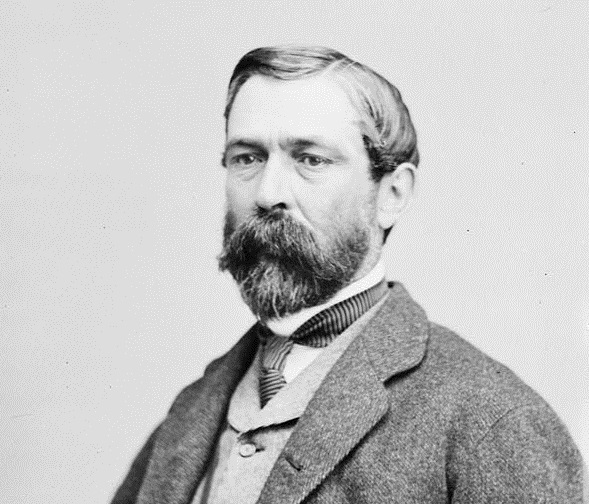

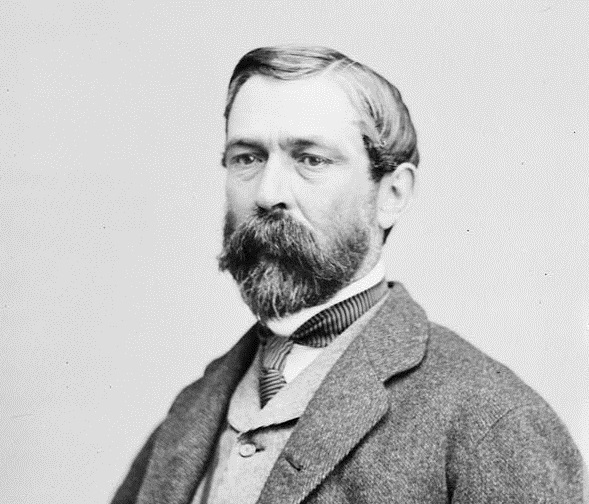

General Richard Taylor was only son of President Zachary Taylor. His father and mother were natives of Virginia, and his grand father, also a Virginian, commanded a brigade of Virginia troops in the battle of Brandywine. The hereditary residence of the family was in Orange county, Virginia.

President Taylor’s eldest daughter married Lieutenant Jefferson Davis, the late President of the Southern Confederacy; another daughter married Surgeon Wood, of the United States army, and the other was Mrs. Bliss, now Mrs. Dandridge, of Winchester. When her father was President of the United States, it was Mrs. Bliss who gracefully extended the hospitalities of the President’s house. Quite early in life General Dick Taylor took charge of his father’s plantation in Mississippi, and soon afterwards moved to a fine estate in Louisiana, to the development of which he addressed himself until the war of 1861 called him to the field. He married Miss Bringer, of Louisiana, thereby connecting himself with several able and prominent men of the State and with one of the most respectable of the Creole families.

His active, vigorous mind could not find scope in the avocations of a wealthy planter, and he asserted himself in every important State or national movement which interested his people from the time he assumed the responsibilities of a citizen to the day of his death. The prominent part he took in the Charleston Convention and other important events preceding the election of Mr. Lincoln, are fully set down in his book, which is almost a posthumous record of his own remarkable career, and made it inevitable that he would assume a prominence in the struggle he had endeavored to avert.

His military career was exceptionally successful. He was never involved in disaster or identified with any defeat during the four years of his varied and active service. As commander of a brigade under Jackson in the Valley, he was conspicuous by his frequent and critical success, and from the day he arrived in the Trans-Mississippi Department till the day of his promotion to command of the Department of Mississippi and Alabama, his history was a brilliant record of incessant activity and unfailing success, culminating in the remarkable victories of Mansfield and Pleasant Hill, which are distinguished above all others by the fact that they afford the most conspicuous instance in which a Confederate commander having won a victory followed it up. Taylor having beaten Banks one day at Mansfield, pursued him twenty-three miles next day, encountered his reinforced army at Pleasant Hill, and beat it again. His operations alone in that Department gave the gleams of hope which redeemed the four years of defeats, inactivity and despondency of the Confederate armies of the Trans-Mississippi Department. When he recrossed to this side of the river, nothing was left to him to do but to provide for the decent obsequies of the corpse of the Confederacy, and in executing this sad duty he evinced the highest capacities of his character.

His promptness and boldness in recognizing the responsibilities of his position, and his tact in the conduct of his negotiations with General Canby, secured to his command the best possible terms of surrender and lent to the closing scenes of his capitulation a dignity and good order which won him the lasting respect of all who were concerned in it. On the close of the war he returned to his ruined estate, which was soon after confiscated and sold. The Legislature of Louisiana granted him a lease of the new canal, which was so administered as to afford him a becoming livelihood, and it is hoped that he had provided sufficient means for the support of his three orphaned daughters.

His book, which has attracted such wide-spread admiration, is but the transcript of the brilliant wit and vivid pictures presented. by his ordinary conversation, which, had it been directed to the topics of the work, might have been stenographed just as is there written.

It seems probable that had he lived he would have been placed where his wonderful acquirements and endowments might have greatly served his people.

His absolute self-reliance amounted to a total irreverence for any man’s opinion, and he was so intractable as never to be regarded as a safe subject to the behests of a political party; but he has, by the very last act of his life, made an enduring record which holds him among the most remarkable men of the times in which. he lived.

He was marked in the expression of his friendships and of his. antipathies — these regard the conduct of men rather than the men themselves; and an intimate personal acquaintance, which has been enjoyed ever since he reached manhood, enables me to bear testimony to many kindly acts of this gifted man.

His scholastic experience was confined to America. He was never at school in Edinburg, as has been stated. But no college course could measure or restrain or develop his genius — mankind was his study and the world his curriculum.

He was only fifty-three years old when he died — young enough for a great career. He died in the enjoyment of the first flush of the great success of his first and only book.

This essay was originally published in the Southern Historical Society Papers, Vol. VII.