, the end would not have been long delayed. For the little that was necessary to give his household a humble support it was not easy for the most strenuous young author to win by his pen in the intervals between his hemorrhages. He asked for very little, only the supply of absolute necessities, what it would be easy for a well man to earn, but what it was very hard for a man to earn scarce able to leave his bed, dependent on the chance income had from poems and articles in magazines that would take them, or from courses of lectures in schools. Often for months together he could do no work. He was driven to Texas, to Florida, to Pennsylvania, to North Carolina, to try to recover health from pine breaths and clover blossoms. Supported by the implicit faith of one heart, which fully believed in his genius, and was willing to wait if he could only find his opportunity, his courage never failed. He still kept before himself first his ideal and his mission, and he longed to live that he might accomplish them. It must have been in such a mood that, soon after coming to Baltimore, he wrote to his wife, who was detained in the South:

“So many great ideas for Art are born to me each day, I am swept away into the land of All-Delight by their strenuous sweet whirlwind; and I find within myself such entire, yet humble, confidence of possessing every single element of power to carry them all out, save the little paltry sum of money that would suffice to keep us clothed and fed in the meantime.

“I do not understand this.”

Lanier’s was an unknown name, and he would write only in obedience to his own sense of art, and he did not fit his wares to the taste of those who buy verse. It was to comfort his wife, in this period of greatest uncertainty whether he had not erred in launching in the sea of literature, that he wrote again a letter of frankest confession:

“I will make to thee a little confession of faith, telling thee, my dearer self, in words, what I do not say to my not-so-dear-self except in more modest feeling.

“Know, then, that disappointments were inevitable, and will still come until I have fought the battle which every great artist has had to fight since time began. This – dimly felt while I was doubtful of my own vocation and powers – is clear as the sun to me now that I know, through the fiercest tests of life, that I am in soul, and shall be in life and utterance, a great poet.

“The philosophy of my disappointments is, that there is so much cleverness standing betwixt me and the public . . . Richard Wagner is sixty years old and over, and one-half of the most cultivated artists of the most cultivated art-land, quoad music, still think him an absurdity. Says Schumann in one of his letters: ‘The publishers will not listen to me for a moment’; and dost thou not remember Schubert, and Richter, and John Keats, and a sweet host more?

“Now this is written because I sit here in my room daily, and picture thee picturing me worn, and troubled, or disheartened; and because I do not wish thee to think up any groundless sorrow in thy soul. Of course I have my keen sorrows, momentarily more keen than I would like any one to know; but I thank God that in a knowledge of Him and of myself which cometh to me daily in fresh revelations, I have a steadfast firmament of blue, in which all clouds soon dissolve. I have wanted to say this several times of late, but it is not easy to bring one’s self to talk so of one’s self, even to one’s dearer self.

“Have then . . . no fears nor anxieties in my behalf; look upon all my disappointments as mere witnesses that art has no enemy so unrelenting as cleverness, and as rough weather that seasons timber. It is of little consequence whether I fail; the I in the matter is a small business: ‘Que mon nom soit flétri, que la France soit libre!‘ quoth Danton; which is to say, interpreted by my environment: Let my name perish – the poetry is good poetry and the music is good music, and beauty dieth not, and the heart that needs it will find it.”

Having now given sacredly to art what vital forces his will could command, he devoted himself, with an intense energy, to the study of English literature, making himself a master of Anglo-Saxon and early English texts, and pursuing the study down to our own times. He read freely, also, and with a scholar’s nice eagerness, in further fields of study, but all with a view to gathering the stores which a full man might draw from in the practice of poetic art; for he had that large compass which sees and seeks truths in various excursions, and no field of history, or philology, or philosophy, or science found him unsympathetic. The opportunity for these studies opened a new era in his development, while we begin to find a crystallization of that theory of formal verse which he adopted, and a growing power to master it. To this artistic side of poetry he gave, from this time, very special study, until he had formulated it in his lectures in the Johns Hopkins University, and in his volume “The Science of English Verse.”

But from this time the struggle against his fatal disease was conscious and constant. In May, 1874, he visited Florida under an engagement to write a book for distribution by a railroad company. Two months of the summer were spent with his family at Sunnyside, Ga., where “Corn” was written. This poem, published in Lippincott’s Magazine, was much copied, and made him known to many admirers. No one of these was of so much value to him as Bayard Taylor, at whose suggestion he was chosen to write the cantata for the opening of the Centennial Exposition at Philadelphia, and with whom he carried on a correspondence so long as Mr. Taylor lived. To Mr. Taylor he owed introductions of value to other writers, and for his sympathy and aid his letters prove that he felt very grateful. In his first letter to Mr. Taylor, written August 7, 1875, he says:

“I could never describe to you what a mere drought and famine my life has been, as regards that multitude of matters which I fancy one absorbs when one is in an atmosphere of art, or when one is in conversational relation with men of letters, with travellers, with persons who have either seen, or written, or done large things. Perhaps you know that, with us of the younger generation in the South since the war, pretty much the whole of life has been merely not dying.”

The selection of Mr. Lanier to write the Centennial Cantata first brought his name into general notice; but its publication, in advance of the music by Dudley Buck, was the occasion of an immense amount of ridicule, more or less good-humored. It was written by a musician to go with music under the new relations of poetry to music brought about by the great modern development of the orchestra, and was not to be judged without its orchestral accompaniment. The criticism it received pained our poet, but did not at all affect his faith in his theories of art. To his father he wrote from New York, May 8, 1876:

“My experience in the varying judgments given about poetry . . . has all converged upon one solitary principle, and the experience of the artist in all ages is reported by history to be of precisely the same direction. That principle is, that the artist shall put forth, humbly and lovingly, and without bitterness against opposition, the very best and highest that is within him, utterly regardless of contemporary criticism. What possible claim can contemporary criticism set up to respect – that criticism which crucified Jesus Christ, stoned Stephen, hooted Paul for a madman, tried Luther for a criminal, tortured Galileo, bound Columbus in chains, drove Dante into a hell of exile, made Shakspere write the sonnet, ‘When in disgrace with fortune and men’s eyes,’ gave Milton five pounds for ‘Paradise Lost,’ kept Samuel Johnson cooling his heels on Lord Chesterfield’s doorstep, reviled Shelley as an unclean dog, killed Keats, cracked jokes on Glück, Schubert, Beethoven, Berlioz, and Wagner, and committed so many other impious follies and stupidities that a thousand letters like this could not suffice even to catalogue them?”

Since first coming to the North in September, 1873, Mr. Lanier had been separated from his family. The two happy months with them after his visit to Florida was followed by several other briefer visits. The winters of 1874-75 and 1875-76 found him still in Baltimore, playing at the Peabody, pursuing his studies and writing the “Symphony,” the “Psalm of the West,” the “Cantata,” and some shorter poems, with a series of prose descriptive articles for Lippincott’s Magazine. In the summer of 1876 he called his family to join him at West Chester, Pa. This was authorized by an engagement to write the Life of Charlotte Cushman. The work was begun, but the engagement was broken two months later, owing to the illness of the friend of the family who was to provide the material from the mass of private correspondence.

Following this disappointment a new cold was incurred, and his health became so much impaired that in November the physicians told him he could not expect to live longer than May, unless he sought a warmer climate. About the middle of December he started with his wife for the Gulf coast, and visited Tampa, Fla., gaining considerable benefit from the mild climate. In April he ventured North again, tarrying through the spring with his friends in Georgia; and, after a summer with his own family in Chadd’s Ford, Pa., a final move was ventured in October to Baltimore as home. Here he resumed his old place in the Peabody orchestra, and continued to play there for three winters.

The Old English studies which he had pursued with such deep delight, he now put to use in a course of lectures on Elizabethan Verse, given in a private parlor to a class of thirty ladies. This was followed by a more ambitious “Shakspere Course” of lectures in the smaller hall of the Peabody Institute. The undertaking was immensely cheered on and greatly praised, but was a financial failure. It opened the way, however, to one of the chiefest delights of his life, his appointment as lecturer on English literature for the ensuing year at the Johns Hopkins University. After some correspondence on the subject with President Gilman, he received notice on his birthday, 1879, of his appointment, with a salary attached (it may be mentioned), which gave him the first income assured in any year since his marriage. This stimulated him to new life, for he was now barely able to walk after a severe illness and renewed hemorrhage.

The last two years had been more fruitful in verse than any that had gone before, as he had now acquired confidence in his view of the principles of art. In 1875 he had written:

“In this little song [‘Special Pleading’] I have begun to dare to give myself some freedom in my own peculiar style, and have allowed myself to treat words, similes, and metres with such freedom as I desired. The result convinces me that I can do so now safely.”

Among his poems of this period may be mentioned “A Song of the Future,” “The Revenge of Hamish,” and – what are excellent examples of the kind of art of which he had now gained command – “The Song of the Chattahoochee,” and “A Song of Love.” It was at this time that he wrote “The Marshes of Glynn,” his most ambitious poem thus far, and one which he intended to follow with a series of “Hymns of the Marshes,” which he left incomplete.

The summer of 1879 was spent at Rockingham Springs, Va., and here, in six weeks, was begun and finished his volume, “Science of English Verse.” Another severe illness prostrated him in September, but the necessity of work allowed no time for such distractions. In October he opened three lecture courses in young ladies’ schools; and through the winter, notwithstanding a most menacing illness about January 1st, he was in continuous rehearsals and concerts at the Peabody, and besides miscellaneous writings and studies, gave weekly ten lectures upon English literature, two of them public at the University, two to University classes, and the remaining six at private schools. The University public lectures upon English Verse, more especially Shakspere’s, in part contained, and in part were introductory to, “The Science of English Verse.”

The final consuming fever opened in May, 1880. In July he went with Mrs. Lanier and her father to West Chester, Pa., where a fourth son was born in August. Unable to bear the fall climate, he returned, alone, early in September to his Baltimore home.

This winter brought a hand-to-hand battle for life. In December he came to the very door of death. Before February he had essayed the open air to test himself for his second University lecture course. His improvement ceased on that first day of exposure. Nevertheless, by April he had gone through the twelve lectures (there were to have been twenty), which were later published under the title “The English Novel.” A few of the earlier lectures he penned himself; the rest he was obliged to dictate to his wife. With the utmost care of himself, going in a closed carriage and sitting during his lecture, his strength was so exhausted that the struggle for breath in the carriage on his return seemed each time to threaten the end. Those who heard him listened with a sort of fascinated terror, as in doubt whether the hoarded breath would suffice to the end of the hour.

It was in December of this winter, when too feeble to raise his food to his mouth, with a fever temperature of 104 degrees, that he pencilled his last and greatest poem, “Sunrise,” one of his projected series of the “Hymns of the Marshes.” It seemed as if he were in fear that he would die with it unuttered.

At the end of April, 1881, he made his last visit to New York, to complete arrangements with Charles Scribner’s Sons for the publication of other books of the King Arthur series. But in a day or two aggravated illness compelled his wife to join him, and his medical adviser pronounced tent-life in a pure, high climate to be the last hope. His brother Clifford was summoned from Alabama to assist in carrying out the plans for encamping near Asheville, N. C., whither the brothers went soon after the middle of May. By what seemed a hopeful coincidence he was tendered a commission to write an account of the region in a railroad interest, as he had done six years before with Florida. This provided a monthly salary, which was to be the dependence of himself and family. The materials for this book were collected, and the book thoroughly shaped in the author’s mind when July ended; but his increasing anguish kept him from dictating, often from all speech for hours, and he carried the plan away with him.

A site was chosen on the side of Richmond Hill, three miles from Asheville. Clifford returned to Alabama, after seeing the tents pitched and floored, and Mrs. Lanier came with her infant to take her place as nurse for the invalid. Early in July Mr. Lanier the father, with his wife, joined them in the encampment. As the passing weeks brought no improvement to the sufferer he started, August 4th, on a carriage journey across the mountains with his wife, to test the climate of Lynn, Polk County, N. C. There a deadly illness attacked him. No return was possible, and Clifford was summoned by telegraph, and assisted his father in removing the encampment to Lynn. Deceived by hope, and pressed by business cares, Clifford went home August 24th, and the father and his wife five days later, expecting to return soon. Mrs. Lanier’s own words, as written in the brief “annals” of his life furnished me, will tell the end:

“We are left alone” (August 29th) “with one another. On the last night of the summer comes a change. His love and immortal will hold off the destroyer of our summer yet one more week, until the forenoon of September 7th, and then falls the frost, and that unfaltering will renders its supreme submission to the adored will of God.”

So the tragedy ended, the manly struggle carried on with indomitable resolution against illness and want and care. Just when he seemed to have conquered success enough to assure him a little leisure to write his poems, then his feeble but resolute hold upon earth was exhausted. What he left behind him was written with his life-blood. High above all the evils of the world he lived in a realm of ideal serenity, as if it were the business of life to conquer difficulties.

This is not the place for an essay on the genius of Sidney Lanier. It is enough to call attention to some marked points in his character and work.

He had more than Milton’s love for music. He sung like a bard to the accompaniment of a harp. He lived in sweet sounds: forever conscious of a ceaseless flow of melody which, if resisted for awhile by business occupations, would swell again in its natural current and break at his bidding into audible music.

We have the following recognition of his genius from Asger Hamerik, his Director for six years in the Peabody Symphony Orchestra of Baltimore:

“To him as a child in his cradle Music was given: the heavenly gift to feel and to express himself in tones. His human nature was like an enchanted instrument, a magic flute, or the lyre of Apollo, needing but a breath or a touch to send its beauty out into the world. It was indeed irresistible that he should turn with those poetical feelings which transcend language to the penetrating gentleness of the flute, or the infinite passion of the violin; for there was an agreement, a spiritual correspondence between his nature and theirs, so that they mutually absorbed and expressed each other. In his hands the flute no longer remained a mere material instrument, but was transformed into a voice that set heavenly harmonies into vibration. Its tones developed colors, warmth, and a low sweetness of unspeakable poetry; they were not only true and pure, but poetic, allegoric as it were, suggestive of the depths and heights of being and of the delights which the earthly ear never hears and the earthly eye never sees. No doubt his firm faith in these lofty idealities gave him the power to present them to our imaginations, and thus by the aid of the higher language of Music to inspire others with that sense of beauty in which he constantly dwelt.

“His conception of music was not reached by an analytic study of note by note, but was intuitive and spontaneous; like a woman’s reason: he felt it so, because he felt it so, and his delicate perception required no more logical form of reasoning.

“His playing appealed alike to the musically learned and to the unlearned – for he would magnetize the listener; but the artist felt in his performance the superiority of the momentary living inspiration to all the rules and shifts of mere technical scholarship. His art was not only the art of art, but an art above art.

“I will never forget the impression he made on me when he played the flute-concerto of Emil Hartmann at a Peabody symphony concert, in 1878: his tall, handsome, manly presence, his flute breathing noble sorrows, noble joys, the orchestra softly responding. The audience was spellbound. Such distinction, such refinement! He stood, the master, the genius.”

In the one novel which he wrote at the age of twenty-five, he makes one of his characters say:

“To make a home out of a household, given the raw materials – to wit, wife, children, a friend or two, and a house – two other things are necessary. These are a good fire and good music. And inasmuch as we can do without the fire for half the year, I may say music is the one essential.” “Late explorers say they have found some nations that have no God; but I have not read of any that had no music.” “Music means harmony, harmony means love, love means – God!”

The theoretical relation between music and poetry would hardly have attracted his study had it not been that his mind was as truly philosophically and scientifically accurate, as it was poetically sensuous and imaginative. In a letter to Mr. E. C. Stedman he complained that “in all directions the poetic art was suffering from the shameful circumstance that criticism was without a scientific basis for even the most elementary of its judgments.”

Although the work was irksome to him, he could not go on writing at hap-hazard, trusting to his own mere taste to decide what was good, until he had settled for himself scientifically what are the laws of poetical construction. This accounts for his exposition of the laws of beauty in that unique work, “The Science of English Verse,” which was based on Dante’s thought, “The best conceptions cannot be save where science and genius are.” The book is chiefly taken up with a discussion of rhythm and tone-color in verse; and it is well within the truth to say that it is the most complete and thorough original investigation of the formal element in poetry in existence. The rhythm he treated as the marking of definite time measurements, which could be indicated by bars in musical notation, having their regular time and their regular number of notes, with their proper accent. To this time measurement Mr. Lanier gave the preeminence which Coleridge and other writers have given to accent. He conceived of a line of poetry as consisting of a definite number of bars (or feet), each bar containing, in dactylic metre, three equal “eighth notes,” of which the first is accented, or in iambic metre (which has the same “triple” time), of one “eighth note,” and one “quarter note,” with the accent on the second. Thus the accented syllable is not necessarily “longer” than the unaccented, except as the rhythm happens to make it so. This idea is very fully developed and with great wealth of curious Old English illustrations. Under the designation of “tone-color” he treats very suggestively of rhyme, alliteration, and vowel and consonant distribution, showing how the recurrence of euphonic vowels and consonants secures that rich variety of tone-color which music gives in orchestration. The work thus breaks away from the classic grammarian’s tables of trochees and anapæsts, and discusses the forms of poetry in the terms of music; and of both tone-color and of rhythm he would say, in the words of old King James, “the very touch-stone whereof is music.”

Illustrations of these technical beauties of musical rhythm, and vowel and consonant distribution, abound in Lanier’s poetry. Such is the “Song of the Chattahoochee,” which deserves a place beside Tennyson’s “Brook.” It strikes a higher key, and is scarcely less musical. Such passages are numerous in his “Sunrise on the Marshes,” as in the lines beginning,

“Not slower than majesty moves,”

or the other lines beginning,

“Oh, what if a sound should be made!”

These investigations in the science of verse bore their fruit especially in the poems written during the last three or four years of his life, when his sense of the solemn sacredness of Art became more profound, and he acquired a greater ease in putting into practice his theory of verse. And this made him thoroughly original. He was no imitator either of Tennyson or of Swinburne, though musically he is nearer to them than to any others of his day. We constantly notice in his verse that dainty effect which the ear loves, and which comes from deft marshalling of consonants and vowels, so that they shall add their suppler and subtler reinforcement to the steady infantry tramp of rhythm. Of this delicate art, which is much more than mere alliteration, which is concerned with dominant accented vowels as well as consonants, with the easy flow of liquids and fricatives, and with the progressive opening or closing of the organs of articulation, the laws are not easy to formulate, but examples abound in Lanier’s poems.

Mr. Stedman, poet and critic, raises the question whether Lanier’s extreme conjunction of the artistic with the poetic temperament, which he says no man has more clearly displayed, did not somewhat hamper and delay his power of adequate expression. Possibly, but he was building not for the day, but for time. He must work out his laws of poetry, even if he had almost to invent its language; for to him was given the power of analysis as well as of construction, and he was too conscientious to do anything else than to find out what was best and why, and then tell and teach it as he had learnt it, even if men said that his late spring was delaying bud and blossom.

But it would be a great mistake to find in Lanier only, or chiefly, the artist. He had the substance of poetry. He possessed both elements, as Stedman says, “in extreme conjunction.” He overflowed with fancy. His imagination needed to be held in check. This was recognized in “Corn,” and appears more fully in “The Symphony,” the first productions which gave him wide recognition as a poet. Illustrations too much abound to allow selection.

And for the substance of invention there needed, in Lanier’s judgment, large and exact knowledge of the world’s facts. A poet must be a student of things, truths, and men. His own studies were wide and his scholarship accurate. He did not believe that art comes all by instinct, without work. In one of his keen criticisms of poets he said of Edgar A. Poe, whom he esteemed more highly than his countrymen are wont to do: “The trouble with Poe was, he did not know enough. He needed to know a good many more things in order to be a great poet.” Lanier had “a passion for the exact truth,” and all of it.

The intense sacredness with which Lanier invested Art held him thrall to the highest ethical ideas. To him the most beautiful thing of all was Right. He loved the words, “the beauty of holiness,” and it pleased him to reverse the phrase and call it “the holiness of beauty.” When one reads Lanier, he is reminded of two writers, Milton and Ruskin. More than any other great English authors they are dominated by this beauty of holiness. Lanier was saturated with it. It shines out of every line he wrote. It is not that he never wrote a maudlin line, but that every thought was lofty. That it must be so was a first postulate of his Art. Hear his words to the students of Johns Hopkins University:

“Let any sculptor hew us out the most ravishing combination of tender curves and spheric softness that ever stood for woman; yet if the lip have a certain fulness that hints of the flesh, if the brow be insincere, if in the minutest particular the physical beauty suggest a moral ugliness, that sculptor – unless he be portraying a moral ugliness for a moral purpose – may as well give over his marble for paving-stones. Time, whose judgments are inexorably moral, will not accept his work. For, indeed, we may say that he who has not yet perceived how artistic beauty and moral beauty are convergent lines which run back into a common ideal origin, and who therefore is not afire with moral beauty just as with artistic beauty – that he, in short, who has not come to that stage of quiet and eternal frenzy in which the beauty of holiness and the holiness of beauty mean one thing, burn as one fire, shine as one light within him he is not yet the great artist.”

And he returns to the theme:

“Can not one say with authority to the young artist, whether working in stone, in color, in tones, or in character-forms of the novel: So far from dreading that your moral purpose will interfere with your beautiful creation, go forward in the clear conviction that unless you are suffused – soul and body, one might say – with that moral purpose which finds its largest expression in love; that is, the love of all things in their proper relation; unless you are suffused with this love, do not dare to meddle with beauty; unless you are suffused with beauty, do not dare to meddle with love; unless you are suffused with truth, do not dare to meddle with goodness; in a word, unless you are suffused with truth, wisdom, goodness, and love, abandon the hope that the ages will accept you as an artist.”

Thus was it true, as was said of his work by his associate, Dr. Wm. Hand Browne, that “one thread of purpose runs through it all. This thread is found in his fervid love for his fellow-men, and his never ceasing endeavors to kindle an enthusiasm for beauty, purity, nobility of life, which he held it the poet’s first duty to teach and to exemplify.” And so there came into his verse a solemn, worshipful element, dominating it everywhere, and giving loftiness to its beauty. For he was the democrat whom he described in contrast to Whitman’s mere brawny, six-footed, open-shirted hero, whose strength was only that of the biceps:

“My democrat, the democrat whom I contemplate with pleasure, the democrat who is to write or to read the poetry of the future, may have a mere thread for his biceps, yet he shall be strong enough to handle hell; he shall play ball with the earth; and albeit his stature may be no more than a boy’s, he shall still be taller than the great redwoods of California; his height shall be the height of great resolution, and love, and faith, and beauty, and knowledge, and subtle meditation; his head shall be forever among the stars.”

This standard he could not forget in his judgments of artists. There was something in Whitman which “refreshed him like harsh salt spray,” but to Whitman’s lawlessness of art he was an utter foe. We find it written down in his notes:

“Whitman is poetry’s butcher. Huge raw collops slashed from the rump of poetry, and never mind gristle – is what Whitman feeds our souls with.”

“As near as I can make it out, Whitman’s argument seems to be, that, because a prairie is wide, therefore debauchery is admirable, and because the Mississippi is long, therefore every American is God.”

So he says of Swinburne:

“He invited me to eat; the service was silver and gold, but no food therein save pepper and salt.”

And of William Morris:

“He caught a crystal cupful of the yellow light of sunset, and persuading himself to dream it wine, drank it with a sort of smile.”

Though not what would be called a religious writer, Lanier’s large and deep thought took him to the deepest spiritual faiths, and the vastness of Nature drew him to a trust in the Infinite above us. Thus, his young search after God and truth brought him into the membership of the Presbyterian Church while at Oglethorpe College; and though in after years his creed became broader than that imposed by the Church he had joined on its clergy, he could not outgrow the simple faith and consecration which are all it requires of its membership. His college notebook records his earnestness;

“Liberty, patriotism, and civilization are on their knees before the men of the South, and with clasped hands and straining eyes are begging them to become Christians.”

How naturally his large faith in God finds expression in his “Marshes of Glynn;” or his reverent discipleship of the great Artist and Master in his “Ballad of the Trees and the Master,” or his “The Crystal,” which was Christ. Yet, with not a whit less of worshipfulness and consecration, there grew in him a repugnance to the sectarianism of the Churches which put him somewhat out of sympathy with their formal organizations. He wrote, in what may have been a sketch for a poem:

“I fled in tears from the men’s ungodly quarrel about God. I fled in tears to the woods, and laid me down on the earth. Then somewhat like the beating of many hearts came up to me out of the ground; and I looked and my cheek lay close to a violet. Then my heart took courage, and I said:

‘I know that thou art the word of my God, dear Violet:

And Oh, the ladder is not long that to my heaven leads.

Measure what space a violet stands above the ground;

‘Tis no further climbing that my soul and angels have to do than that.’ “

It was this quality, high and consecrate, as of a palmer with his vow, this knightly valiance, this constant San Greal quest after the lofty in character and aim, this passion for Good and Love, which fellows him rather with Milton and Ruskin than with the less sturdily built poets of his day, and which puts him in sharpest contrast with the school led by Swinburne – with Rossetti and Morris as his followers hard after him – a school whose reed has a short gamut, and plays but two notes, Mors and Eros, hopeless death and lawless love. But poetry is larger and finer than they know. Its face is toward the world’s future; it does not maunder after the flower-decked nymphs and yellow-skirted fays that have forever fled – and good riddance – their haunted springs and tangled thickets. It can feed on its growing sweet and fresh faiths, but will draw foul contagion from the rank mists that float over old and cold fables. For all knowledge is food, as faith is wine, to a genius like Lanier. A poet genius has great common sense. He lives in to-day and to-morrow, not in yesterday. Such men were Shakspere and Goethe. The age of poetry is not past; there is nothing in culture or science hostile to it. Milton was one of the world’s great poets, but he was the most cultured and scholarly and statesmanlike man of his day. He was no dreamer of dead dreams. Neither was Lanier a dreamer. He came late to the opportunity he longed for, but when he came to it he was a tremendous student, not of music alone, but of language, of philosophy, and of science. He loved science. He was an inventor. He had all the instincts and ambitions of this nineteenth century. But that only made his range of poetic thought wider as his outlook became larger. The world is opening to the poet with every question the crucible asks of the elements, with every spectrum the prism steals from a star. The old he has and all the new.

All this a man of Lanier’s breadth understood fully, for he had a large capacity and he sought a full equipment. Perhaps the most remarkable feature of his gifts was their complete symmetry. It is hard to tell what register of perception, or sensibility, or wit, or will was lacking. The constructive and the critical faculties, the imaginative and the practical, balanced each other. His wit and humor played upon the soberer background of his more recognized qualities. The artist’s withdrawn vision was at any need promptly exchanged for the exercise of that scrupulous exactitude called for in the routine of the law-office or the post-office clerkship or other business relations, or for the play of those energies exerted in camp or field. There, so his comrades testify, the most wearing drudgeries of a soldier’s life were always undertaken with notable alacrity and were thoroughly discharged, when he would as invariably return, the task being done, to the gentle region of his own high thoughts and the artist’s realm of beauty.

But how short was his day, and how slender his opportunity! From the time he was of age he waged a constant, courageous, hopeless fight against adverse circumstance for room to live and write. Much very dear, and sweet, and most sympathetic helpfulness he met in the city of his adoption, and from friends elsewhere, but he could not command the time and leisure which might have lengthened his life and given him opportunity to write the music and the verse with which his soul was teeming. Yet short as was his literary life, and hindered though it were, its fruit will fill a large space in the garnering of the poetic art of our country.