I need to tell you one story in order to tell you another.

The Czechoslovakian composer Antonin Dvorak moved to the United States in 1892, and immersed himself in American music while composing his New World Symphony. Although he was fascinated, inspired, and moved by traditional Southern folk music, Dvorak complained that he simply couldn’t tell the difference between Scottish music and Negro music. Wait, what? How could a professional musician and composer get those two things mixed up? The answer, of course, is found hiding behind our 21st century misconceptions as to what 19th century music must have sounded like. And most Americans have a terrible tendency to separate Southern musical culture into social and political categories, which leads to obviously ridiculous contradictions.

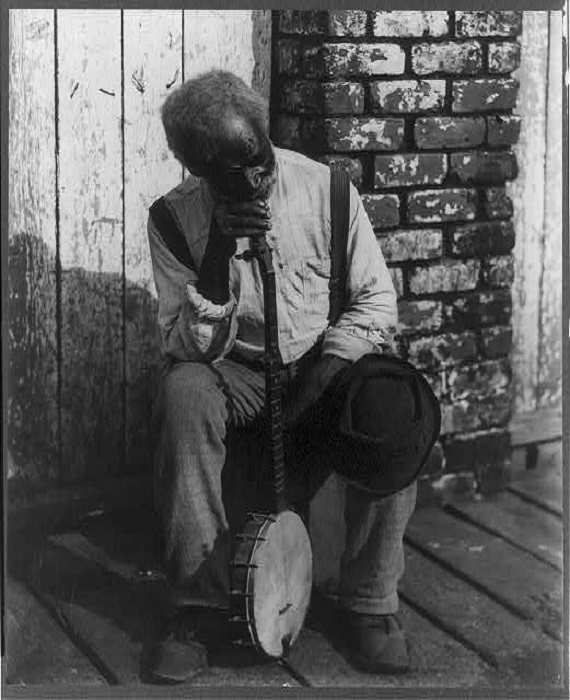

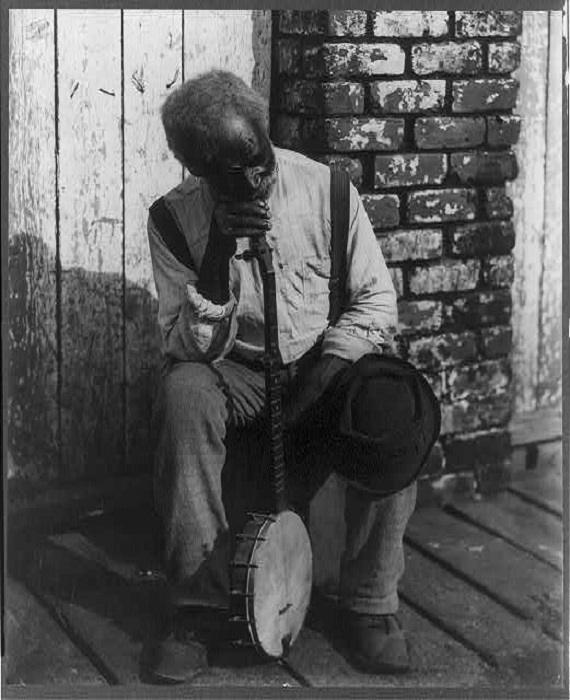

For example, the banjo (and banjo music) is a phenomenon that in contemporary times is associated with poor rural Southern whites. Hillbillies. Rednecks. Good ole boys. However, the banjo is actually a West African instrument. The concept behind the banjo was brought over in the slave trade in the 17th century, and early slaves constructed them out of hollow gourds, animal skin, and sticks of wood. It was the slaves who taught the banjo to the whites.

Probably the earliest known depiction of a banjo in American culture is a painting called The Old Plantation by John Rose from about 1790, and it depicts a slave string band (the instrumentation would vary, but a string band usually featured a fiddle, a banjo, and percussion). African American string bands were numerous and successful throughout the South in the 19th and early 20th centuries. Therefore, original and traditional black music in America always featured the sound of the banjo.

Consider a modern-day string band called the Carolina Chocolate Drops. They are not an historical anomaly or anachronism. They play authentic string band music as taught to them by one of the last-surviving experts, Joe Thompson. Some of their songs are old and traditional, while others are modernized into the 21st century. This one is Sourwood Mountain. (begin at 0:24)

That is what authentic Southern black music sounded like in the 19th century. Remember the poor composer Dvorak, who couldn’t tell Scottish music and Negro music apart? After hearing the Carolina Chocolate Drops, can you blame him?

Now, I have presented here at Abbeville on several occasions my contention that all American music is actually Southern music. If that is true, then I should be able to identify the common thread of musical DNA that runs through everything. And I can. It’s called the Scotch snap.

Musically, the Scotch snap is an identifiably unique rhythm heard originally in Scottish strathspeys, and it consists of a short, accented (strong) note followed by a longer, unaccented (weak) note. It’s a rhythm that you might think of as being two lightning-fast notes. As you watch the following instructional video, find the notes that she plays which will fit the word “Bonnie” when pronounced crisply. These are the first two notes in each phrase, and those two notes are the Scotch snaps. You only need to watch about a minute in order to get the idea. (begin at 1:18)

This next video is an example of an actual strathspey that happens to be loaded with Scotch snap rhythms. See if you can find them by listening for that crisp little two-note “snap.” (begin at 0:37)

Now, skip ahead to the year 2019, and see if you can find the Scotch snaps in this Ariana Grande song. That’s right – Ariana Grande. If you need help, the Scotch snaps occur every time she sings the words “see it,” “like it,” “want it,” and “got it.” Don’t worry – about 20 seconds is all you’ll need in order to get the idea. (begin at 0:51)

Could you hear it?

As it turns out, the Scotch snap rhythm that originated in traditional Scottish folk music comes directly from the spoken English language. The only way to correctly pronounce all of the following English words is with a Scotch snap – “uncle, pretty, basic, running, jumping, hitting, Peter, Phillip, David, English, Scottish, Irish,” etc. The vast majority of two-syllable words in the English language require a Scotch snap for correct pronunciation. And since lyrical music is based on the spoken language, then Scottish music follows a Scotch snap pattern as well. Moreover, since the Scotch snap is unique to English, then the Scotch snap is unique to the music of English-speaking cultures. It is not found at all in German or Latin-based Romance languages, such as French, Italian, or Spanish, since none of those languages contain a Scotch snap in their speech patterns. Therefore, it is not found in their music.

Southern music is an English-speaking art, and every genre of Southern music is loaded with Scotch snaps. But wait, aren’t Nordic languages like German more similar to English than Romance languages? How does that work? Romance languages have a different trademark rhythm, and since German vocal music is heavily influenced by Italian vocal music, then all German music is noticeably similar to Italian in rhythm, and lacking in Scotch snaps. Conversely, Scotch snaps are found throughout the music of any culture that speaks any derivation of English (such as Gaelic), and that includes the English, the Scottish, the Irish, and the Welsh.

Now, what does all that have to do with Southern music? In 1800, the U.S. population was 80% British, and up until 1890, well over half of all immigrants to the Unites States were from England, Scotland, Wales, or Ireland. Also, almost all of the Scots-Irish immigrants managed to find their way to Appalachia (especially after the England-Scotland Union of 1707). In 1916, the British musicologist Cecil Sharp concluded that there were more original English folk tunes to be found in Appalachia than in England. There is no question that Appalachian folk music is loaded with Scots-Irish influence. And while the population demographics of Appalachia favored Scots-Irish immigrants and descendants, the black population of the South was focused along the coastal regions and the plantations. However, there was a wide collar-shaped buffer zone between Appalachia and the coastal region where Scots-Irish whites lived and blended their culture with African slaves. This overlap and co-existence of Scots-Irish and African culture lasted for well over 200 years in the South, and is the very reinforced concrete foundation of all modern American music.

Scottish music already had the Scotch snap. And since African American music was based in the English language, it couldn’t help but pick up the Scotch snap, too. And on and on and on. Every lovechild of every genre of Southern music passed that same Scotch snap down to its musical descendants, where it continues to flourish to this day. In fact, one of the current trademark sounds found in rap and hip hop today is the good old Scotch snap. It’s all over the place. Once you know what to listen for, it’s easy to find. However, you should probably brace yourself for some intensely graphic lyrics if you decide to go searching.

While you’re at it, listen to Elvis, Louis Armstrong, Muddy Waters, Hank Williams, Earl Scruggs, James Brown, Singin’ Billy Walker, Lynyrd Skynyrd, Scott Joplin, Bob Wills, and every other Southern musician you can think of, and you’ll easily hear the Scotch snap regardless of genre.

So, what happened to cause the banjo and its music to be inaccurately disassociated from black culture and cemented to poor Southern white culture if they share the same roots? In my Music Appreciation classes, I always feature a symphony by the African American (and Arkansas native) composer William Grant Still called the Afro-American Symphony (1930), which famously includes the banjo in the orchestra. As soon as I play the banjo excerpts for the class, several students will express distaste for the sound, even though Still was being historically accurate in his instrumentation choices. They can’t really tell me WHY they don’t like it, but they just know they don’t. Well, I do know why. And we can blame most of it on Yankees for creating this unfortunate cultural separation in the music.

I certainly don’t approve of this in Southern music, but I know where it came from. I don’t agree with it, but at least I understand the origins. Basically, it came out of the Civil Rights Era, as African Americans sought to claim a collective identity to which they had been historically denied. And I understand that. I get that. Yet, when we study Black History Month, we don’t learn about the great black real estate barons of early Manhattan, or the powerful black railroad barons of the 19th century, or the bold black investment bankers of the early 20th century. No, the further back we go, the more limited we are to sports, literature, and music. And, as it turns out, music is extremely easy to separate into racial categories, making it an easy victim of this kind of musical apartheid.

To practice musical apartheid ignores all the evidence that Southern music is much more hybrid than practically everything else about Southern culture. Yet, for marketing purposes, almost all of our contemporary Southern music is divided into racial categories. Rap music is marketed towards black audiences, and Country music is marketed towards white audiences. After enough of this nonsense, we tend to associate the targeted population with the music. Country music makes us think of “those people,” and Rap music makes us think of “those other people,” when the reality of the music is much different. If Southern music is truly divided by race, then how do we explain the exploding popularity of the country hip-hop duo known as Florida-Georgia Line? Are they simply a bunch of white kids who badly want to be black? Of course not. Time and time again, empirical research verifies that socio-economic status is a MUCH more reliable variable than ethnicity in every branch of the behavioral sciences. In other words, we would understand Southern music better if we thought of it in terms of class rather than race. And the ultimate “class” that defines the basic DNA of Southern music are the Scots-Irish.

However, outside of the South, this musical apartheid is the only reality they know. To Yankees, American music and Southern music have ALWAYS been racially divided. It has always been either Black or White. However, to those of us actually making the music and living the music, it has NEVER been Black or White. It’s just Southern. We know that the music is blended, but the Yankees really don’t have a frame of reference for that, so they constantly try to separate it out into the individual ingredients.

And of course, we’re the ones who are being naïve. We poor, dumb Southerners need those intelligent, enlightened Yankees to save us from ourselves once again. We need them to teach us what the South is really like, and blah blah blah blah blah. Same old, same old, same old nonsense, over and over again.

It must be exhausting for them to continually and habitually deconstruct Southern culture, especially when they have none of their own. But after a hard day’s work of rewriting Southern history, they can at least sit back and enjoy some good old American music that features a strong backbeat, some soulful blue notes, and long, melismatic vocal runs. Except that all those things come from Scottish music, too.

But that’s a story for another day.