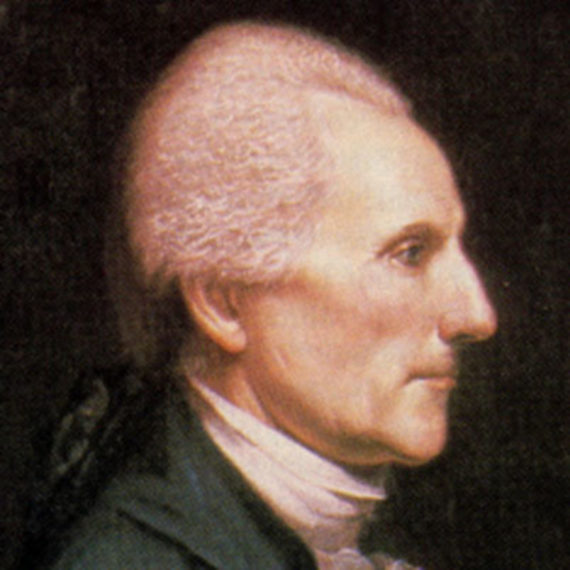

Richard Henry Lee was a patriot, Anti-Federalist, and statesman from his “country,” Virginia. He led the charge for independence in 1776 and was a powerful figure in Virginia political life. He served one term as president of the Continental Congress and was elected a United States Senator from Virginia immediately after the ratification of the Constitution. His role in the founding period is often overlooked due to his “personality” and the slapstick characterization of him in the musical 1776. Lee was a Southern aristocrat, sometimes considered pompous and arrogant, but he was not a bumbling idiot. John Adams, in fact, called him a “masterly man,” though “tall and spare.” Excluding Lee from a list of Founding Fathers would be a travesty, for he was as important to the cause of independence as Jefferson, Adams, and Franklin.

Lee was descended from one of the oldest and most powerful families in Virginia. His great-grandfather, Richard Lee, was the first of the family to settle in Virginia and at one time served as the Attorney General and Secretary of State for the colony and was a member of the king’s council. His father, Thomas Lee, served in the Virginia House of Burgesses and as acting governor of Virginia. His mother, Hannah Harrison Ludwell, was a member of the powerful Harrison family of Virginia.

Richard Henry Lee was born in 1732 at the family plantation, Stratford. His brother, Francis Lightfoot Lee, and nephew, Henry Lee III (“Light Horse Harry”), would become American military heroes, but Richard Henry Lee was more like his grandfather, Richard Lee II, often called “Richard the Scholar.” His service would be rendered in the political break with Great Britain and as a champion of the rights of Englishmen.

Lee was educated by private tutors and was graduated from the Wakefield academy in Yorkshire, England, in 1751. He received a solid background in the classics, government, and history, and in 1752, Lee returned to Virginia and practiced law. He began his public career in the Virginia House of Burgesses in 1757 and became a justice of the peace for Westmoreland County in 1758. He was a leader in the House of Burgesses, an ally of Patrick Henry, and an early opponent of Parliament’s authority to tax the colonies. He wrote in 1764, one year before the infamous Stamp Act, that taxes imposed on the colonies without proper representation in Parliament were akin to an “iron hand of power” and a violation of the British constitution. “Surely no reasonable being would,” he stated, “quit liberty for slavery; nor could it be just for the benefited to repay their benefactors with chains instead of the most grateful acknowledgments.”

He was not in attendance in 1765 when Henry presented his famous Stamp Act Resolves to the House of Burgesses, but he agreed with him. Lee, along with several other Virginia gentlemen, attempted to force the Stamp Act collector to resign his appointment, and Lee later called the collector “an execrable monster, who with parricidal heart and hands,” would “ruin…his native country.” Lee organized the first non-importation association in the colonies, the basic structure of which later became the Virginia Association and Continental Association for the boycott of British goods. In contrast to the violent opposition to Parliamentary acts in New England, Lee chose boycotts and “persuasion” and never threatened tar and feathers or the destruction of property. His was a gentlemanly rather than a radical approach and based upon the constitutional rights of Englishmen, which his family had fought to preserve for generations.

The Townshend Acts of 1767 were, to Lee, an even graver injustice. He called them “arbitrary, unjust, and destructive of the mutual beneficial connection which every good subject would wish to see preserved.” Lee began urging for colonial committees of correspondence, not unlike those which Samuel Adams suggested a few years later. He was present when the House of Burgesses was dissolved in 1769 and participated in the famous Raleigh Tavern meeting where the Virginia Association, which organized the non-importation of British goods, was agreed upon. As British violations of colonial sovereignty became more pronounced, Lee was more aggressive. He pushed his call for committees of correspondence in 1773, stating that such action should have been taken from the beginning of the conflict as a means to achieve “perfect understanding of each other, on which the political salvation of American so eminently depends.” And in 1774, Lee, Henry, and Thomas Jefferson called for a day of fasting and prayer in protest of the closing of Boston Harbor. He called this action of Parliament the “most violent and dangerous attempt to destroy the constitutional liberty and rights of all British America.”

Lee was elected as a member to the First Continental Congress in 1774 and he enthusiastically supported the adoption of the Continental Association for boycotting British goods. By 1775, he was urging independence. The Fifth Virginia Convention followed his lead and declared Virginia independent from Great Britain in May 1776. They sent Lee instructions to present a series of resolves to the Second Continental Congress calling for the independence of all the colonies in order to form foreign alliances and establish a confederation for common defense. He presented the “Lee Resolutions” to Congress in June 1776. The language was clear: “Resolved, That these United Colonies are, and of right ought to be, free and independent States, that they are absolved from all allegiance to the British Crown, and that all political connection between them and the State of Great Britain is, and ought to be, totally dissolved.”

Lee left the Congress one week later to participate in the formation of the new Virginia government, at that time a much more prestigious role than hammering out a formal declaration of independence. He had already laid the rhetorical groundwork for independence and Jefferson copied much of Lee’s language and that of George Mason’s Virginia Declaration of Rights when he wrote the Declaration of Independence.

Lee later returned to Philadelphia and along with his brother Francis Lightfoot Lee, became one of two Lees to affix his signature to the Declaration. Lee was an active participant in the Continental Congress, but was worn out by his duties and resigned his seat before the end of the war. He was re-elected to the Congress in 1784 and served as the president of that body from 1784 to 1785.

As the clamor for a stronger central government grew more pronounced, Lee attempted to quiet discontent over the Articles of Confederation. Virginia was his native country and though he could see that the powers of government under the Articles were often insufficient, he cautioned men to avoid granting “to Rulers an atom of power that is not most clearly and indispensably necessary for the safety and well being of Society.” He opined that the central government should not have the power of “both purse and sword.” Lee was offered a seat at the Philadelphia Convention of 1787 but declined because he believed it would be unconstitutional and improper to serve in both the Congress under the Articles of Confederation and a convention charged with altering the existing government. But when the Constitutional Convention concluded its work in September, Lee quickly became an outspoken opponent of the new government.

He wrote to George Mason in October 1787 that the Constitution would produce “a coalition of monarchy men, military men, aristocrats and drones whose noise, impudence and zeal exceeds all belief.” Lee believed that the “commercial plunder of the South” and the possibility of “tyranny” or “civil war” would be the only results from the adoption of the Constitution as it stood, and recommended withholding “assent” until amendments protecting civil liberty were added. Later in a letter to Samuel Adams he said, “the good people of the U. States in their late generous contest, contended for free government, in the fullest, clearest, and strongest sense. That they had no idea of being brought under despotic rule under the notion of ‘Strong government,’ or in form of elective despotism: Chains being still chains whether made of gold or iron.” Clearly, Lee believed the Constitution would turn the liberty-loving people of all states into slaves, bound by a government of elected tyrants whose sole purpose would be to glorify and enrich themselves. Lee understood free government to be limited government.

During the months leading to Virginia’s ratification convention in 1788, Lee penned seventeen letters entitled Letters from the Federal Farmer to the Republican that appeared in two pamphlets. They outlined his arguments against the Constitution and equaled the Federalist in depth. Taken as a whole, they are the best expression of Anti-Federalism outside of the ratification conventions. Lee expressed fear that the Constitution supplanted a federal with a consolidated government. “Instead of being thirteen republics, under a federal head, it is clearly designed to make us one consolidated government.” He reasoned that such a system would render the people in the “remote states” vulnerable to “fear and force,” and it would end in “despotic government.” Lee conceded that parts of the government under the Constitution were sound, but without a bill of rights and strict limitations on government, the people would be subjected to the worst evils of power.

The Letters emphasize that the Constitution is a compact among the states. If the states approve the Constitution they were entering into an agreement, a compact, and Lee insisted that if the state governments ceased to exist, the federal government “cannot remain a moment” because it was the creation of the states; moreover, the federal government could not have any powers that were not expressly delegated to it by the people of the states.

Lee was elected as a delegate to the Virginia ratification convention in 1788, but he did not attend due to poor health. Still, he privately pressured other delegates to consider amendments prior to ratification. Lee considered freedom of the press, frequent elections, and trial by jury vital for “good” government for “the violation of these…will always be extremely convenient for bad government.” He also believed state sovereignty offered a protection against “arbitrary rule.” If, however, the proposed amendments were not adopted by the new government within two years, Lee recommended that Virginia be “disengaged” from the ratification. Another word for “disengaged” is secession. When the Constitution was ratified by Virginia, Lee wrote, “’Tis really astonishing that the same people, who have just emerged from a long and cruel war in defense of liberty, should now agree to fix an elective despotism on themselves and their posterity!”

Through Henry’s power in the Virginia legislature, Lee was elected to serve as a Senator from Virginia in 1789. His main focus during the early days of the Senate became the consideration and adoption of a bill of rights. He worked zealously to ensure that the bill of rights would be crafted according to the designs of the Virginia convention and criticized James Madison for his abridgement of the original list. Lee called the final list “mutilated and enfeebled,” and concluded, “What with design in some, and fear of Anarchy in others, it is very clear, I think, that a government very different from a free one will take place ere many years are passed.” He was sick for much of his time in the Senate and resigned his seat in 1792. Lee returned to his plantation, Chantilly, and died two years later at the age of 62.

Like his compatriots from his native state, Lee was first and foremost a Virginian and a Southerner. He once wrote to Samuel Adams that, “So extensive a territory as that of the U. States, including such a variety of climates, productions, interests; and so great differences of manners, habits, and customs; cannot be governed in freedom, unless formed into States sovereign sub modo, and confederated for common good.” While in the Senate, he informed Patrick Henry that “The most essential danger from the present system arises, in my opinion, from its tendency to a consolidated government, instead of a union of Confederated States.” He urged Henry to fill state offices with men who would firmly oppose encroachments on state power, for states were the only reliable safeguards against tyranny and the preservation of traditional order.

Lee believed the states should never be consolidated into an “American people” because they were, in reality, the people of the several states with different cultures and interests. He had led Virginia to independence in 1776 and from that point on he considered Virginia to be an independent, sovereign republic, his country. When his nephew Robert E. Lee supported the secession of his state in 1861, he was simply following a family tradition.

A slightly different version of this essay was first published in Brion McClanahan’s Politically Incorrect Guide to the Founding Fathers (Regnery, 2009).