In June 2017, The Atlantic published a hit-piece on Robert E. Lee titled “The Myth of the Kindly General Lee.” The article made the rounds on Leftist echo chamber social media accounts and quickly found favor with the popular Leftist Twitter historians, a collection of “distinguished professors,” some without a substantial publication record, who like to trumpet their status as “actual historians” when “amateurs” propose a “lost cause” version of Southern history and the “Civil War.” It has since been paraded by these “actual historians” as the conclusive popular article on “the fiction of a person who never existed.”

The irony of course is that this piece was written by an amateur, Adam Serwer, who has the same credentials as David Barton, Dinesh D’Souza, Brian Kilmeade, Bill O’Reilly, or Ta-Nehisi Coates, meaning none. That doesn’t matter. What matters to the Twitter historian brigade is that Serwer has the “correct” position on Lee. By the way, so do the “conservatives” Barton, D’Souza, Kilmeade, and O’Reilly.

A recent dust-up between Mississippi Senatorial candidate Chris McDaniel and the Twitter historian brigade nicely illustrates the group-think mentality of the “actual historians” in the Twitter brigade. McDaniel stated it was the “truth” that Lee:

was the most decorated soldier in the U.S. Army. He was a man of unimpeachable integrity. Lincoln offered him command of the Union Army, but Lee refused only because his loyalty was to Virginia. Lee opposed both secession and slavery. And yet to the historically illiterate left, a man who opposed both slavery and secession has come to symbolize both slavery and secession.

McDaniel made a mistake in calling Lee “the most decorated soldier in the U.S. Army.” That would have been Winfield Scott, the only man other than George Washington to achieve the rank of Lieutenant General in the antebellum period. Scott, however, did call Lee the finest soldier he ever knew, and Lee earned his reputation as “the indefatigable Lee” in the 1840s during the Mexican War, long before the bloody conclave of the 1860s. In other words, Lee was not the most “decorated solider,” but he was certainly one of the most respected.

But the rest of his statement contains elements of truth. Regardless, the Twitter brigade pounced on the “amateur” McDaniel in nothing short of an apoplectic rage.

These gate keepers of acceptable thought dissected McDaniel’s statement line by line and offered what are now predictable cliches and platitudes: Lee was a white-supremacist and a traitor who explicitly supported slavery by leading the Army of Northern Virginia against the Union.

These “actual historians” knowingly or unknowingly often regurgitate Serwer’s Atlantic diatribe while advancing a narrative that is saturated with ahistorical and often hypocritical presentism.

Take for example Lee’s positions on slavery. Lee could certainly never be confused for an abolitionist. Like most Americans–not just Southerners–of his day, he believed the abolitionists to be dangerous reformers bent on destroying the peace and security of the United States. Abolitionists were run out of town in many Northern States, and the rigid proslavery ideology that most people associate with the South was born in eighteenth-century Massachusetts and Connecticut.

But does that make Lee “proslavery?” There is no evidence that he shared the same positions as Thomas Dew, William Harper, or James Henry Hammond. Lee held the dominant view of race relations in America in the antebellum period. His 1856 letter both condemning slavery as a “moral and political evil” while concurrently insisting that African-Americans were racially inferior and at that point not suited to freedom would not have been shocking or debatable to almost anyone at the time, North or South. Just two years later, Abraham Lincoln made similar statements in the now famous Lincoln-Douglas debates. Virtually all of the founding generation held similar views, as did Leftist heroes like John Muir of Sierra Club fame. Even Harriet Beecher Stowe made racist statements in both the antebellum and postbellum periods.

Why is Lee held to a different standard? Simple. Virtue signaling on the part of the Twitter brigade creates followers and advances careers. You won’t become an Ivy League professor by praising Lee or by innocently offering a balanced appraisal of the man. The mob requires obedience to acceptable thought. It is they, not the “Lost Causers,” who have become boxed into a “myth.”

Lee, of course, became a de facto slave owner when his father-in-law, George Washington Parke Custis, died in 1857. Both Serwer and the Twitter brigade consider this period to be the definitive example of Lee’s position on race and slavery, and both rely on a misreading and distorted interpretation of Elizabeth Brown Pryor’s description of Lee in her Lincoln Prize winning book Reading the Man as evidence of Lee’s cruelty.

Lee did require Custis’s former slaves to work once he became executor of the will, something they had not done in years. He also hired them out to other plantations in an attempt to make Arlington solvent. Custis left the estate in terrible shape, both physically and financially. Serwer and the Twitter brigade cite this as partial evidence of Lee’s inhumanity, as an attempt to “break up families.” One Twitter brigade historian actually suggested Lee broke up families by selling them off. That never happened. Lee did separate family members in the hiring out process, but he never sold a single slave. Lee was in a difficult situation. In order to keep Arlington and not sell it off, he had to get out of debt. In order to get out of debt, he had to make the estate profitable and doing so required that the Custis slaves be forced to work, either at Arlington or on neighboring plantations, something they did not want to do and openly resisted. This was understandable based on Arlington tradition and Custis’s longstanding promises of freedom and his labor practices. But manumission had been made illegal in Virginia, and so to criticize Lee for not immediately freeing Custis’s former slaves lacks historical understanding and context. Even Pryor states that “Virginia law made this [immediate emancipation] difficult, but the law had been circumvented before at Arlington.” In other words, Lee possibly could have broken the law, but it was not easy to do. All of the hand-wringing, then, concerning Lee’s handling of the estate is based on pure speculation on what he could have done differently–and frankly what the courts may have allowed–based on modern conceptions of justice. It’s also understandable for Lee to want to save Arlington, his wife’s birthright, but the Twitter brigade only seeks to understand one side and condemn the other. That is opinion, not history.

A Virginia court finally forced Lee to sell off portions of Arlington in 1862 in order to meet the final requirements of the Custis estate and to free the slaves. The Southern legal system was complex. Even Pryor describes Lee’s actions at this point in fairly sympathetic terms. “Determined to uphold his trust, Lee used his own funds and the sale of land to accomplish all of G.W.P. Custis’s exacting requirements. He also tried to help some of the freed men hire their labor, and resisted attempts by the white community in the Pamunkey region to keep them in bondage.”

Both Serwer and the Twitter brigade also claim it to be a fact that Lee had at least three slaves whipped and their wounds washed with brine to inflict pain. Sewer goes so far as to believe that Lee was at the whipping and ordered a more brutal job. This is at minimum debatable and probably a lie. In 1866, a former slave named Wesley Norris gave an interview to the National Anti-Slavery Standard where he described the whipping in question. Norris, a cousin, and his sister ran away from Arlington in 1859 and were subsequently recaptured after Lee offered a substantial bounty. According to Norris, Lee ordered them whipped and tortured before hiring them out further South. The story was initially picked up by the abolitionist press in 1859 and then again after Norris gave his interview in 1866. The first articles appeared in the New York Journal in June 1859, just a few months before John Brown’s raid on Harper’s Ferry. Lee publicly refused to answer the charge against him and did not directly comment on it privately, telling his son that the whole business “has left me an unpleasant legacy.” If Lee was so vindictive, why would it be “an unpleasant legacy?” Pryor did not include this last statement in the discussion of the event, but even she suggests that these Journal articles were “exaggerated.”

She certainly believes Norris, however, and asserts that every part of his story can be verified. Not quite. Norris gave the interview to, in Pryor’s words, “dispel the notion that Lee was a kind and humane slave owner.” She thinks Norris had nothing to gain by the interview. This may be true, but the newspaper that published the story in 1866 absolutely did. Historians–not just “lost cause neo-confederates”–have long questioned the validity of abolitionist accounts of slavery, particularly when “slave interviews” were filtered through abolitionists who could take liberty with the information. They were often purposely sensationalized and written for a sympathetic audience and were by no means non-partisan. The Norris account was published on the one year anniversary of Lincoln’s assassination, certainly as an attempt to draw attention to Lee’s character and to validate the “righteous cause myth” of the War. Pryor even contradicts herself by admitting that the whipping itself cannot be validated and that Norris carried no scars from such a violent event. And Lee twice denied it happened later in life. Whom are we to believe? Why would Lee lie in a private letter to his son in 1859 when he had nothing to lose? In either case, it is not a definite “fact” as either Serwer or the Twitter brigade claim that Lee either 1) had the slaves viciously whipped and tortured or 2) that he was there for the event, if it happened at all. To claim either as a fact is to distort the record for purely partisan reasons, something the Twitter brigade consistently chirps against when Lee is described as a “Christian gentleman” but is more than willing to do if it supports their position.

Was Lee a traitor? Next to Lee being a “white supremacist,” this is the most common charge leveled against him. Lee opposed nullification and secession his entire career. His father was a firm Federalist, and Lee never showed any hint of dissent from this position during his life. His oath in 1825 after leaving West Point required him to “solemnly swear or affirm (as the case may be) that I will support the constitution of the United States…” and “to bear true allegiance to the United States of America, and to serve them honestly and faithfully, against all their enemies or opposers whatsoever….” Lee did not resign his commission until after Lincoln called for 75,000 troops to put down the “rebellion” and the people of Virginia seceded from the Union. In the mind of most men of the Upper South, Lincoln’s quest to use force to crush secession amounted to a violation of the Constitution and made him an “opposer” and enemy of the States, the “them” in Lee’s oath. The Twitter brigade claims this constituted a violation of his oath. Lee believed he was defending it by refusing to take up arms against his home, his family, and his State. What could be more noble? One Twitter brigade historian stated that, “One does not oppose secession and then take such a dramatic action to fight for…secession.” Lee wrestled with his decision to side with Virginia over the Union, as did many Southerners. To argue otherwise is to show complete ignorance of secession winter and for that matter Lee’s painful decision. Even Pryor, whom all the Twitter brigade loves to cite, agrees. “This poignant moment, when a strong, steadfast man paced and prayed in despair, is a scene worthy of Shakespeare precisely because it so palpably exposes the contradiction in his heart.” Lee was unequivocally opposed to secession right to the point of making the decision to resign from the army and side with Virginia.

But this Twitter historian goes further. He argues that “Lee wanted to protect Virginia, the South, and its ‘institutions…’ and by its institutions he means slavery.” Except Lee never once defended slavery during the War. What did Lee suggest the men of Virginia were fighting for? This is what he wrote in September 1861:

Keep steadily in view of the great principles for which [you] contend and to manifest to the world [your] determination to maintain them. The safety of your homes and the lives of all you hold dear depend your courage and exertions. Let each man resolve to be victorious, and that the right of self-government, liberty, and peace shall find him a defender [emphasis added].

Obviously Lee intended “the right of self-government, liberty, and peace” to mean slavery, slavery, and slavery, and without question “the safety of your homes and the lives of all you hold dear” meant slavery and more slavery. Why? Because obviously every Southerner who had his body blown apart by cannon shot did so because they either wanted to own slaves or did own slaves. The arch neo-Confederate historian James McPherson had this to say about Southern motivation: “The concepts of southern nationalism, liberty, self-government, resistance to tyranny, and other ideological purposes…all have a rather abstract quality. But for many Confederate soldiers these abstractions took a concrete, visceral form: the defense of home and hearth against an invading enemy.” Lee would have agreed, but according to the Twitter brigade, there could be no other explanation other than slavery, the historical record notwithstanding.

And what about the postwar Lee? It has become fashionable to attach Lee to the Ku Klux Klan. Both Serwer and the Twitter brigade suggest that Lee supported the Klan and turned a “blind eye” to Klan activities in both Virginia and Washington College, where Lee assumed the role of president after the War. Pryor is often cited to reinforce the argument. But clearly neither Serwer nor the Twitter brigade read everything she wrote on the matter.

The Lexington Freedman’s Bureau often complained that local residents harassed African-Americans in the community and charged Lee’s students at Washington College with attempting to sexually assault “unwilling colored girls….” One letter–one letter–is used as evidence that students at Washington College “formed a chapter of the Ku Klux Klan” to scare “blacks and whites alike with notices depicting skeletons, coffins, and black crape.” When did one letter become overwhelming evidence of anything?

The fact remains that Lee often took action against racial violence. On one occasion, a former Freedmen’s Bureau teacher named E. C. Johnson was bullied after a “skating party” nearly resulted in a melee. What Pryor and the Twitter brigade leave out is that Johnson perpetuated the violence by pulling his pistol on a young boy and threatened to kill him for the simple act of taunting the man. Northern newspapers picked up the story, and according to the faculty minutes of Washington College, Lee dismissed the students involved. Just prior to this, Lee dismissed a student who admitted to pistol whipping an African-American during an altercation. When the son of a local judge was shot by an African-American after an altercation, several Washington College students participated in vigilante activities aimed at a lynching. The Freedmen’s Bureau contacted Lee to warn him that such activities would be met with a military response. Pryor writes: “Lee had sent out advisories forbidding his students to take part in these activities, and in both instances Lee promised army and city officials that those participating would be penalized.”

That’s not what Serwer and the Twitter brigade argue. Serwer: “Lee was as indifferent to crimes of violence toward blacks carried out by his students…” and one Twitter brigade historian: “Lee turned a blind eye towards and did not punish the students involved…[and] never responded to any of the charges or cooperated with the Bureau to investigate.” Of course, Pryor contradicts herself just two sentences later by claiming that Lee “at best…gave ambiguous signals…” and suggesting that “The number of accusations against Washington College boys indicates that he either punished the racial harassment more laxly than other misdemeanors, or turned a blind eye to it.” Her evidence? One letter from the same student who suggested that the College had a Klan chapter. Which source would be more reliable? The Washington College faculty minutes or a letter from a student to a parent based on hearsay? To the Twitter brigade, clearly the latter, but what can anyone expect from such “scholars?”

Our now infamous Twitter brigade scholar concludes that “the “marble man” myth-[is] an image that has no basis in fact and is easily disproven by the historical record. I mean, this stuff isn’t secret….[and McDaniel’s] assessment of Lee flies in the face of all available historical evidence.”

Using this standard, what does “all of the available historical evidence” tell us?

Lee was a de facto but never de jure slave owner for roughly five years of his life, and for a shade over two years in accordance with the provisions in his father-in-law’s will (the slaves should be freed if the estate was solvent or after five years otherwise) managed the Arlington estate in an attempt to make the property solvent in order to save it for his wife and family after years of mismanagement. This included hiring out slaves to other plantations, but he never sold a single slave or legally broke up a family through a sale. Lee did free several slave women and children at his wife’s insistence before he took control of the estate, and his wife and daughters taught several of the Lee family slaves to read and write even though Virginia law prohibited it. Mary Custis Lee even entrusted one slave with the keys to the plantation when they were forced to evacuate the property in May 1861. Lee rid himself of the responsibilities in December 1862 partly with his own money, worked to keep these freedmen from bondage after the fact, favored enlisting blacks in the Confederate army in return for emancipation, and called slavery a “moral and political evil.” He denied engaging in cruelty three times–once in a private letter in 1859 when he was fully at liberty to speak on the matter–after the abolitionist press attacked his character, and he called executing the Custis will a “miserable legacy.” Is that the collective work of a proslavery ideologue?

Lee thought nullification illegal, privately argued against secession, anguished over his decision to leave the army, and was generally a reluctant Confederate who saw it has his honorable duty to side with his family and State. He wrote he wished Virginia would stay in the Union so he would not have to make such a difficult choice. Had that happened, Lee would have certainly stayed in the United States Army and probably would have accepted Winfield Scott’s offer to lead Union forces. Is that the work of a “fire-eater” like William L. Yancey or Robert Barnwell Rhett?

Lee held views on race that matched what the majority of Americans believed at the time, including many prominent Republicans like Benjamin Wade and Abraham Lincoln, and while president of Washington College after the War dismissed students who engaged in racial violence. He did not support the Fifteenth Amendment–he was not alone even in the North as New Jersey, Ohio, Oregon, and California all rejected the amendment–but publicly spoke of reconciliation and healing and refused to profit from his fame or have his name attached to cause that might stir sectional tension. One postbellum observer remarked that Lee “was bowed down with a broken heart.”

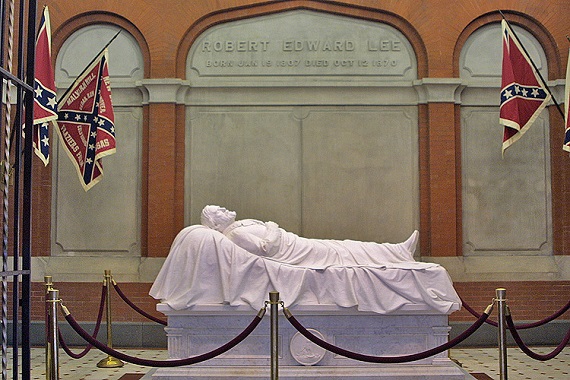

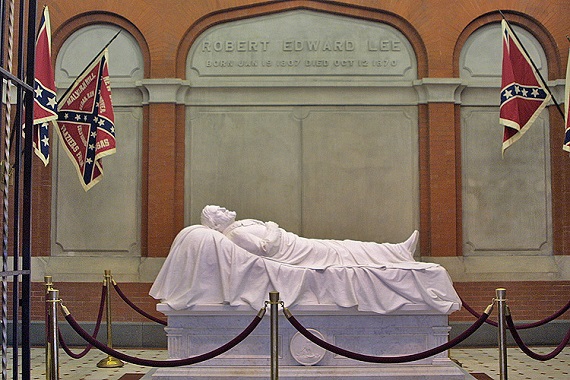

Generations of Americans North and South respected Lee. Like Washington, Lee became the symbol holding the sections together. Northerners like Charles Adams, former Union officer and grandson of John Quincy Adams, admired his honor and integrity, and even into the 1970s, American presidents, both Democrat and Republican, heaped praise on Lee’s character. Dwight Eisenhower argued that “a nation of men of Lee’s caliber would be unconquerable in spirit and soul. Indeed, to the degree that present-day American youth will strive to emulate his rare qualities . . . we, in our own time of danger in a divided world, will be strengthened and our love of freedom sustained…” while Franklin Roosevelt said at the unveiling of a Robert E. Lee statue in Dallas, Texas (since removed by an “enlightened” city council) that “We recognize Robert E. Lee as one of our greatest American Christians and one of our greatest American gentlemen.” Winston Churchill simply said “Lee was the noblest American who had ever lived.”

That’s the real Robert E. Lee. “This stuff isn’t secret.” Perhaps the “amateur” McDaniel is better equipped to discuss Lee than the “actual historians” in the Twitter brigade or at The Atlantic. It wouldn’t be the first time an “amateur” has outclassed them.

One of my favorite pieces