From April to July of 1863 British Lieutenant Colonel Arthur J. L. Fremantle visited all but two Confederate states. He entered at Brownsville, Texas and finished by observing the battle of Gettysburg from the Rebel side where he was a character in both Michael Shaara’s novel, The Killer Angels, and the corresponding film, Gettysburg. About 140 years later one of his descendants, Tom Fremantle, retraced his ancestor’s steps in the company of a pack mule. Tom summarized the second trip in his book The Moonshine Mule. By the time Tom reached northern Virginia he noticed certain people were:

…dismissive of the South. [Some were on a lark while others] were…stuffy types whose opinions had nothing to do with political morality and everything to do with smugness. “My dear, you walked through Alabama – I wouldn’t even drive through there! The South’s an embarrassment, it’s worse than the Third World.” When I asked these people if they had ever been to Mississippi or South Carolina, they usually replied, “Lord, no! Never!”…To my surprise I often became passionate in my defense of the South.

Although presently most Northerners accept fellow countrymen from other regions in good will, Tom probably did not realize the contempt toward Southerners displayed by the smug minority stretches back at least 150 years. For example, in 1861 a Massachusetts mill owner, abolitionist, and antebellum weapons supplier to John Brown named Edward Atkinson wrote a booklet entitled Cheap Cotton by Free Labor. His concept of “free” meant labor performed by non-slave workers. He advocated destruction of the “planters and businessmen of the cities” in order to rebuild the Union with the “poor white trash composing the large majority of the Cotton States.” Throughout the War Atkinson persistently lobbied for the invasion, occupation, and redistribution of Southern lands for the deliberate purpose of cultivating cotton with free labor.

While its unsurprising that an abolitionist dismissed Southerners as “poor white trash” Atkinson’s sympathy for ex-slaves was inconsistent with his putative ideology.

[For purposes of argument] we may admit that we must have cotton, and that the emancipated slave will be idle and worthless; we may [disregard that] in our southern climate, labor or starvation would be his only choice…let him starve and exterminate himself if he will and so remove the Negro question – still we must have cotton.

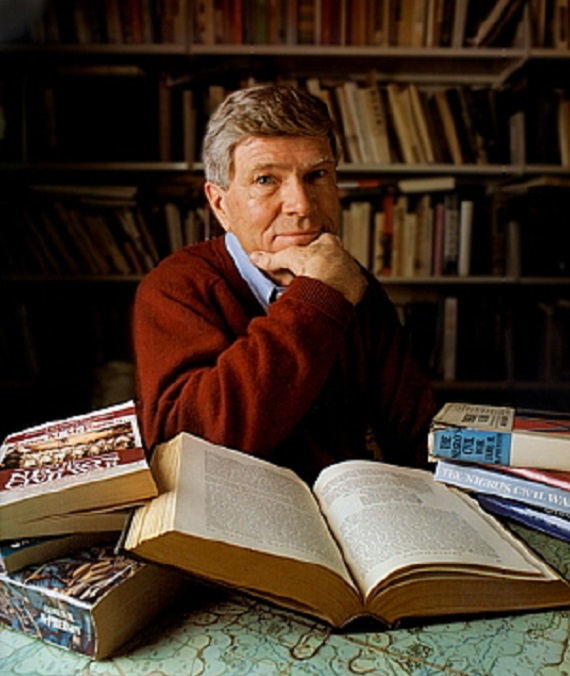

Since the cause declarations of some of the seven Cotton States in the first secession wave cite the protection of slavery as a prime reason for leaving the Union, Righteous Cause historians conclude slavery was the only cause of the Civil War. The paragon example is Battle Cry of Freedom author James McPherson who said, “Probably…95 percent of serious historians of the Civil War would agree on…what the war was about . . . which was the increasing polarization of the country between the free states and the slave states over issues of slavery….” McPherson and his acolytes dismiss all other issues even when such factors are evident by comparing the US and Confederate constitutions. For example, the Southern central government was prohibited from (1) imposing protective tariffs, (2) spending taxpayer money on public works, and (3) subsidizing private industries. Although Virginia, North Carolina, Tennessee, and Arkansas joined the Confederacy and doubled its White population only after the Federal government required they provide soldiers to invade the Cotton States, Righteous Cause historians insist that the four upper-south states also fought only for slavery.

The Righteous Cause also dismisses the fact that two-thirds of Southern families did not own slaves. Acolytes spill oceans of ink arguing that non-slaveholding Southerners willingly left their homes and risked their lives chiefly – if not exclusively – to promote the “slavocracy.” Although tens-of-thousands of Union volunteers rose up spontaneously to defend their homes in Ohio, Indiana, and Pennsylvania when Rebel armies approached those states, Righteous Cause historians don’t credit Southerners with the same instinct, evidently because of endemic Yankee moral superiority. Of course it’s illogical and a lie. As the venerable William C. Davis writes:

The widespread northern myth that the Confederates went to the battlefield to perpetuate slavery is just that, a myth. Their letters and diaries, in the tens-of-thousands, reveal again and again, that they fought and died because their Southern homeland was invaded and their natural instinct was to protect their home and hearth.

Righteous Cause Mythology falsely equates the reasons for secession with the reasons Southerners chose to fight. But they are not the same. Southerners fought to defend their homes. The more pertinent question is to ask why Northerners fought. After all, the Northern states could have let the Southern states leave in peace, without any War at all. It was precisely what prominent abolitionists frequently advocated prior to the War. Examples include William Lloyd Garrison, Henry Beecher, Samuel Howe, John Greenleaf Whittier, James Clark, Gerrit Smith, Joshua Giddings, and even Massachusetts Senator Charles Sumner who would become a leading war hawk. For years Garrison described the constitutional Union as “a covenant with death and agreement with hell.”

The Righteous Cause Myth is a natural consequence of the false insistence that the South fought for nothing but slavery. Thus, if the South waged war only to preserve slavery, then it logically follows the Yankees waged war for the sole purpose of freeing the slaves. It is a morally comfortable viewpoint for historians who came of age during and after the twentieth century civil rights movement. But it’s as phony and useless as a football bat.

Lincoln never told Confederate leaders he would end the War if the Rebels merely freed their slaves. He always insisted upon reunification. During the second half of the war his peace terms were reunification and emancipation, but during the first half both the Federal President and Congress required only reunion. Furthermore, in his first inaugural Lincoln noted that Congress passed and sent to the states for ratification an amendment that would forever protect slavery in the states where it was legal, adding he had “no objection to it being made express and irrevocable.” Earlier in the same address he said, “I have no purpose, directly or indirectly, to interfere with the institution of slavery in the States where it exists. I believe I have no lawful right to [or] inclination to do so.” Finally, about a month before his preliminary Emancipation Proclamation in September 1862 Lincoln wrote a newspaperman, “If I could save the Union without freeing any slave I would do it, and if I could save it by freeing all the slaves I would do it; and if I could save it by freeing some and leaving others alone I would also do that.”

Northern attitudes toward Blacks were also inconsistent with Righteous Cause Mythology. Sixteen of the twenty-two loyal states did not permit them to vote although their population percentages were tiny. The Oregon constitution prohibited free Blacks to immigrate, Illinois would not admit them unless they arrived with $1,000 or more, and other Northern states had similar restrictions. Around the mid point of the war Lincoln sent Adjutant General Lorenzo Thomas into occupied regions of the lower Mississippi Valley to recruit African-Americans as soldiers and make arrangements for their families. Thomas tried to send Blacks to free states north of the Ohio River, but they were forcibly returned and he concluded:

It will not do to send [Black refugees]…into the free states, for the prejudices of the people of those states are against such a measure and some…have enacted laws against the reception of free negroes…[Ex-slaves] are coming in upon us in such numbers that some provision must be made for them. You cannot send them North. You all know the prejudices of the Northern people against receiving large numbers of the colored race. Look upon the river and see the multitude of deserted plantations upon its banks. These are the places for those freedmen..

General Thomas leased plantations to civilian operators including many Northerners as well as some ex-slaves and White Southerners remaining on their lands. A War Department survey indicated that the apparent promise of quick cotton riches attracted undesirable, inexperienced, and underproductive Northern freebooters. Specifically it concluded that the “old planters [were] dealing fairly with the freedmen…[and] have paid them more promptly, more justly and apparently with more willingness than new lessees…” The Southern planters who remained took a longer-term view. They were primarily concerned with earning a living and holding onto their property until the return of peace and civil government.

The Righteous Cause Myth crumbles under the weight of such inconsistencies, but it’s coup de grace comes upon realization that the North fought for the same reason that wars of conquest are always fought, to wit, economic supremacy. Prior to the War the South generated over 75% of the nation’s exports thereby providing the economic engine to sustain a favorable trade balance for the nation as a whole and to support the maritime and other commercial trades of the North. Moreover, the lasting Republican policies after the War treated the South as an exploited internal colony while promoting prosperity across the North. Tariffs remained over 40% for the next fifty years thereby requiring Southerners to purchase artificially overpriced manufactured goods from the North while exporting their own produce to world markets that were competitive to the Nth degree. Republicans used the South’s African-American voting block to retain power for about a dozen years, but thereafter abandoned the Freedman once Republican voting strength in other parts of the country no longer compelled the Party to support Blacks.

Although both Black and White Southerners were impoverished after the War, there was almost no Federal relief. Instead the Republicans imposed a tax on cotton but refused to likewise tax the farm goods specific to Northern states. While the Republican Congress funded a Freedman’s Bureau to look after the interests of ex-slaves, the cotton tax alone generated nearly three times as much revenue as was spent by the Freedman’s Bureau during its entire existence. Thus, Yankee taxpayers didn’t pay for it. Despite its greater need, Federal public works spending in the South was tiny compared to other parts of the country. From 1865 – 1873 less than ten-percent of Federal public works investment was in the South. Massachusetts and New York alone got more than all the states of the former Confederacy combined. During that period the cotton tax alone was about seven times greater than Federal public spending in the South. In short, the South was given no “Marshall Plan” for recovery as was done for Europe after World War II.

For at least twenty years after the War Southern taxpayers witnessed over half of their Federal payments used to fund items that would have been considered reparations if the Confederacy had been an independent defeated country. During that time more than half of the Federal budget was for three items: (1) interest on the Civil War debt, (2) Union veteran pensions, and (3) surpluses for retiring the Federal debt principal. If Germany and Japan were required to pay (1) GI pensions and benefits, (2) interest on US War Bonds, and (3) monies for retiring US War Bonds after World War II such payments would be reparations.

Righteous Cause Mythology ignores such points. Furthermore, it recently became so distorted that it passed through the looking glass where statements from original sources consistent with the mythology are taken at face value, but those inconsistent with it are considered to be lies. In such an upside-down world historical characters like Lincoln did not mean what they wrote or said when it fails to conform to the mythology. Earlier this year Righteous Cause Mythologist Stephen Berry of the University of Georgia put it this way:

But proving that the South seceded to defend slavery is not the same as proving that the North went to war to destroy it. This case has been made…only in the last ten years…James Oakes has shown that virtually every Northerner, including Lincoln, who pledged “not to interfere with slavery where it already existed” was essentially lying.

Well, in August 1864 Lincoln wrote that he was concerned enough voters might support George McClellan in such a pledge that the general might win the next Presidential election. But, perhaps Abe was just lying. Such assumptions are permitted in Righteous Cause scholarship. And like Tom Sawyer said when the Pastor asked him what the Bible says about lying, Righteous Cause Mythologist can respond, “It’s an abomination unto the Lord and an ever present help in a time of trouble.”

2 Comments