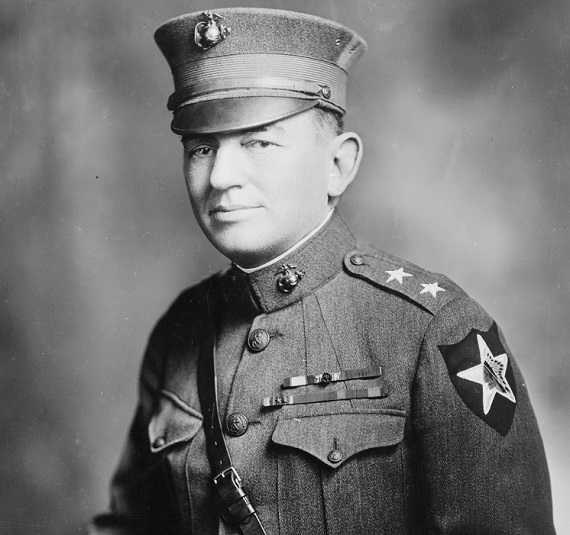

A review of The Greatest of All Leathernecks (LSU Press, 2019) by Joseph Simon.

Anyone who has spent any amount of time in eastern North Carolina along the Atlantic shore or was blessed to wear the insignia of the United States Marines is well-aware of the name John A. Lejeune. In this biography by Joseph Simon we are introduced to the history, background, and legacy surrounding the man who made the modern Marine Corps. The work follows a largely chronological pattern from Lejeune’s time growing up on a post-war plantation in Reconstruction ravaged Louisiana in the 1860’s and 1870’s to his days in the Great War and later time as Commandant where he would change not only the Marines and their place in American life, but the entire United States military for a generation. To give an example, if you have ever seen a recruiting poster with a hard-looking Marine, or a television commercial advocating “the Few, the Proud, the Marines” you can thank Lejeune. His effect was wide-ranging and profound. Lejune’s early childhood on the shores of the Mississippi River shaped who he would become as he brought victory at Blanc Mont and re-organized the Marine Corps from sea-going bellhops to the most elite amphibious force the world has ever seen.

However, before we get into that let us get some of the formalities of book review out of the way, the brass tacks that a reader really wants to know before shelling out hard-earned cash for mental stimulus. First of all, if you are a Marine Corps veteran (as I am) then this book is like catnip. Every page is a reminder why you were blessed to step on the yellow footprints at Parris Island or San Diego (both of which exist today because of Lejeune’s leadership as Commandant in the 1920’s). Have no immediate personal connection to the Corps? Not a problem as Simon does an excellent job of laying out the political machinations of the period of American history in which Lejeune operated. This is one place where the author has absolutely done his homework. While the book is hamstrung by the presence of endnotes, it is very-well researched and is a credit to Simon’s labors.

Some knowledge of American foreign policy between Presidents McKinley to Hoover would help before picking up the book, but it is not a deal breaker as the author gives enough to detail to help situate the reader in the right frame of reference. One drawback is that sometimes the author will backtrack to an earlier point in Lejeune’s career without immediately letting the reader know that a flashback is occurring. There are also some minor typos, but all things considered this is a very helpful and learned presentation of an important Southern leader in American military history.

And Lejune wouldn’t be Lejune without the South.

Descending from Acadian refugees like many other French-Louisianans, Lejeune’s family had a long history of not only military service, but a record which distinguished them in areas of bravery, wisdom, and leadership. His great-grandfather was a French and Indian War veteran who lived to the age of 105, only dying because he fell off his horse after visiting the dentist for a tooth extraction. Lejeune’s father, Ovide, would bravely serve the South in the First Louisiana Regiment of Cavalry, fighting in many early battles before health required him to return home to the plantation. Yet, as is the case with many young Southern men, it was John Lejeune’s mother, Laura Archer Turpin, also of French ancestry, who became central to the leader and scholar young John would become.

After the War there were no schools or other available means of education (John A. Lejeune was born January 10, 1867), so Mrs. Lejeune took it upon herself to found the Lejeune School and taught children, of all backgrounds, the basics of Reading, Writing, and Arithmetic. Lejeune would look back at these days as the solid foundation that allowed him to excel at Louisiana State University in Baton Rouge and later at the U.S. Naval Academy in Annapolis, Maryland. But, that is not the only education John would receive at home. His father insisted he learned the exploits of Nathan Bedford Forrest, under whom John’s uncle had served and died, and his father’s hero Robert E. Lee. Lee’s published early recollections were a bedside favorite of Ovide’s to read to young John. Ironically, Lejeune would follow Lee’s footsteps in retirement after his Marine Corps career in moving to Lexington, Virginia, and taking on the superintendence of the other school in town, the Virginia Military Institute. There is no question that the illuminating and instructive lessons from the military heroes of the Confederate Army played a large role in John A. Lejeune’s desire to serve his country, much like his father. It is worth noting at this point that Ovide Lejenue opposed secession, but where Louisiana went he was keen to follow. This homespun example of duty most assuredly made an impression as the future Marine Corps leader grew in stature and knowledge. More importantly, Simon describes in great detail how Lejune’s mother and father encouraged John to remember the most important kind of wisdom, faith in Christ and obedience to God. His mother Laura was the daughter of a Presbyterian minister, and Lejune’s parents were regular and faithful adherents at St. Stephen’s Episcopal Church, the only Protestant church in the parish. John A. Lejeune remained a devout Christian his entire life.

Much can be learned from Lejeune’s life and career. His determination and skill, earned from a hardy life of work in the fields and levees of Point Coupee Parish and groomed by his Southern background, is inspirational for any young boy, Southern or not. If any man deserves the title “The Greatest of All Leathernecks” it is most certainly, John Archer Lejeune.