“Lincoln, under no circumstances, would I vote for … So, I say, stand by the ‘Constitution and the Union’, and so long as the laws are enacted and administered according to the Constitution we are safe …“ (emphasis added) Letter from Sam Houston to Colonel A. Daly, August 14, 1860

The 1860 Election was still 3 months in the future and Houston had no inclination to pre-judge the new sectarian party that might be brought to power in Washington City. He was wrapping himself, as he always did, with a Jeffersonian understanding of constitutional liberty and wanted Texas protected by that same banner of Law. He was clear-sighted what might happen but remained a Jacksonian Dreamer. He knew the cherished Union of Jackson and his forefathers. Their dreams embodied his.

In the summer of 1860 he allowed his name to be placed in nomination for the Presidency at the Constitutional Union Party’s convention. He lost to Senator John Bell of Tennessee. Sam was the Vice-Presidential candidate but withdrew his name. There was no reason for him to become the nullity that is the Vice-President’s chair.

Perhaps this fight for the nomination was America’s last chance to avoid war with itself. Houston was hugely popular in the North. One of only two Southern Senators (the other John Bell of Tennessee) to vote against the Kansas-Nebraska Bill eliminating the Missouri Compromise because he knew America would skid to war, many politicians admired his honor, his candor, his understanding of social events, of political windmills and the entrapping growth of America’s reach for greater wealth and power.

Had he won the Presidential nomination, he likely would have lost South Carolina and the Gulf States but the Border States would have been his and the Northern and Midwest States might go for him as well as not. Even Senator Charles Sumner, the premier Radical Republican from Massachusetts, admired him and considered him a more than good prospect for President. But after his loss of the nomination, Sam’s concentration shifted to Texas alone. He abhorred the manufacture of events he saw coming and wanted Texas free, untouched and undamaged in its own land.

VIRGINIA

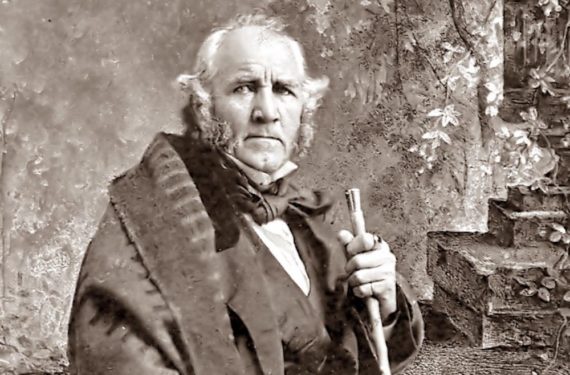

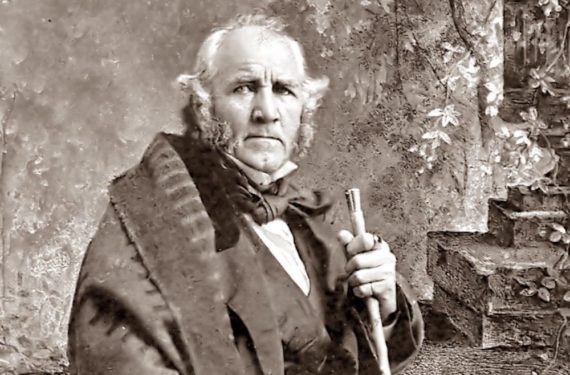

He was born in the Shenandoah Valley of Virginia, Rockbridge County, on March 2 1793. Its capitol, Lexington, would later become the home of VMI and Washington & Lee and remains one of the Valley’s alluring towns. Houston always remembered Virginia as his ‘mother State’. He was raised with a Jeffersonian urgency for a Union reflected among his neighbors and family.

In the spring of 1861, though 1300 miles apart, Houston and Rockbridge would wend the same political road. Both County and its birth son fought secession: Rockbridge with a majority of Virginians, Sam with a minority of Texans. Then Lincoln called for war and Rockbridge with a new majority of Virginians turned against Lincoln’s poetical ‘Union’ and stood for liberty. In Texas Sam Houston did the same.

********

After the death of his father, Sam’s family moved to Tennessee. When old enough, he joined the military and suffered death-spelling wounds under Andrew Jackson at Horseshoe Bend in Alabama. Left for dead on the battlefield, the next morning he was still alive. Among multiple wounds, a rifle ball in his shoulder never entirely healed.

After Horseshoe Bend Houston became a princely protégée of Andy Jackson with a destiny, perhaps, for the Presidency. He studied law under Tennessee Judge James Trimble, a noted Madisonian known for intellectual integrity. Sam found he had a natural passion against party politics. To him it was the good of elites over the good of the people. It was government for and by the elites, not for and by the people. His aversion would remain his entire life.

TENNESSEE

” … I am cheered by the consolatory hope that I shall not look in vain to my countrymen, for that support, which justice and patriotism never fail to afford. … To me it is a source of grateful pleasure, and of manly pride, that Tennessee is my adopted country. [emphasis added]

“One of my obligations is to support the constitution of the United States. …. But at the same time, that we hold that production of our ancestors sacred, we should observe with vigilance, and guard with firmness, our own constitution, (which is the guarantee of our sovereignty whenever an infraction of it is attempted by the General Government. [emphasis added] Thus, while we support the federal constitution according to its essential principles [emphasis in original], with a view to the preservation of the confederacy on the one hand, – we are bound on the other, to watch over, and preserve the rights of the State…” . Inaugural Address of Governor Sam Houston, October 1, 1827 on becoming the 7th Governor of Tennessee. Writings of Sam Houston, Vol. 4, p.9

It is perhaps the shortest Inaugural of any American Governor, a mere 6 paragraphs including salutation and conclusion. Yet it expresses the governmental beliefs of the True Federalist Founders in 1787 – Mason, Martin, Patterson and Gerry; not the Faux Federalists – Morris, Hamilton, Wilson and Madison. Like Jefferson, his country is his State.

Before the rise of Garrison’s malicious abolitionism, Houston saw war clouds drifting among the American States and cautioned that a State’s sovereignty must be defended. He was not looking for war. But he would sustain “the rights of the people” of Tennessee.

Sam was a plain speaking Governor. The wisdom of American compact government he would carry throughout life. He explained to the Tennessee Legislature on October 15, 1827:

“In the legislating for a Government like ours, where many of the most valuable institutions are founded on experiment, the best informed minds could not in the earlier progress of things, determine with reasonable certainty upon the regulations and rules of action best suited to the circumstances of society, and the permanent good of the country. Experience alone can develop the fitness of measures, and the salutary or pernicious influence of particular laws. … and nothing which is not in itself morally wrong, is more to be deprecated in a free country than excessive legislation.

… The necessity of all law grows out of the wants and interests of society, and when these are relieved or defended, we may always rely with much confidence on the virtue and intelligence of the people.” (emphases added) Writings of Sam Houston, Vol. 1, p. 115

These are the hallmarks of Houston’s philosophy: not theory, which grows luxuriant in our intellects only to flounder on the street, but experiences that grow from the “virtue and intelligence of the people”. People are to make the choices of government and for government. How the people wish to govern are the foundational pillars, philosophies and goals of “a free country”. Plainly for Houston, the people are sovereign. Not any design or scheme or political faction.

No caretaker Governor, he led from the wishes of the people. He governed how he always would: an advocate for his State among the Compact of the States. To Houston, “union” under the 1787 Compact meant an enterprise of peace and prosperity for everyone.

Then early 1829, a personal tsunami became his political grave – a strange marriage tumbled him out of Tennessee and 3 years later into the land of Tejas.

TEJAS

“If I were God, I would wish to be more.” Antonio de Padua María Severino López de Santa Anna y Pérez de Lebrón as quoted in Sam Houston by James L. Haley at 100

On December 2, 1832 Sam Houston crossed the Red River into the sovereign Mexican State of Coahuila y Tejas. He meant to remain, build a new life, and probably a new alliance for Tejas. He was baptized as required by Mexican law and entered the tangled bundle of Tejas politics. He arrived from the United States with a reputation for political savvy, bravery in war and being a loyal intimate of Andy Jackson.

Events were roiling in Tejas. By the early 1830’s Anglos were 80% of the Tejas population. They had arrived in the belief they would be living in a federal republic similar to their government in the United States. Few, if any, recognized Mexico’s centuries long experience under a highly centralized government with veritable strong men dictating over the land was a cultural habit a new country cannot easily undo. Mexico had won independence from Spain only in 1821.

Coahuila had a greater number of people but not of Anglos. Language and political history began to take their toll. A cultural conflict was erupting. The vast differences in culture between the two Provinces brought the people of Tejas to determine they should become their own independent, sovereign Mexican State.

A ROAD TO SECESSION FROM MEXICO

Then came General Santa Anna. After electioneering on republican principles in ’33, he would throw the 1824 Mexican Constitution to the wind in ’35. He had portrayed himself an erstwhile friend of democratic republics. They were beliefs he held gingerly and without conviction. He was a fluttering chameleon of the first order: ruthless, charismatic and self-feathered for glory.

In early 1835 Santa Anna stomped on the sovereignty of the States. He replaced the Mexican Constitution with a new set of laws known as the “Siete Leyes” (“The Seven Laws”). He dissolved the Congress and made the States into Departments of the Central Government. He was against Tejas becoming itsown Mexican State.

That woke the banner of rebellion across Mexico. Coahuila y Tejas, San Luis Potosi, Queretaro, Durango, Guanajuato, Michoacan, Yucatan, Jalisco, Nuevo Leon, Tamaulipas, and Zacatecas all rebelled. Santa Anna answered with incomparable brutality. Zacatecas, the best armed and led of the States, was brutally vanquished by Santa Anna on May 12, 1835, his troops let to plunder at will for 2 days. Preening malice became a hallmark of Santa Anna’s dictatorship.

With the exception of Tejas, all the other rebellions eventually folded. Tejas didn’t have the military power of a Zacatecas nor the population and wealth of a Coahuila. But it was the most northern of the provinces and the only one adjoining the United States. It was the only Mexican province overwhelmingly Anglo whose people in very recent years had been American. Faced with Santa Anna’s malice, Tejas sentiment moved from Mexican Statehood to secession.

In late 1835 a shaky, newly cobbled Tejas government named Houston Commander of its army, if such could be called an army.

SEVEN WEEKS AND A DAY TO INDEPENDENCE

“Our proclamation to the other states of the Mexican Confederation, asking them to support us in our struggle for the restoration of our former rights, and for the protection of the Constitution of 1824, have, as you all know, been without results … No other help remains for us now than our strength and the consciousness that we have seized our arms for a just cause. Since it is impossible to call forth any sympathy from our fellow Mexican citizens, and no support is to be expected from this side, and as they let us, the smallest of all the provinces, struggle without any aid, let us, then, sever that link that binds us to that rusty chain of the Mexican Confederation …” “Speech to his Army at La Bahia (Goliad)”, by Sam Houston, January 15, 1836; Writings of Sam Houston, Vol. 8, p. 337 – 338

“When a government has ceased to protect the lives, liberty and the property of the people, from whom the legitimate powers are derived, …

… when the Federal Republican Constitution of their country, which they have sworn to support, no longer has a substantial existence, and the whole nature of their government has been forcibly changed, without their consent, from a restricted Federative Republic, composed of Sovereign States, to a Consolidated Military despotism, in which every interest is disregarded but that of the army and the priesthood, both the eternal enemies of civil liberty, …

… in such a crisis, the first law of nature, the right of self-preservation, the inherent and inalienable rights of the people to appeal to first principles, and take their political affairs into their own hands in extreme cases, enjoins it as a right towards themselves and a sacred obligation to their posterity to abolish such government, and create another to its stead, calculated to rescue them from impending dangers, and to secure their future welfare and happiness …… Unanimous Declaration of Independence (Secession) of the Delegates of the People of Texas, in General Convention, at the Town of Washington on March 2, 1836. Among the signers was Sam Houston. It was his 43rd birthday.

The men and women who died at the Alamo on March 6, 1836 did not know they were dying for Texas independence. The news had not reached them. Santa Anna’s senseless massacre of their lives and the later March 27, 1836 massacre of the 400+ prisoners of war at La Bahia (Goliad) inflamed Houston’s men. Tejas, now Texas, was in a fiery rage.

On April 21, 1836, at San Jacinto Houston rode at the front of his nearly 800 ragtag, hustling soldiery including a few disguised US infantry to defeat a well-trained and experienced Mexican army of over 1300 commanded by Santa Anna himself. Beneath the cries “Remember the Alamo!” “Remember La Bahia!” the battle lasted maybe 18 minutes.

Santa Anna signed a Treaty at Velasco, Texas on May 14, 1836 recognizing Texas independence. But Mexico City refused to accept it preferring to believe Texas remained Tejas. Its mind did not change when Texas entered the United States in 1845. Not until 1848 and the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo did Mexico accept the Rio Grande as the boundary between itself and Texas. But it didn’t really matter. Except for some skirmishing by Mexico in 1842, the fighting was over and governance from Mexico City undone.

THE REPUBLIC OF TEXAS

“A spot of earth almost unknown to the geography of the age, destitute of all available resources, comparatively few in numbers, we modestly remonstrated against oppression, and, when invaded by a numerous host, we dared to proclaim our independence and to strike for freedom on the breast of the oppressor. As yet our course is onward. We are only in the outset of the campaign of liberty. Futurity has locked up the destiny which awaits our people …

… I shall confidently anticipate the establishment of Constitutional liberty …” (emphasis added) Sam Houston, 1st President of the Republic of Texas, Inaugural Address, October 22, 1836, Writings of Sam Houston, Vol. 1, p. 448

For the nearly 10 years of its independence, the Republic was shadowed by danger. When Houston assumed the Presidency in October 1836, there was a Constitution but no settled culture or structure of government. Unlike the American revolutionary army returning to State governments of long historical experience, the Texans now gathered around hardly any government at all.

There wasn’t the bare instruments of government like stationery and a Great Seal. The early Texas politicians were so self-minded that the Senate routinely overrode Houston’s vetoes. Sam’s extensive experience in Washington and Tennessee now was taxed to its limit. Money was scarce and a system of money created. The capitol, Columbia, was a rudimentary town, literally a “barnyard republic”, Haley at 166.

The legislature early resolved to relocate. In April 1837 it moved to the new capitol, a town built just for this purpose by 2 brothers from New York who had emigrated to Tejas a few years before. They named the town ‘Houston’.

Annexation to the American States was now on everyone’s mind. Only the politics of the United States kept Texas at bay. In the 1836 election making Sam President, only 94 Texans voted against annexation. This desire to join the United States remained strong with ebbs and flows until done. After all, it would be like going home.

By the end of Sam’s 2nd term in 1844, Texas annexation was near. The politics in the United States was intense but changing. Three American Presidents – Jackson, Tyler and Polk – together brought the issue to fruition. Europe had begun to either recognize Texas as a separate nation or had some expression of diplomatic relations. Texas might move closer to Europe than would be in America’s interest. Houston worked tirelessly, surreptitiously, openly, cautiously, frustratingly, and sometimes coyly to make annexation come true.

On December 29, 1845 President Polk made good his election promise and signed into law the Treaty annexing Texas into the United States. Sam again became a citizen of the United States. But true to his understanding of the US Constitution, he remained first a Texan and secondly a 1787 Jeffersonian federalist. Despite his devotion to the United States, the liberty of the people of Texas would remain his foremost legal and heartfelt concern. Texas was his country.

THE STATE OF TEXAS

“I do not wish to be sectional. I do not wish to be regarded as for the South alone. I need not say that I am for the whole country. If I am, it is sufficient without rehearsing it here. But, sir, my all is in the South. My identity is there. My life has been spent there. Every tendril that clusters around my heart, every chord that binds me to life or hope, is there; and I feel that it is my duty to stand up in behalf of her rights, and, if possible to secure every guarantee for her safety and security.

“I claim the Missouri Compromise, as it now stands, in behalf of the South.” Senator Sam Houston, speaking in Opposition to the Kansas Nebraska Bill, February 14 -15, 1854. Writings of Sam Houston, Vol. 5, p. 499. Houston and John Bell of Tennessee were the only Southern Senators to oppose the Kansas Nebraska bill.

Among the strangulated vines of conformist American history, Sam Houston has been labeled a forever Unionist, a staunch upholder of Lincoln’s contrived Union. But, unlike Lincoln who was first a politician of and for his party (Whig or Republican) and had a low opinion of everyday people, Sam Houston was first a politician of, by and for the people. Not the amorphous “people” of the 1787 Preamble, but the people of Texas, and prior to Texas, the people of Tennessee. He loved the daily people. He hated the elitist government of political parties (the forever home of Abraham Lincoln).

Sam was always just one of us. For him, we’re all in this together. He would stand with us forever. To him Union always meant a positive good embracing all the States to live and work out their differences so that each could reside in peaceable commerce with one another.

He lived his life on Southern principles: Jeffersonian principles of government and Southern principles of honor: all through a Jacksonian dream of Union. On February 8, 1850, he delivered his “Nation Divided” speech in the Senate to support the 1850 Compromise. It would be a speech printed and read around the country, and more than likely by a recent Congressman from Illinois, Abraham Lincoln.

DENOUEMENT IN TEXAS

But in 1854 came the Kansas Nebraska Bill by Stephen Douglas. The core of this bill was the annulment of the Missouri Compromise. If the Compromise were gone, the people of the new State would decide whether to live with or without slavery. Kansas Nebraska passed in May 1854 and Jefferson’s “fire bell in the night” began to toll.

As Houston (and John Bell) predicted, the North heated up its volume cloaking their racism under the mantle of abolitionism. For social, political, employment and personal reasons, white Northerners wanted no black Americans living among them. Maybe 5% of the North supported the abolitionists. Lincoln was no abolitionist. He hated them.

Though the South had opposed the Compromise in 1819, it had not, as Houston pointed out, agitated for rescinding it in 1854. His vote was based on our history since the Compromise. The South had learned to live with it. The land out West had proved hardly suitable for slavery. Better to let mad dogs lie. Sam was no ideologue. But his vote seriously weakened his political strength at home.

Then in 1857 Dred Scott declared the Missouri Compromise unconstitutional. It correctly saw the Compromise of 1819 was an outside-the-Constitution legislative measure “amending” the Constitution unlawfully. The Missouri compromise had been a preemptive strike against State sovereignty. Exactly Jefferson’s point. Jefferson’s “fire bell” began clanging with such ferocity, America could no longer hear itself.

In 1855 the Texas legislature censured Houston for his opposition vote and in 1857 did not re-elect him for a new term as Senator when his present term would end in 1859. Then in 1859, as events ran pell-mell for disunion in the Deep Southern States, Sam was voted Governor for the first and last time.

THE PAST CANNOT RECOVER THE FUTURE

One of the essential reasons Sam loved the Union was the latitude within the Constitution fostering a harmony among the American States to work out their problems in peace.

But the bedrock of Sam’s American foundation was the well being of Texas. So he fought against secession not because he believed secession unlawful (he did not), but because he saw secession with the sectional Republicans in power as the destruction of Texas and the South. He knew war and knew both North and South. He told Texans and the Southern people plainly that the Northern people were not like them. They would methodically and persistently wage war to the ruination of the Union and the desolation of the South.

1860

When the fatal election of 1860 produced a tightening of the fears he and many others harbored of coming domination by the New England-ravaged North, his Jacksonian heart refused to turn from the bonfire spreading from Washington City. He would play everything till the end of sanity, but not beyond honor. He would explain and explain the rousing dangers rending the fabric of America, exposing the land, especially Texas and the South, to annihilation.

“From the moment of his inauguration, there will commence an ‘irrepressible conflict’ different from that which the party of Mr. Lincoln is based upon. It will be an “irrepressible conflict” between The Constitution, which he has sworn to support, and the unconstitutional enactments and aims of the party which has placed him in power. …

“Let us not embrace the higher law principle of our enemies and overthrow the Constitution: but when we have to resist, let it be in the name of the Constitution and to uphold it. …

“I cannot believe that we can find at present more safety out of the Union than in it. Yet I believe it due to the people that they should know where they stand. Mr. Lincoln has been elected upon a sectional issue. If he expects to maintain that sectional issue, during his administration, it is well we should know it. If he intends to administer the government with equality and fairness, we should know that. Let us wait and see. …

“Here, I take my stand! So long as the Constitution is maintained by the ‘Federal Authority’, and Texas is not made the victim of ‘federal wrong’ I am for the Union as it is.” Letter of Sam Houston to H.M. Watkins and Others, dated November 20, 1860 (emphases added). Houston was replying to some 65 citizens in the Huntsville area who asked for his views.

Houston understood the chords of drama America’s politicians were playing. His “Here, I take my stand!” is the ultimate placement of a man by his conscience inside his covenant with his God. Sam was standing on his Honor. The Constitution was not God to the Christian Houston but his loyalty was to his forefathers who bled and lived and died to bring the Constitutional liberty he and they believed the lifeblood of a just society – to the extent we can have a just society in a continuously imperfect world. For him the Constitution was tangible and kept alive by the necessary compromise among citizens to keep it alive. He had no time for Seward’s self-gratifying “higher law principle” which then and today flowers pretentious moral cover to immoral acts of government and citizenry.

In his Message to the Legislature of Texas, in Extra Session, dated January 21, 1861, Vol. 8, Writings of Sam Houston, p. 249, 250. (emphases added), now governor Houston argued:

“While deploring the election of Messrs. Lincoln and Hamlin, the Executive (Houston refers to himself) yet has seen in it no cause for the immediate and separate secession of Texas. … A majority of the Southern States has as yet taken no action and the efforts of our brethren of the border are now directed toward securing unity of the entire South.

“… Texas, although identified by her institutions with the States which have declared themselves out of the Union, cannot forget her relation to the border States. … Those who ask Texas to desert them now should remember that in our days of gloom, when doubt hung over the fortunes of our little army, and the cry for help went out, while some of those who seek to induce us to follow their precipitate lead, looked coldly on us, these States sent men and money to our aid.

“Their best blood was shed here in our defense, and if we are to be influenced by considerations other than our own safety, the fact that these States still seem determined to maintain their ground and fight the battle of the Constitution within the Union, should have equal weight with us as with those States which have no higher claim upon us, and who without cause on our part, have surrendered the ties which made us one.”

The Alamo, Goliad, San Jacinto were never far from any Texan’s memory. Sam was quick to remind them of the blood that brought them liberty in 1836. They did not bleed alone. When we remember Houston was the former Governor of Tennessee his words take special poignancy. Many Americans who answered the call of Texas for help came from the Border States. Crockett and his group but one example.

In 1861 none of the Texas leaders had been born in Texas. Those folks were still too young. The oldest were early 20’s with their earliest memories being of Tejas or the Republic. Anyone born in the State of Texas was no more than 15 years old. In many social and political ways Texas in 1861 was a youthful adult without long cultural memories of how distinctive Texas could be compared to the rest of the United States. But Sam Houston carried the depth of history in his bones and the honor of history in his heart. He feared Texas losing all it had gained through blood and tears.

“You say that it is reported that I am for secession. Ask those who say so to point to a single word of mine authorizing the statement. I have declared myself in favor of peace, of harmony of compromise, in order to obtain a fair expression of the will of the people. … Mr. Lincoln has been constitutionally elected, and, much as I deprecate his success, no alternative is left me but to yield to the Constitution. The moment that instrument is violated by him, I will be foremost in demanding redress and the last to abandon my ground.

“I still believe that secession will bring ruin and civil war. Yet, if the people will it, I can bear it with them. I would fain not be declared an alien to my native home in old Virginia, and to the scenes of my early toil and triumph in noble Tennessee. I would not of my own choice give up the banner beneath which I have fought, the Constitution which I have revered, or the Union which I have cherished as the glorious heritage bequeathed to me by my fathers. … the recollection of past triumphs, and past suffering, the memories of heroes whom I have seen and known, and whose venerated shades would haunt my footsteps were I to falter now, may, perhaps, have made me too devoted to the Constitution and to the Union, but be it so. Did I believe that liberty and the rights of the South demanded the sacrifice, I would not hesitate. I believe that far less concession than was made to form the Constitution would now preserve it. Thus believing I cannot vote for secession. …” (emphases added)–Extract from a Letter by Sam Houston printed in The Southern Intelligencer (Austin) published on February 20, 1861. Writings of Sam Houston, Vol. 8, p. 263 – 264. The newspaper did not disclose the name of the recipient and actual date of the letter.

On January 28, 1861 the Secession Convention began and on February 1, adopted an Ordinance of Secession for the people to vote for or against on February 23. If approved, the Ordinance would take effect March 2, Houston’s 68th birthday. (It is an historical oddity that Texas seceded from Mexico on March 2, 1836, Sam’s 43d birthday, and exactly 25 years later on March 2, 1861, Sam’s 68th, seceded from the United States, the secession vote of the citizens of Texas taking effect that day.)

On February 6, Houston asked the legislature for funds to create a sufficient militia to safeguard Texas should the people vote for secession leaving Texas unprotected after national troops would withdraw if secession became a reality. On February 9 he issued a Proclamation establishing the procedures for the secession vote to take place.

Texans knew where he stood. With great urgency Houston campaigned to support the new Republican Administration arguing Texas had no reason yet to secede. He understood Northern culture. New England was the intellectual and spiritual mother of the North. Its commerce and governments, its daily rituals of living were wrapped in seamless beliefs of their own god-chosen superiority. The Central Government under Northern control without a Southern brake would relentlessly remain sectional. It would veer to war to secure their economic enterprise and civic religion. It would mean the dimming of the Southern sun.

If Texans were to secede, he wanted Texas to again stand alone. Never be part of the Confederacy. He would argue for Union so long as there was compliance within the Constitution. If Lincoln were to go outside the Constitution, he would sanction secession. He told Texans he believed in States’ rights as they did. But he was for Texas more than the South and for Texas more than the Union.

On February 23, 1861, for the 2nd time in 25 years, Texans voted for secession, the vote 46,129 to 14,697. Houston was upset at the vote. He realized, as did many others, that the secessionists had threatened and did bring violence against Unionists. Perhaps only one-third of all voters went to the polls. Yet everyone believed the vote for secession was the will of the majority of Texans. Sam accepted the people’s will.

What he did not accept was the Secession Convention tying Texas to the Confederacy, nor that without approval of the Legislature, the Convention voted to require all Texas officials to pledge loyalty to the CSA. That oath was to be taken on March 16, 1861.

Sam argued strenuously the people of Texas had voted for independence but not to join the Confederacy, and not for their elected officials to take an oath of loyalty to a foreign entity. Neither did he accept the Secession Convention sending delegates to the Confederate Constitutional Convention. He could accept secession but not loyalty to, in his words, a “so-called Confederacy”.

Indeed, on receiving notice from the CSA Secretary of War that delegates of Texas had been seated in Montgomery and Texas brought into the Confederacy, and that “the President of the Confederate States assumes control of all Military Operations” in Texas, Houston, on March 13, 1861, still the sitting Governor, made clear that the Texas Secession Convention had outrun their authority by sending delegates to be seated at the CSA Constitutional Convention in Montgomery.

“The people of Texas by their vote on the 23rd Ult., having severed their connection with the United States, Texas on the 2d day of March, the present month, assumed once more the position of a Sovereign and independent State. No act of the people since that period, and certainly none anterior to it, has warranted the construction that Texas is other than independent. … your letter’s statement that “the President of the Confederate States ‘Assumes control of all Military Operations in this State’ is erroneous. …. Texas’s position before the world, and especially in relation to the Confederate States, seems to be misunderstood.” (emphasis added) Letter to LeRoy Pope Walker, CSA Secretary of War, dated March 13, 1861. This letter was sent by E.W. Cave, Secretary of State for the State of Texas, by direction of Governor Sam Houston.

But Sam was whistling in the wind. Texas would abide by the Secession Convention’s delegates to the CSA. On March 16, Sam and the peaceable, prosperous world of Texas came to a sudden halt. With breaking heart, Sam appealed directly to the People of Texas. He is worth quoting at length.

“I have declared my determination to stand by Texas in whatever position she assumes. Her people have declared in favor of a separation from the Union. I have followed her banners before, when an exile from the land of my fathers. I went back into the Union with the people of Texas. I go out from the Union with them; and though I see only gloom before me, I will follow the ‘Lone Star’ with the same devotion of yore.

” … I refuse to take this oath…. I am ready to be ostracized sooner than submit to usurpation. Office has no charm for me that it must be purchased at the sacrifice of my conscience and the loss of my self-respect.

“I love Texas too well to bring civil strife and bloodshed upon her. To avert this calamity, I shall make no endeavor to maintain my authority as Chief Executive of this State, except by the peaceful exercise of my functions. When I can no longer do this, I shall calmly withdraw from the scene, leaving the Government in the hands of those who have usurped its authority; but still claiming that I am its Chief Executive.

“… I have seen the patriots and statesmen of my youth, one by one, gathered to their fathers, and the Government which they created, rent in twain; and none of them are left to unite it once again. I stand the last of my race, who learned from their lips the lessons of human freedom. I am stricken down now, because I will not yield those principles, which I have fought for and struggled to maintain. The severest pang is that the blow comes in the name of Texas. I deny the power of this Convention to speak for Texas. I have received blows for her sake, and am willing to do so again. (emphasis added) To The People of Texas, March 16, 1861, Writings of Sam Houston, Vol. 8, p. 275, 277, 278

*******

On this lesson of history, Sam was not whistling in the wind. He carried the depths of history in his bones. He had known many of the early leaders of America, if not personally then working close by. He was not merely a political scion of Andy Jackson. Before taking his seat in Congress for the first time in 1824, he visited Jefferson in late 1823 at Monticello with a letter of introduction from Jackson in hand. We have no record of their conversation but do have Jackson’s introductory letter. When he took his congressional seat, Clay was Speaker, John Randolph was a political lion in the House, Daniel Webster stood at the oratorical fore in the House, Calhoun was in steady bloom and Jackson himself sat in the Senate preparing to run for President that same year. Monroe was still President and John Quincy Adams was Secretary of State. Jefferson and Madison and John Adams were still alive. A sense of personal honor was still alive in America, not only in the South but in most every community. At a young age Sam had absorbed his patterns of honor from his family and communities in Virginia and Tennessee. Those patterns, laced with loyalty, were threaded throughout his life.

In those days America still retained an entirely human and almost familial feeling. They were absorbed person to person, in intimate and personal clusters talking, listening, discussing and debating. A man was quickly noticed if he did not honor his word and beliefs. Now in 1861 all those great men of his youth were gone.

It comes into everyone’s life to face alone the unknown future without your forebears. That future comes upon us looking like oblivion. There we wish and dream to Heaven for our posterity. Now it was Sam’s turn.

BEREAVEMENT IN TEXAS

On March 16 Sam went to his office in the basement of the Capitol building and began to whittle. He was an inveterate whittler all his life. It was consolation and a task of composure. Above him R.P. Brownrigg, Secretary for the Convention, began calling the names of Texas officials to come forward and take the oath to the Confederacy. Three times he called the name “Sam Houston”. Three times Sam remained silent, composed and in place. He was then removed from the Governorship. Sam rose and quietly walked home.

In the dark of evening on March 19, the Houstons gathered with friends helping them pack to leave. Having finished the task, they were now conversing “in the dim light of a single candle when a knock came on the door. Seeing armed men without, all within the Mansion believed that the Convention had sent an order that the building should be immediately vacated.” But that was not their message at all. The message was far more radical. The men had come to tell Sam that they and many others were offering their arms and support to reinstate him as Governor.

Sam was outraged: “My God, is it possible that all the people are gone mad? …. would you be willing to deluge the capital of Texas with the blood of Texans, merely to keep one poor old man in a position for a few days longer, in a position that belongs to the people? No! No! Go tell my deluded friends that I am proud of their friendship, of their love and loyalty, and I hope I may retain them to the end. But say to them that for the sake of humanity and justice to disperse, to go to their homes and to conceal from the world that they would have been guilty of such an act.” Printed in The Galveston Daily News, April 3, 1892, on information provided by one of the friends with the Houstons that evening. Writings of Sam Houston, Vol. 8 p. 293

Neither Sam nor Margaret ever revealed a name of anyone in this aborted effort at violence. Whoever they were, they were not alone hoping to keep Sam in office.

Lincoln had just been inaugurated and understanding Houston to be a staunch Unionist offered him military support to keep Texas in the Union. Sam refused. His closest friends advised him to refuse and though he mused that if 10 years younger, he would accept, the telling truth is that he would never engage a war where Texans would be killing Texans. Secession was his last great political battle and he lost. His life’s work to create and keep Texas free left with that vote of the people.

THE LOST AND LAST SENTIMENT OF UNION

At Galveston, with Sumter but 6 days earlier, Houston turned to face the garish winds of war. “He declared that Mr. Lincoln had been precipitate and foolish in steps that he had taken. He should have let the South alone. He again counseled unity of action, and to repel the enemy.” Speech at Galveston, April 19, 1861, Writings of Sam Houston, Vol. 8, p. 300, 301

True to his word, he would stand now with Texas and the South against the manacles of a Sectional Party’s greed and usurpation of power. The Constitution had been upended.

“The mission of the Union has ceased to be one of peace and equality, and now the dire alternative of yielding tamely before hostile armies, or meeting the shock like freemen, is presented to the South. Sectional prejudices, sectional hate, sectional aggrandizement, and sectional pride, cloaked in the name of the Government and Union, stimulate the North in prosecuting this war. Thousands are duped into its support by zeal for the Union, and reverence for its past associations; but the motives of the Administration are too plain to be misunderstood.

“The time has come when a man’s section is his country. I stand by mine. All my hopes, my fortunes, are centered in the South. When I see the land for whose defence my blood has been spilt, and the people whose fortunes have been mine through a quarter of a century of toil, threatened with invasion, I can but cast my lot with theirs and await the issue.

“… Now that not only coercion, but a vindictive war is about to be inaugurated, I stand ready to redeem my pledge to the people. Whether the (Secession) Convention acted right or wrong is not now to be considered. I put all that under my feet, and there it shall stay. Let those who have stood by me do the same, and let us show that at a time when peril environs our beloved land, we know how to be patriots and Texans.” Speech at Independence, May 10, 1861, Writings of Sam Houston, Vol. 8, p. 301-303 (Emphases added)

Now we understand why conformist historians, academics and journalists have clipped the ‘Houston after Sumter’ from the ‘Houston before Sumter’. Here isn’t rhetoric of internal improvements, tariffs, States’ Rights, or any of the other valid assertions by leaders of the Confederacy.

Here is undiluted courage speaking for the people to the Heavens about clear greed, the aggrandizement of power, the duplicity of mercantilist political leaders, especially, though unnamed, the Republican Party’s self-exalting power grab under camouflage of Lincoln’s poetry of deceit. They would bring war which of itself broke the Constitution. Sam was talking from the graves of his forefathers against the damnation of America by the Republican Party’s sectarian North. There was nothing else to plead for … everything till death to fight for.

BATTLEFIELDS OF THE HEART

Sam knew he was too infirm to be useful on a battlefield. And though he and Margaret wished otherwise, Sam, Jr., decided he must join the fight. On May 22, 1861, Houston wrote his eldest child: “Do you, my son, not let anything disturb you; attend to business, and when it is proper, you shall go to war, if you really wish to. It is every man’s duty to defend his Country; and I wish my offspring to do so at the proper time and in the proper way. We are not wanted or needed out of Texas, and we may soon be wanted and needed in Texas. Until then, my son, be content”.

2 months later, on July 23, 1861, he again entreated his son to remember Texas and instructed him their loyalty was to Texas first, Texas last, Texas forever. Houston was willing to die for Texas though not “without hope of benefit”.

“…If Texas is attacked she must be in her present isolated condition. She can look for no aid from the Confederacy, and must either succumb or defend herself … Has she arms, men, ammunition, in an emergency to defend herself? Arkansas is crying for help. Our frontier is again assailed by the Indians and she (Texas) will be left alone in her straits and without means. … I am ready, as I have ever been, to die for my country (Texas), but to die without a hope of benefit by my death is not my wish. The well-being of my country (Texas) is the salvation of my family; But to see it surrendered to Lincoln, as sheep in the shambles, is terrible to me.

“… These matters, my son, I have written to you, and have to say in conclusion, if Texas did not require your services, and you wished to go elsewhere, why then all would be well, but as she will need your aid, your first allegiance is due to her and let nothing cause you in a moment of ardor to assume any obligation to any other power whatever without my consent. If Texas demands your services or your life, in her cause, stand by her ….” (emphases added)

Young Sam enlisted in the 2d Texas Infantry Regiment under his father’s old friend, Ashbel Smith. Both Smith and young Sam were wounded at Shiloh. Like his father at Horseshoe Bend, it was thought he would soon die. Like his father he fought death till found by a minister from Grant’s army walking the battlefield who thought he saw movement in Sam, Jr.’s body. He searched the knapsack hoping to identify the soldier. He found a Bible with the inscription: “Sam Houston, Jr., from his mother, March 6, 1861.” The minister asked the youngster if he was related to Sam Houston and the young man murmured he was.

This minister admired Houston’s opposition to the Kansas Nebraska Bill. He had with 3000 other Northern ministers petitioned Congress not to pass the bill. When accused in the Senate by Stephen Douglas that their petition was mixing religion and politics, Houston, fending off Sumner, had risen to defend their right to petition arguing it was no conflict between religion and government and the ministers had civil rights separate and beyond their religious status.

Realizing this was the son of a man he greatly admired, the Reverend took careful pains to get Sam, Jr. to the field hospital and on his way to recuperation. Sam, Jr., would eventually recover and in September 1862, in a prisoner exchange, he arrived home in Texas.

****

“The time has been when there was a powerful Union sentiment in Texas, and a willingness on the part of many true patriots to give Mr. Lincoln a fair trial … These times have passed by … Mr. Lincoln and his cabinet have usurped the powers of Congress, and have waged war against the sovereign States, and have thereby not only absolved the States, but all the people from their allegiance to his government, the Federal Government having ceased to exist by his acts of usurpation. He has through his officers, suspended the writ of habeas corpus, the bulwark of American liberty, and proclaimed martial law in sovereign States. If I am to rely upon the current intelligence of the day, he has … proclaimed martial law in Missouri, and assumed the civil administration of the affairs of that State, thereby ignoring the Constitution, and setting at naught the sovereignty of the people; and who has, in fact, with more than Vandalic malignity and Gothic hate, sought to incite a servile insurrection in that State. If the last feather has been wanting to break the camel’s back, this act of atrocity would have supplied it. (Underlined emphasis in original, bold emphasis added) Letter of Sam Houston to the Editors of The Civilian and Galveston Gazette, September 12, 1861 Writings of Sam Houston, Vol. 8, p. 313 – 314.

The Spirit of filial Union, once so closely and proudly held by every American, vanished with the War of 1861. The Great Elide of American History: the changing definitions of “Union”, a non-legal word, undefined, so often re-molded to the uses of systemic politicians, became the banner of desolation across America. Washington City by force of arms turned our American pride into doubt, anger, desolation and, finally, artificial glory. A government of merely men had woken in America. Sam Houston would have none of it.

OLD SOLDIERS DO FADE AWAY

“Let his monument be in the hearts of those who people the land to which his later years were devoted. Let his fame be sacredly cherished by Texans, as a debt not less to his distinguished services than to their own honor of which he was always so jealous, and so proud.” (Emphasis added) An Editorial Appreciation of Houston, July 29, 1863, the Tri-Weekly Telegraph (Houston) in Writings of Sam Houston, Vol. 8 p. 349.

Sam’s final years were spent in a long ago dream for Texas to become again a separate Republic. He had little following. His family attests that after being ousted from office, March 16, 1861, Sam’s health began a noticeable decline. He would give his last public speech in the city of Houston on March 18, 1863. He was then 4 months from death. His mind remained clear and his hopes unbent.

He spent his days with his family and his friends. He eschewed political office. Life was beginning to dim. His dream of an independent Texas was lost and he knew it. The war had hardened people’s feelings and any talk against the Confederacy could meet a violent reaction. He complained of Confederate detectives arriving to question his loyalty. For his own safety Margaret and his friends did not encourage his dream of an independent Texas. Silently he accepted and understood their silence.

When he learned that Yankee POW’s were being held in the penitentiary at Huntsville, he went to see them. The penitentiary had never been meant for POW’s and Houston was always grateful to Yankee soldiers who had helped his son return home. When he found them “confined like common criminals”, Haley at 408. He vehemently protested to the Superintendent, a long time friend. To ease the situation, the Superintendent took some of the POW’s into his own home and placed others in homes around Huntsville till an exchange could be arranged.

His health worsening, Sam put his affairs in order. He wrote his Will on April 2, 1863. Memories were overtaking his hours. Texans knew his end was coming. A group of Native Americans cheered him by singing some of their songs he loved. Their visit gave him a final chance to speak their language he loved.

In early July pneumonia took hold of his lungs. Offered a brisk drink of brandy to help fortify his health, he refused. He had given up both drinking and cursing for Margaret. And she was foremost forever his heart … and in his mind.

HER SAM, HIS MARGARET

“Last night I gazed long upon our beauteous emblem the star of my destiny … Forever thine own, Esperanza”. (Underline in original)

Margaret’s first letter to Sam dated July 17, 1939. After their first meeting Sam had stayed several weeks in courtship. He had given her the name ‘Esperanza’, Spanish meaning ‘the one hoped for’.

They were star-blest, star-spurred lovers from the moment their eyes met and thereafter never lost sight of each other. Everyone present that evening saw it. But Margaret did keep something hidden from Sam.

After the battle of San Jacinto in 1836, Houston had been taken to New Orleans for better medical treatment. Asked to give a speech upon the arrival of his ship, he talked to a gathering crowd that included a young, 16 year old Margaret on a school excursion from Alabama. As he was speaking she turned to a friend and said she had a strange feeling she was somehow attached to this man. Margaret was prone to psychic insights throughout her life. Yet on their first meeting 3 years later, she did not confide in Sam her insight their lives would somehow be linked.

At her brother Martin’s home, Spring Hill, just outside Mobile, in the Spring of 1839, their first hours together, Sam took Margaret for a moonlit stroll in the azalea garden. There was a singular, distant star in the evening sky and he told her it was their Star of Destiny. “He asked Margaret to gaze at it after he was gone and let it remind her of him and the lone star emblem of Texas”. Star of Destiny, The Private Life of Sam and Margaret Houston, p. 19, by Madge Thornall Roberts, their great-great granddaughter.

They would marry in Alabama in 1840 and during the next 23 years lived each day within a transformational love that astounded Sam’s old friends, near all of whom forecasted disaster for Margaret. Apart as much as together because of Sam’s political life, they lived in their hearts together and corresponded often. Both were capable poets who exchanged letters of intense attachment to each other, their family and their God. Now in July 1863 their life together in this world was coming to an end. Their family best tell their final moments.

“By her husband’s bedside, Margaret opened the Bible to the fourteenth chapter of John. She began to read: ‘In my Father’s house are many mansions; if it were not so, I would have told you. I go to prepare a place for you.’ Maggie (their second daughter) later wrote about that sad day:

“‘… we heard his voice in a tone of entreaty, and listening to the feeble sound, we caught the words, “Texas! Texas!” Soon afterward my mother was sitting by his beside with his hand in hers, and his lips moved again. “Margaret”, he said, and the voice we loved was silent forever. As the sun sunk below the horizon, his spirit left this earth for a better land.’

“Houston’s last thoughts were of the two things he loved the most in this world. Shortly before six on the afternoon of Sunday, July 26, 1863, Houston and his beloved Margaret were separated by death. Margaret prayed that God would make her children men and women worthy of their father. Perhaps she was remembering earlier in their marriage when Houston had told her: ‘If I leave no other legacy on earth but love and honor, they shall stand and remain pure and unsullied as the moon beams which play around our cottage home.’ She removed the simple gold ring that Elizabeth Houston (Sam’s mother) had placed on her son’s finger more than fifty years before. Margaret held the ring so that her children might see and be inspired by the word that their father had carried with him throughout his adult life. It was ‘Honor’.” Roberts at 323 – 324

Forever circled by their ring of Honor, Sam was gathered to his forefathers to await Margaret’s return to him on December 3, 1867.