A review of The World They Made Together, Black and White Values in Eighteenth Century Virginia, by Mechal Sobel, Princeton University Press, Princeton, New Jersey, 1987

I

In America, in 1607 the first successful British settlement began in a land they called Virginia. Within a few decades another people began arriving, taken from their homes in Africa. Both peoples arrived imbued with the culture of their homeland. This book is a partial but substantial rendering how two very different peoples, also two different racial composites, learned to survive and achieve together in the Virginia wilderness during the 18th century.

The intertwining began slowly in the 17th century and became consummate in the 18th. They were mixing their cultures intimately to become together a singular people called Virginians. By the end of the century they would lead a new nation. And though the names of the leaders were in every instance British, the blood and cultures of these once very separate peoples had so interwoven by the end of the 18th century that no one can say the British would have succeeded so well or so thoroughly without the Africans.

The people from the British Isles were Caucasian. They came to Virginia free, with a sense of risk, adventure and a yearning for their own economic success and sometimes their own religious expression. They were happy to be British and in the early to mid decades of the 18th century were very content to be British.

The people from Africa were mostly from the western African lands, Negro, and overwhelmingly taken by force from their homeland, transported in chains to be sold as personal property to whoever would pay the price. They were not the first Africans shipped to the new and large continents called North and South America along with the islands in the Atlantic. But to Virginia in the 17th century fewer came. When they did, only the wealthiest men could purchase them. It was in the 18th century these two peoples became recognizable to themselves and others as a new breed of people.

While from different continents and speaking different languages, as the Virginia population of both races grew and their economy grew, their practices of property, religion, ownership of land and people and family, overlapped and mutually absorbed one another. They intermingled, struggled to develop the resources of Virginia and eventually created a most prosperous economy that lasted till the invasion of their land in 1861. Though in the 18th century enticed by the British Crown to turn against the new United States, Black Americans, where allowed, fought bravely against the British Empire to gain independence for their new country.

************

These new Virginians were different from other people in the known world. Even within America, the land that was to become the United States, they were a people with a singular blend of bi-racial beliefs girding their economy, religion, government and family.

Whether in today’s world we want to hear this story or just disbelieve it, it happened. Together these White and Black people who could not speak to one another in the beginning developed a language with phrasing from both cultures, and from daily practices that were dependent on the land and their own place under the sun.

Most importantly they shared their religious and spiritual natures. They worshipped together, lived close and intimately together, often in the same house, worked the same lands. Virginia became a standard for later colonies and eventually the States where Virginians Black and White moved for greater prosperity. The idea of an economic Empire bloomed at the outset in America.

It is false to believe this new people existed in the Northern colonies in America and later the United States. Though slavery was entwined in the Northern colonies and they helmed the Slave Trade and initially built their economies on that Trade, the mingling of cultures and blood was far less frequent or intense. To be truthful, though the Northern and Southern colonies were populated and governed by peoples from the British Isles, the cultures they brought with them were different from one another. It was true in politics but especially in their spiritual values.

The North as a region never assimilated the African people. Long into the War of 1861 and later the North looked to find ways to be rid of them. In truth, they feared and often hated Black people. They refused to live with them, shunned them and when they did abolish slavery inside their colonies (though not the Slave Trade which remained theirs exclusively as before), they sold their slaves to southern States rather than make a place for them in northern society.

II

Mechal Sobel wrote this book 30 years ago. It is as valid today as then. The book is not a theory. It is a correlation of fact to fact. It demonstrates how patterns of living and beliefs from the British Isles and western Africa mingled, effected and merged the lives of White and Black Americans in Virginia. These facts and patterns lay in the stories the people told one another.

Stories are the medium of culture. They weave the past into our present and give us markers for our future. They instruct the young and reinforce the old. They make it possible to understand what we have not yet experienced and to grasp the past we cannot experience. They become the circumference of our lives where our ancestors and our posterity co-exist. They remind us of the treasures of our affections and dreams and bind us to the suffering of those who wanted a better world for us.

Sobel’s achievement is to delineate the threads of white and black America as they exchanged cultures to create a new one that held them together. It’s not an unusual story. It is the recurring story of different peoples learning to get along to survive. They each had their differing history and beliefs – their own stories – the remembrances and practices from their original lands of architecture, food, family, and religion, even slave/master relationships governed their approach to surviving in the new frontier of 18th Century Virginia. Oddly perhaps, or not so oddly, some Africans were slaves or slaveholders in Africa and had already a sense of the relationships possible between slave and master.

Parcel to understanding the possibility how this could be done, we need to accept something they knew: they always saw and accepted the humanity in eachother. They lacked hatred for one another. Not in Virginia (nor the other Southern colonies) did the White people ever hate Black people. Their spiritual beliefs forbade it. Their emotions were a mixture of fear and affection because while living closely, even intimately hand to hand, they could find no way out of the slavery economy (except to act individually). (While Whites did not become slaves, Blacks did from at least the middle of the 17th century become Masters. A Free Black population existed certainly from mid-17th century, maybe before.) The people lived and worked and played and prayed together. Unlike industrial societies scripted to impersonal finances and separate, interchangeable, disposable cogs of humanity, agrarian societies create a human bond tied to the rhythms of nature, a constant reminder that humanity and its endeavors require the favor of powers greater than money and machinery and even human aspiration.

***********

Sobel’s book is divided into 3 main sections: Attitudes Toward Time and Work, Attitudes Toward Space and the Natural World, Understandings of Causality and Purpose, with a final Coda that reiterates an understanding startling in today’s world. Each of the three main sections rests on its own. To explain them in a short review isn’t possible. Better to provide direct quotes that point to the substance and value of Sobel’s work. They are not a replacement for reading this book. The research is exhaustive, her writing careful and precise. The pages are a pleasure to read as you realize the author truly loves her work and prior to writing learned to swim in the waters of her research with ease and facility.

Here goes:

p. 64: “Most blacks and most whites came to Virginia with what looked like ‘lazy’ attitudes to work. They were generally slow workers, who valued changes in the working pattern and holidays. Their ‘clocks’ were work clocks, with both the day and the year tied to agriculture and not to a mechanical timepiece. Certain times had positive or negative valence for both peoples, and taboos and other traditions governed their use of time.”

p. 65: “In Virginia, the perception of time by blacks and whites of all classes changed. Over the course of the century some Virginians, including some slaves, obtained watches and clocks, but well over ninety percent of the population never had mechanical timepieces, and it is very likely that many of those who did regarded them as status symbols more than as mechanical regulators of their days. On the contrary, there is evidence that whites ‘slided over’ into black (and earlier English) attitudes toward time and work.”

p. 164: “In the Baptist and Methodist churches, blacks, together with whites, found a possibility of renewing baptismal patterns, having their names recorded, and having their marriages honored. It was there that they were once again called brother and sister in a new black and white Christian family and became members in restricted societies that had rites, rituals, taboos and charisma.”

p.165: “Old English and African attitudes toward the holiness of particular places, and the magical power inherent both in them and in spirit-workers, reinforced each other and gave root doctors, cunning men and women, and even witches an acceptable role to play.”

p. 166: “Unlike the small houses and most of the so-called Big Houses, which were often small houses in disguise, a very small percentage slaveowner homes were actually mansions built in an English tradition. The family inside these houses, however, was uniquely Southern: Blacks and whites were inside them sharing in new Afro-English traditions and creating joint families, as well as separate ones. … “By mid-century blacks and whites were in one family, by blood and by adoption, all over Virginia. They were interacting in ordinary times and at times of celebration.”

p. 166 – 167: “Blacks and whites together were ‘the vulgar and the debased’ (a description by Elkanah Watson of New England in 1787 while graveling Virginia). They were betting, shouting, fighting with each other, but they were also likely to hunt, dance, and ‘play’ together. … When the Northern tutor, Fithian, found his teenage white students dancing with the slaves, he was disturbed; but Southern whites may have been more comfortable with the practice than he was.”

p. 167: “Rites of passage often involved racially mixed groups. Blacks and whites were together at births, and christenings, weddings, deaths, and funerals.”

p. 174: “African beliefs (in Africa) about afterlife varied, but virtually all Africans believed that the spirit or spirits in men and women lived on after death … In the afterlife ‘Life continues more or less the same … as it did in this world.’ However, that world is a better place, the real ‘home’, where forefathers live on. Dying is ‘going home’.”

p. 175: “Slaves (in Africa) were outsiders. They were not generally buried with freemen, and memorials were not set up to house their souls. … It was not expected they would be in the land of the spirits.”

p. 176: “The (African) individual’s goal is self-perfection, to be made whole or to achieve ‘oneheartedness’ … ‘An African’s esteem for someone is a function of his ability to dominate his passions, emotions, behavior, and actions.’ The world to come is vouchsafed to one who has mastered himself and become whole in this life.”

p. 180: “After 1750, spiritual revival was widespread in Virginia. It began in response to the needs of the lower class, to their conflicts in values, and to their longings for coherence. Almost invariably, when it came, it came when and where whites were in extensive and intensive contact with blacks.” Emphasis in original “… Virtually all 18th century Baptist and Methodist churches were mixed churches, in which blacks sometimes preached to whites and in which whites and blacks witnessed together, and shared ecstatic experiences at ‘dry’ and wet christenings, meetings and burials. … In the 19th century, black and white churches were to go essentially separate ways, but the joint experience of the 18th century altered the world views of each. They emerged far more coherent than at the outset of the experience, with their understandings of death and afterlife changed as a result.”

p. 189: “Blacks and whites were together in virtually every new congregation in Virginia. … In this, the Baptist phase, and later in the 1770s and 1780swhen the Methodists instituted many of the same or similar practices (consensus-run communities), racially mixed groups responded, and no participant seems to have questioned seriously the propriety of these ‘promiscuous’ gatherings. White and black, male and female, new converts created new churches.”

p. 191 “Blacks and whites in one congregation had to be at peace with one another, or ‘in fellowship’. Disagreements had to be aired, and forgiveness extended by all parties. …Blacks appear in these church records as individuals, and their interaction with whites can be documents. … there is no doubt but that black opinions were being heard and counted in many matters, not only in defense of charges made against them. … Blacks were part of the covenanting ‘inner group’ that formed many of the churches, signing the covenants with their white brothers and sisters.

“Slaves did (emphasis in original) bring criticism of whites to communal sessions. It was not simply an abstract right … Baptist and later Methodist churches were ‘courts’ for their members. All issues of behavior and misbehavior were to be brought before them. … They dealt with issues between whites and whites, blacks and whites and whites and blacks (emphasis in original).

221: “… blacks were often with whites at deathbeds … Funerals for blacks were often attended by substantial numbers of whites, and funerals for whites were attended by blacks. They cried together, sang together, and experienced spirit together. Sometimes they were buried next to each other, in the same sacred place.”

p. 226: “18th century religious experiences left black and white Christians expecting to meet one another in heaven. There they would witness for one another, as they were ‘brothers and sisters in the Lord’. There, most believed that black and white redeemed would ‘live together and love one another throughout a long and happy eternity’. A shared church life had prepared them for this. The church had absorbed the goals of the early visions of the new world: the church had become the Garden of Eden.”

p. 241: “Whites had come to share many African perceptions without being aware of it. African attitudes to time and place had reinforced old Christian views, and an African esthetic had altered both building styles and techniques. Belief in magic had been reinvigorated, and it was accepted that human beings could sometimes cause death through its power. Spirits were perceived in a new way. Life after death was seen as a ‘homecoming’ and kin were expected to welcome the spirits. … In sharing day-to-day life with blacks, some whites had ‘slided over’ into their ways of working, some were influenced by their perceptions of time and space, and eventually some were unconsciously made ready to share black traditions of seeking spirit in ecstasy. …

p. 241 – 242: “Blacks and whites were together in church, house, field and garden. They had variant visions of the future, but they shared an important part of the present as well as time past. Surveying Southern culture in the 20th century, Henry Glassie has suggested that we ought to ask ourselves ‘why the children of white farmers in the Lowland South are often given carefully homemade Negro dolls with which to play.’ I think the beginning of the answer lies in the 18th century, when blacks and whites played together both as children and later before God.”

CODA

“Charlottesville

Monday Morn’g,

31 May 1824

Between 8 and 9 o’ck called on Mr. Jefferson. The boy conducted and left me at the door and I knocked. Mr. Jefferson came himself. I approached and shook hands with him and he asked me in.”

“A Book Peddler Invades Monticello”, The William and Mary Quarterly, Vol. 6, No. 4, October 1949 pp. 631 – 636, ed. William Peden

So begins the memoir notes of Samuel Whitcomb, Jr., book agent for Thomas B. Wait & Sons of Boston, Massachusetts, to ‘travel west and south’ to gather subscriptions for their books, in this case a volume (probably the final) of William Mitford’s History of Greece. Jefferson declined. He was familiar with Mitford and did not regard him highly. But then Whitcomb immediately drew Jefferson into conversation that continued upwards of an hour before Whitcomb decided it was best to leave. (The next day Whitcomb called on Madison. He writes his comparison of the two friends. Sobel doesn’t quote him about Madison, so it is left out of this review. She quotes Jefferson at p. 236)

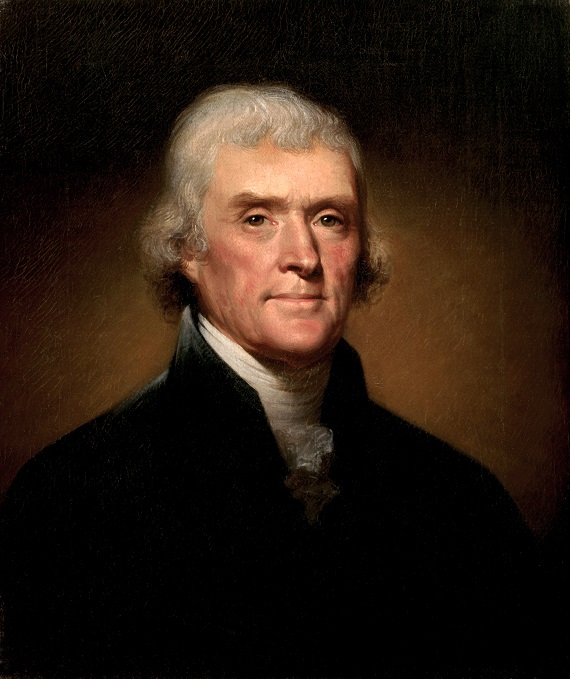

They talked of a good many things. Sobel finds interesting, and I concur, is Jefferson’s observance on the hearts of black people. He was 81. Another 26 months and he’d be gone. Through all his years he and black people lived and labored side by side. He was keenly aware of the mutuality among the white and black people of Virginia. He knew the black people’s daily lives, aptitude and fortitude, their beliefs and courage and human warmth. He was at home with black people whether they were new to Virginia or had been born after several generations in Virginia and were integral within his conjoined families, his own and his wife’s.

Jefferson appears to have understood the human longing of displaced Africans for their homeland. He has been credited with a poem in his Virginia Almanack for 1771, “Inscription for an African Slave” which makes just this point. Sobel at p. 96. Here would be his underlying acceptance, not only of the heartfelt suffering of newly arrived black people, but also for some already here down a generation or more. Jefferson understood the great storytelling culture of Africans through the generations.

Sobel writes of two black women in his household: Hannah Jefferson and Ursula Hemings. “Jefferson is known to have ordered his overseer to build the Negro houses close together so that ‘the fewer nurses may serve & that the children may be more easily attended to by the superannuated women’. He, as many slaveowners, selected sites for slave houses. For example, he wrote his overseer in Bedford County, Joel Yancey, “Maria (not Jefferson’s daughter Maria) having now a child, I promised her a house to be built this winter, be so good as to have it done. Place it along the garden fence on the road Eastward from Hannah’s house.’ Jefferson’s promise was clearly given in response to a black’s request, dependent on her family status. Maria was Hannah’s sister. They no doubt wanted houses next to each other. The overseer is being ordered to do what the slave wanted.” p. 111

Hannah Jefferson was an important personage in Jefferson’s life. It may surprise us today to find a slave would approach, even admonish Jefferson about his personal salvation.

p. 215: “Once when Thomas Jefferson was ill, Hannah, of Jefferson’s black family all her life and caretaker at his retreat at Poplar Forest, wrote him a simple but powerful message:

‘I heard that you did not expect to come up this fall I was sorry to hear that you are so unwell you could not come it grieve me many time but I hope as you have been so blessed in this that you considered it was God that done it and no other one we all ought to be thankful for what he has done for us we ought to serve and obey his commandments that you may set to win the prize and after glory run Master I do not (know that) my ignorant letter will be much encouragement to you as knows I am a poor ignorant creature … adieu, I am your humble servant

Hannah’

“Here Hannah was preaching to Thomas Jefferson, and her message is clear:

God sent your illness.

This illness is a blessing that can lead to your conversion.

You can act to achieve conversion. (You have not been following the commandments!)

The ‘prize’ you will get is life everlasting.”

Hannah was not being presumptuous. She had her beliefs at heart and was going directly to another person, albeit her ‘master’, who she knew well, who was part of her family. She understood no harm would come to her for speaking forthrightly, honestly and affectionately from her deepest beliefs.

Sobel writes of Ursula Hemings, Jefferson’s daughter Martha Randolph’s nurse and nurse to all the children not in school whether Martha was at Monticello or elsewhere. The overseer wrote Ursula often took them to his home to visit, that she was the one to care for them and discipline them when they needed to be, that the children “were all very attached to her. They always called her ‘Mammy’ …” p. 136

For Virginians the ‘Mammy’ was the children’s caretaker and teacher of life and family ways, the “culture arbiter” about whom Sobel quotes Eugene Genovese: “It was they who imparted the speech of the quarters to the children of the Big House, who introduced them to black folklore, who taught them to love black music, and who helped bend their Christianity in the folkish direction the black preachers were taking it.” Sobel at 137

Ursula was married to Wormley Hemings, and, therefore, intimately within Jefferson’s merged white and black families. “The family relationships at Monticello were both much clearer and much more clouded (than Washington’s at Mount Vernon). … the Jefferson white and black families were … related by blood as well as fictively. Sally Hemings, whether she was Jefferson’s mistress or his favorite nephew’s concubine, was in the white family long before she bore children. (Emphasis in original) Daughter of Betty Hemings and John Wayles, (Sally) was Martha Wayles Jefferson’s half-sister and Thomas Jefferson’s sister-in-law. The other Hemings-Wayles were all related to the Jeffersons as well.

“In the Jefferson-Randolph-Hemings household, Ursula … was Mammy, while Sally Heming’s half-brother, John was called ‘Daddy’. (John was Betty Heming’s child … born after John Wayles had died, and his father was one of Jefferson’s white carpenters, John Nelson.) The white children were very attached to ‘Daddy’ John, visiting him often in the carpentry shop, and receiving miniature woodwork from him. Jupiter, Jefferson’s body servant, was called ‘Uncle Juba’ and was very close to the children as well. When writing to his daughter, Mary T. Eppes, in 1779, Jefferson noted that ‘Ellen (her niece) gives her love to you. She always counts you as the object of her affection after her mama and uckin (Uncle) Juba’. She put Juba before her father, her grandfather and all whites except her mother.” Sobel at 139 – 140

Jefferson’s family was a microcosm of the Virginia families at large.

*********

Jefferson had travelled much of Europe, much of America, had led both in the Revolution and the cementing of the new Constitution the States lived under. He was often gone from Monticello. Yet his black family as well as his white family had helped him all along the way, undergirding his public and private efforts by caring for his lands, his home and each other. Indeed, his black family in body and heart was his family as much as his white family. To themselves and to most Virginians, both families were one family.

But he had been exposed hardly at all to the scientific and literary talents of black people except, to some extent, Phyllis Wheatley and Benjamin Banneker. At the end of his life blacks in America were at the portal of coming into their own and would flower in the pursuits he most admired by the mid-late-19th century and thereafter.

So the startling statement Jefferson made to Samuel Whitcomb, Jr. that late May morning, 1824 is part expected, part unexpected. Whitcomb asked what he thought of Negroes and Jefferson replied with searing honesty reflecting a lifelong occupation of his mind and heart among a people that were his own people. Whitcomb wrote: “He hopes well of their minds though he has never seen evidence of genius among them, but they are possessed of the best hearts of any people in the world“. Sobel quotes the last phrase at p. 236.

This man whose humanity today America denigrates to the loss of her own humanity and, so, eventual demise if she continues, who believed as he told Whitcomb that May morning in a Supreme Being and a life after death as he wrote November 13, 1818 to John Adams on the passing of Abigail, was talking from his heart about the hearts of his family and dearest people. Like the many other Virginians bred through the 18th century, this man of circling rainbows was looking forward to continuing with them, white and black, in Heaven.