A review of Clyde Wilson, The Yankee Problem: An American Dilemma (Shotwell Press, 2016).

The Yankee Problem An American Dilemma by Clyde Wilson consists of 12 sections, four of which involve book reviews (half of them devoted to biographies of the Beecher family or the family of John Adams), four of which directly address the devilish nature of that New Englander, Anglo-Saxon type known as the Yankee (with one of them specifically focusing on John Brown and another focused on Northern nationalism), and the other four addressing, on the one hand, two authors who favored the South (James Fennimore Cooper and William Gilmore Simms) and, on the other hand, the main causes that led to the War Against The South. The longest section is 27 pages while the shortest section is merely a page, with the remaining sections being between 3 to 11 pages in length. Half of all twelve sections employ “Yankee” in their titles.

The book has the overall feel of a short collection of intimate historical conversations (with extensive overlap of content and facts from one section to another) revealing Clyde N. Wilson’s points of view not only as a historian of the South and what constitutes the Southern tradition but also as a philosopher, offering concise and emphatic evaluations filled with historical moral insight, fresh and determinative, as to what the facts really are, what America is, and what has happened to her, all written in a tone neither folksy nor academic but somewhat elegiac and eminently readable. There is a wonderful, charming, even superb simplicity and freshness to the writing throughout the book, balancing plain, direct language with nuanced and astonishing historical acumen in every section.

Showing disdain for current “scholars” and the “professional historian,” Mr. Wilson, as I say, wears his learning lightly but that observation doesn’t mean the book he wrote is light reading, however few its total number of pages. Deceptively easy to read, it grows in depth and richness on the second and third readings, without any loss in its capacity to grip and fascinate the reader.

People who think the South was just a lazy, white-trash, racist group of rednecks who fought the so-called Civil War in order to preserve slavery are not the proper audience for this book – unless they are adventurers or are healthy specimens of humanity that now and then enjoy a big dip in ice cold water, figuratively speaking. Otherwise, such Americans won’t like this book. Although it’s a physically short and small, it has big ideas in it, ideas big enough to blow up every falsehood conceived about the South as well as every false claim conceived by the North. It is that potent and that memorable. However, if you’re not a born Yankee, not a dedicated Blue state fanatic, or if you’re a skeptic about the “official stories” told you by government-run public schools, then you’ll find this book deceptively easy and viscerally enjoyable to read, even while every section remains jam-packed with well-cited, scintillating facts that Clyde Wilson often joins to superb philosophical evaluations from the historical perspective of the Southern tradition. For the Southerners who already know a great deal of their past, I’ll bet the knowledge Clyde Wilson’s offers here will surprise a good many of you as well.

The facts in this book themselves alone, even without Mr. Wilson’s commentary, explanations, asides, and evaluative insights, unveil a unique, riveting story about the South, exposing and destroying the mystique behind the standard Northern historian’s view of America while simultaneously making a case for the need to do a complete re-evaluation of Northern interpretations of American history because of its distortions, fabrications, and usurpation of the South’s unbroken tradition and values in and for America from the beginning of colonial times.

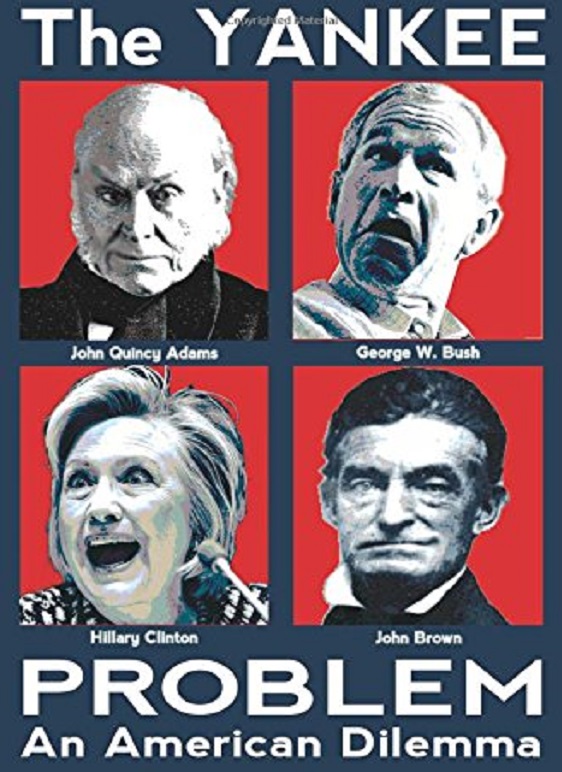

While people often tout the aphorism, “You can’t judge a book by its cover” as a false statement, such is not the case with Clyde Wilson’s tiny tome here. You can judge the book by its cover. It’s scathingly honest and directly shows up the Yankees for the foolish but despicable power-mongers they are. On the cover, the photographs of George W. Bush, a Yankee who looks like a stooge in his photo, and Hillary Clinton looking like a fanatical hysteric in hers, show hilariously and irreverently these two Yankees in their worst and clownish aspects. The same is true of the two other famous Yankees whose photos are reproduced on the cover: John Quincy Adams (“hateful and vindictive”) and John Brown (a Connecticut Yankee and looking crazed and murderous in his picture). Both of them are special targets in Mr. Wilson’s work devoting separate sections to them the better to skewer them with facts about their own behavior and in no way sparing them the condemnation that they truly deserve. The phrase, “The Yankee Problem,” are in big, inch-high white letters on the front cover as well. Never was a title more apt and more plainly valid.

Clyde Wilson states that the proper study of the period bringing on the War Between the States is Northern history because, while historians have created an industry out of explaining how the South is evil, the unanalyzed assumption in all the words written and published for more than a hundred and fifty years thus far is that the North was somehow normal and therefore the standard of all things good in America. But closer examination of that assumption is necessary since Northerners, specifically New Englanders, i.e., Yankees, erroneously believed it was they who fought the Revolution and founded American liberty for all when, in fact, up until 1850 or so, American history had always been “Southern.” In “Those People (The Yankees),” Mr. Wilson writes, “It is Yankee, not Southern, history that needs to be put under the microscope for further analysis. How did the post-Puritan North move from John Adams to John Brown and Abraham Lincoln?”

Clyde Wilson reverses and destroys the entire “American history” of the South and the war by exposing it as (only) “Yankee history” and erroneous myth making (i.e., Northern mythology).

Once upon a time, everyone knew that nine of the Presidents of the US were from the South (In fact, “nine of the first twelve Presidents were Southern plantation owners.”) Southerners fought both in the North and in the South, but no Northerner or Yankee ever volunteered to fight in the South. Up until 1850 or so, what people considered American was clearly what came from the South. Southerners were the true Americans — until the Civil War entitled the North to mutilate the South, raping it financially, physically and politically. After the war, only Yankee historians were able to get attention. Yankees had begun to become the “real Americans.”

Even ten years before the War Between the States, Mr. Wilson clearly shows that America saw itself through the eyes of Washington and Jefferson, John Randolph, Henry Clay, Daniel Morgan, Daniel Boon, Francis Marion, and identified itself with the Louisiana Purchase and the Battle of New Orleans. Up until the War, everyone understood that it was Southerners who had made the Constitution. Americans knew that Virginians had been responsible for the spread of constitutional rights, not the so-called “Puritan Fathers.” Indeed, the facts bear out the truth that it was Southerners who acquired the territory, settled the West, and fought the wars.

And truth to tell, New England had been only a denying force in America’s move forward all this time.

Washington Irving, who belonged to the early settlers of New York, made fun of Yankees in his story “The Headless Horseman.” (“Ichabod Crane was a cowardly Yankee twit from Connecticut,” writes Mr. Wilson.) James Fennimore Cooper, also not a Southerner, shared a similar dislike of Yankees in novels like Homeward Bound and Home as Found, among others, creating in them positive characters who were generous and cooperative, having no agenda to impose, seeking no power over others while his Yankee characters disparage good manners, are boastful and trendy, willing to toss tradition and reputation aside for the sake of money or the latest idea. The predatory, roguish behavior of these Yankees upon society and manners, politics and economy were bothersome to Cooper. For him, they were “pushy social climbers,” refusing to grant equality to those they viewed were less prosperous than they, and valuing education in such a superficial and presumptuous manner that no good leadership or good men and good women were obtainable through it. Its salient feature was turning people into tools, tools of obedience. For Cooper, the real business of America was individual liberty.

And even into the war, Northerners known as Copperheads blamed the conflicts arising between North and South on power-hungry, greedy New Englanders who sought to plunder America, not on the Southerners who viewed the new federal government as a means of mutual cooperation.

By their own actions, Yankees showed the world that they viewed the new government merely as a tool for satisfying their own self-interested purposes. Who but the New Englander known as John Adams sanctioned the Sedition Law to punish anti-government speech in clear violation of the Constitution? (By contrast, Jefferson’s dislike for mixing issues of church and state was integral to his dislike of New England’s power-grid of self-appointed “saints.”)

In another context, during the War of 1812, it was the Yankees who “traded with the enemy and talked openly of secession.”

And on the topic of literature, have New Englanders produced even one singular poet who didn’t fail to turn off generations of Americans over dreary little ditties from, say, Whittier or Longfellow, or even Emerson or Thoreau? No.

It was soon after the War of 1812 that Yankees became singularly aware of their miniscule status and launched a campaign as a consequence to control the idea of “America.” Marked by an unwarranted sense of superiority and possessed of an abundance of New England greed, Yankees began to build wealth by selling products in a “market from which competition had been excluded by the tariff,” making the price of cotton low, but proclaiming the low price was due to Yankee efficiency, even while the South that had been the real producer of that wealth.

Soon these successful but self-serving, crafty Yankees began consciously and deliberately to strive for dominance in the field of capturing the history of America itself by seizing control of it. For example, it was due to the efforts of New Englanders, not Southerners, that the Revolution was successful. George Washington became a prim New Englander, not the foxhunting Virginian gentleman he set out as.

Even though it was the South who developed the West, the “Massachusetts elite” took control of America’s symbols and began rejecting all competing claims such that even Western movies today, Wilson remarks, still show families from Boston moving west by covered wagon when such things never happened in reality.

Historians need to write more real history, Mr. Wilson declares, because the North has been “Yankeeized,” despite James Fennimore Cooper and Washington Irving’s efforts to ridicule the Yankees for good reasons, and to show favor to the South.

The Yankees have succeeded in creating a modern “version of self-righteous authoritarian ‘Liberalism,’” the kind exemplified by Hillary Clinton, a “museum-quality specimen of the Yankee – self righteous, ruthless, and self-aggrandizing,” managing to “destroy a good part of the liberty and morals of the American peoples.” Who, for example, was the abolitionist John Brown? A man born in Connecticut, who had financial backing and accomplices to assist him in his mass murderings of innocent Southerners on the premise that Southern slaveholders were evil sinners standing in the way of America’s “divine mission to establish Heaven on Earth.” From the pulpit, Henry Ward Beecher (brother to the woman (who never visited the South) but who nonetheless wrote “Uncle Tom’s Cabin” urged the young males to go to Kansas and kill Southern settlers. In fact, according to Clyde Wilson, “Henry did all he could to haste the onset of the conflict” – while living in luxury in Newport Connecticut and Europe.

Mr. Wilson asserts that most abolitionists knew little about black people, nor did they care to know. Abolitionism was a Yankee crusade to erase sin and erect a more perfect world regardless of the violation of to Americans’ constitutional rights such an undertaking forged. It is Yankee ideology that made an equation of God with America, thus fomenting the idiotic notion of a kind of existential infallibility between the U.S. government and the President such that both are incapable of doing wrong and thus are free to destroy anyone disagreeing with either.

Today, the United States is not a normal country; it is “cannon fodder for a ruling class so made by wealth and power that it seeks to dominate the Earth.” (“The Yankee Problem, Again”) No Southerners occupy seats in Congress or in governors’ office, and talk by the Blue states about secession (like California) is nothing but a temper tantrum by Yankees because they have not gotten everything exactly as they wanted it, says the author.

Of the last four pieces in this profound and stirring collection, the longest and most hard-hitting is “The Yankee Victorious: Why and How,” in which Mr. Wilson goes over the many causes and cases for the War of Southern Independence, while attacking the false and monocausally-defined myth that the War Between the States was fought purely over slavery.

He labels the assertion that slavery was the sole “cause” of The War as “superficial historianship” that approaches flagrant dishonesty. He reminds the reader that to prevent Southern secession,” the North, the U.S. government, and Lincoln, had alternative actions to select from, but finally chose war. No one helplessly “made” them decide. Strictly speaking and wisely, Mr. Wilson says what the war was “about” was the actual nature of the Union. This was a philosophical, even theological consternation about which everyone had concern and about which many today still have concern. In the first days of the U.S. government, the most fundamental American political division was between Jefferson and Hamilton.

“From the beginning Hamiltonians, largely affluent Northerners, had seen the federal government as a tool, the powers and activities of which were to be stretched and expanded at every opportunity.” And nationalism, the desirability of one territory unified under one strong government, had become a major concept in the Western world by the 19th century, providing major motivation for a war against the South. Even today the emotions of certain people who believe fervently in nationalism wrongly and laughably feel secession is actually treasonous.

Some of the other causes contributing to the conflict that ended in The War than those listed above and which the author outlines in this 27-page essay were the passage of the Proviso; the attempt of the North to dictate to the South the nature of its society; Lincoln’s backers who saw private profits in exploiting natural resources with government encouragement; Wall Street and the international banks, all of which enthusiastically supported Lincoln’s war; and the Kansas-Nebraska Acts, which restricted Southern settlements in new lands; and more.

Clearly, this book review is capable only of providing a gloss on the large variety of Mr. Wilson’s stirring, nuanced, and profound ideas, insights, facts, and tastes that this collection offers. Reading this tiny tome is a tour de force experience for many readers. Not only did I learn a lot, not only was what I learned fortifying and inspiring, but I as well found myself feeling deeply how important is the main premise of the book: There is a Yankee problem, and the Northern, nationalistic interpretations of America’s past must be re-analyzed coldly with the aim of destroying false conceptions and deliberate errors compounding that problem. If only this book might be in the pockets of every high school boy and girl studying American history so as to give them grounding as to how to maneuver through the thicket of certain dates and events from America’s misty past to not only better to understand America’s past accurately but themselves as well, as genuine if imperfect Americans.

One Comment