A Review of: On the Prejudices, Predilections, and Firm Beliefs of William Faulkner. By Cleanth Brooks. Baton Rouge, Louisiana: Louisiana State University Press, 1987. 162 pp.

When I think of the state of literary criticism in the academy today, I think of a New Yorker cartoon someone has put up in the liberal arts coffee lounge at Clemson. It shows a fool, in cap and bells, juggling before the king. The caption reads: “In France they consider him a creative genius.” Underneath someone has written: “Does this refer to Jerry Lewis or Derrida?” For the uninitiated, Jacques Derrida is the French critic who founded deconstruction, an arcane methodology that regards written texts as primarily self-referential wordplay. Whatever may be said for the metaphysics of this approach, it, along with structuralism and other recent forays into “critical theory,” is frequently more difficult to understand than the creative works it is meant to explicate. Glossolalia may or may not have its place in religion; in literary exegesis it is deadly.

How different things were when the Southern “new critics” were running the show. In the forties and fifties the most influential literary quarterlies in America preached and practiced a brand of aesthetic formalism that had been originated (in this country, anyway) by John Crowe Ransom and his followers at Vanderbilt University. Although careful to stress the integrity of literary artifacts against those who would see them as mere adjuncts of history or sociology, the “new critics” (as they were then known) never succumbed to the absolute relativism of the deconstructionists. If they sometimes approached poems as anagrams to be decoded, it was not with the casualness that one might approach the crossword puzzle in the morning paper. For them literature had an important, though not preeminent, role in a world of humane values. It was neither a religion, on the one hand, nor a bead game on the other.

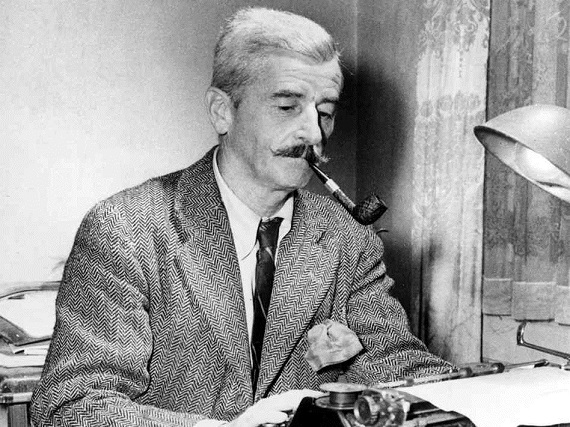

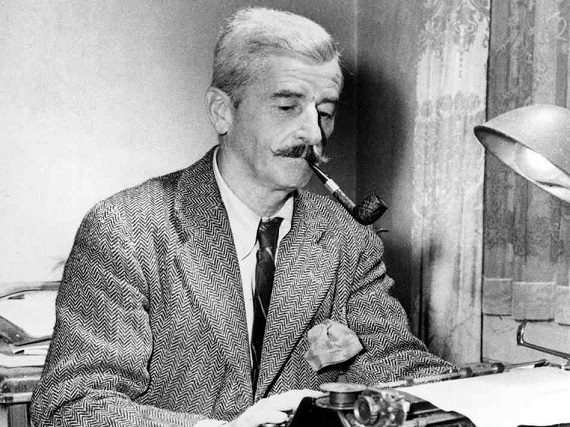

If John Crowe Ransom was the major theorist of the new criticism, its foremost practitioner was surely Cleanth Brooks. In a series of textbooks he co-edited with Robert Penn Warren and in his vastly influential collection of essays The Well Wrought Urn (1947), Brooks taught several generations of college students how to apply the principles of aesthetic formalism to actual works of literature. In fact, had he written nothing in the past forty years, Brooks would still be an important figure in the literary history of this century. Fortunately, he did not stop writing but has devoted himself since the early sixties to interpreting and popularizing the work of one of America’s greatest but most difficult novelists, his fellow Southerner William Faulkner. Only if we understand this missionary vocation can we appreciate Brooks’s most recent book on Faulkner as something more than what Douglas Bush considered all new criticism to be–an advanced course in remedial reading.

On the Prejudices, Predilections, and Firm Beliefs of William Faulkner is Brooks’s fourth and least scholarly book on Faulkner. For the most part it is a collection of lectures delivered since the early seventies. As oral presentations, these lectures must have impressed general audiences with their clarity and modesty, proving once again that Cleanth Brooks is a superb teacher and gracious human being. On the printed page, however, only a few of these pieces bear comparison with Brooks’s best work. His essay on “The British Reception of Faulkner” is one of these. It not only delivers the information promised in the title but also serves as a case study of the differences between professional American criticism and amateur British reviewing. (Although I prefer the latter to the former nine times out of ten, Brooks demonstrates that the British method is particularly ill suited to a writer as complex as Faulkner.) Of more obvious interest to the readers of this magazine are three unmistakably Southern essays–“Faulkner and the Fugitive-Agrarians,” “Faulkner and the Community,” and “Faulkner and the American Dream.”

In the first of these essays, Brooks answers Daniel Aaron’s charge that he and Robert Penn Warren have tried to distort the iconoclastic Faulkner into a kind of honorary Fugitive and Agrarian. Through a solid marshalling of evidence, Brooks shows that the Nashville crowd was more critical of Southern life than is generally supposed and that Faulkner was not nearly as hostile to his home region as simple-minded civic boosters accused him of being. Both Faulkner and the Fugitive-Agrarians lived in and worked out of that sense of historical discontinuity known as literary modernism. Although not identical, their responses to this situation have more in common with each other than either does with the Victorian certitudes of the New South. The Nashvillians were among Faulkner’s earliest admirers. And in his only recorded comment on the Vanderbilt writers, Faulkner has his character Charles Mallison observe that “Huey Long in Louisiana had made himself founder owner and supporter of what his uncle Gavin said was one of the best literary magazines anywhere, without ever once looking inside it.” The magazine in question was the Southern Review, edited by Robert Penn Warren and Cleanth Brooks.

In his discussions of “Faulkner and the Community,” Brooks identifies the quality that most distinguishes the world of Yoknapatawpha (and the South in general) from what we find in the fiction of Faulkner’s most gifted contemporaries. The characters of Hemingway and Fitzgerald may exist in a crowd (a random group of onlookers) or even a society (persons drawn together for mutual profit). What we do not find in their work, or in much modern American fiction set outside the South, is a fully functioning community-“a group of people united by common likes and dislikes, aversions and enthusiasms, tastes, ways of life, and moral beliefs.” Neither Faulkner nor Brooks is foolish enough to think that a community is invariably a force for good. But it is an invaluable literary resource, giving fictional characters a context within which to play out their individual dramas. Remove the community of Jefferson from “A Rose for Emily” and you have only the sort of tabloid melodrama found in the supermarket check-out lines—SPINSTER SLEEPS FOR FORTY YEARS WITH BOYFRIEND’S CORPSE.

Paradoxically, one of the fruits of true community is the right to privacy. (Respect for Miss Emily’s privacy allowed her literally to get away with murder.) The dignity and autonomy of the individual are more likely to be respected where people are united by shared values than in a totally atomistic society. In a community manners and customs regulate behavior. In a mere society, man’s actions are constrained only by brute force (either public or private) or by the fear of force. For Faulkner the American Dream lay in the promise of true community. When the national media began invading his privacy, he was prompted to begin a series of essays (still incomplete at the time of his death) on the demise of that promise in present-day America. In a thought-provoking lecture delivered at the International Faulkner Conference in Japan, Brooks compares Faulkner’s critique of contemporary American society with that of Christopher Lasch, whose Culture of Narcissism was published sixteen years after Faulkner’s death. Like Lasch and others capable of seeing beyond their image in the pool, Faulkner knew that a man who has lost all voluntary codes of behavior is apt to be destroyed by either the Leviathan or the jungle.

Faulkner has now been gone for a quarter century and has long since passed into the literary pantheon. Cleanth Brooks, however, is still very much with us. Only nine years younger than Faulkner, he is one of the last major Southern critics of what might be regarded as Faulkner’s generation. (Andrew Lytle and Robert Penn Warren are the others.) Of that generation, Andrew Lytle observed, it “was the last moment of equilibrium . . . the last time a man could know who he was. Or where he was from. It was the last time a man, without having to think, could say what was right and what was wrong.” Without that equilibrium one cannot know the world well enough to recreate it in art or evaluate it in criticism. Perhaps for that reason we are constantly hearing reports of the death of the novel and of the death of criticism. But as long as Faulkner and Brooks continue to be read those reports will remain greatly exaggerated.