A serial review of books numbering the States after a dissolution of the Union.

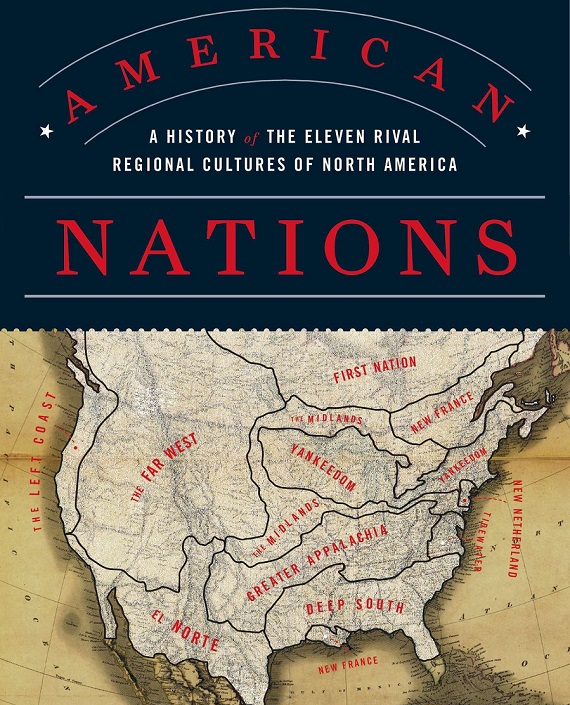

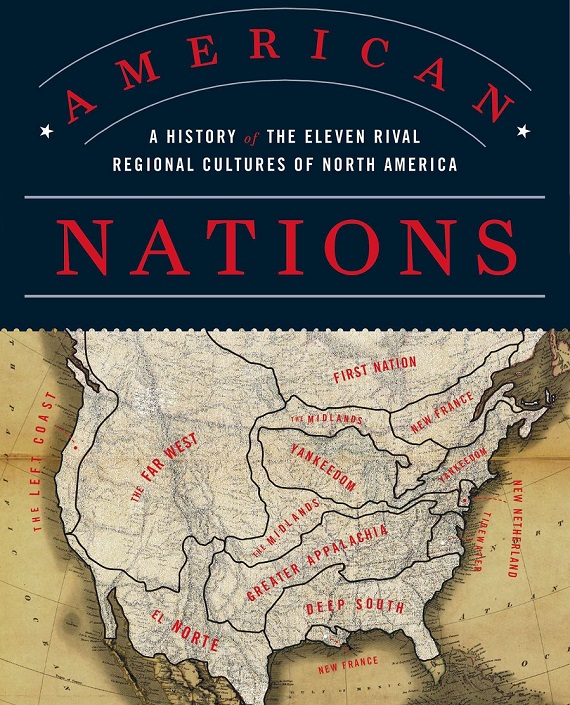

American Nations: A History of the Eleven Rival Regional Cultures of North America by Colin Woodard; ISBN: 978-0-14-312202-9, Penguin, September 25, 2012, 384 pages.

American Nations is simply the most brilliant book I have ever read on American history. Almost every page is compact with some idea that overthrows “what every schoolboy knows,” and like every original and seminal book, it flows from a single powerful idea – in Woodard’s case, the idea that an American Union never existed. There are no “mystic chords of memory” swelling the chorus of Union except in the bombast of Lincoln’s rhetoric; there is no happily jiggered tumult of democracy pace Howard Zinn, where everyone eventually votes to slice off his chunk of the commonwealth; there is no “melting pot”; no “American exceptionalism”; no “propositional nation.” Woodard states at the outset:

There isn’t and never has been one America, but rather several Americas. (p2)

Given the political climate prevailing even at the time of his writing, Woodard must tread carefully in his definition of “culture.” He rejects the term “state,” a purely political entity, for his eleven groupings, but accepts “nation” as fully interchangeable:

A nation is a group of people who share – or believe they share – a common culture, ethnic origin, language, historical experience, artifacts, and symbols. (p3, Woodard’s emphasis)

The term “ethnic” is not explosive if handled properly, but the keg of dynamite rolling about the room is the business of “race.” After defining his eleven regional cultures, he notes that other nations, in that nasty old Europe, have race-based identities – and assigns that danger to a footnote, slipping in the word “usually” for our race-free varieties:

becoming a member of a nation usually has nothing to do with genetics and everything to do with culture. One doesn’t inherit a national identity the way one gets hair, skin, or eye color; one acquires it […]. (p18, Woodard’s emphasis)

The defining characteristic for each of the eleven cultures, or nations, stems from the culture of their founders – a characteristic that survives in each, he claims, even when the primal history is forgotten.

Yankeedom begins in 1620 with the Pilgrim separatists from the Anglican Church in Cape Cod and Connecticut, and in the 1630s with the Puritan non-separatists in Massachusetts. It is not true, “as every schoolboy knows,” that the Puritans came to establish religious freedom. Unlike the Pilgrims, they were a “Calvinist theocracy” (p57) and “a genuinely revolutionary society” (p58) where each member was carefully watched for his conformity in creating the New Zion. Any dissent was met with mutilations (slitting nostrils, cutting off ears, brandings) or with death, even “for infractions such as adultery, blasphemy, idolatry, sodomy, and even teenage rebellion.” (p58) Their elites were not aristocrats – they secured their royal charter by fraud – but highly educated individuals whose “greater mass of intelligence” surpassed any nation in Europe, according to de Tocqueville, writing in 1835. (p59) This lofty intelligence directed an aggressively proselytizing zeal that dealt death to all Indians, or sold them into slavery (p62), and informed American Exceptionalism and Manifest Destiny – imperialist ideologies unique to Yankeedom (p63).

Tidewater, essentially Chesapeake Bay and the eastern halves of Virginia and North Carolina, began in Jamestown in 1607, not as the heroic outpost of civilization that “every schoolboy knows,” but as “a hell hole of epic proportions” (p44) and “a corporate-owned military base.” (p45) Composed of gentleman-adventurers and vagrants, they came to find treasure and to conquer. They slaughtered Indians – men, women, and children – and made peace treaties only to serve them poison at the treaty banquet (p46). Most of the immigrants ended up dying of disease and starvation, resorting to cannibalism (p45). Woodard’s demolition of the Pocahontas myth is both hilarious and revealing:

[Captain John] Smith was subjected to the Indians’ adoption ritual – a mock execution (interrupted by the chief’s eleven-year-old daughter, Pocahontas) and theatrical ceremony which, from the Indians’ point of view, made Smith and his people into Powhatan’s vassals. Smith interpreted the situation differently: the child, overwhelmed by his charm, had begged that he be spared. Smith returned to Jamestown and carried on as if nothing had changed, flabbergasting the Indians. (p46)

The colony did not prosper until Pocahontas’ husband, John Rolfe, introduced tobacco from the West Indies. This crop was very labor-intensive, so vagrants and indentured servants from London, Bristol, and Liverpool were imported. Africans did not arrive until 20 of them were brought into Chesapeake Bay by Dutch traders in 1619. However, they worked side-by-side with indentured whites until after the 1670s (p48). Sir William Berkeley was the Royalist governor of the colony when the English civil wars began in the 1640s. He invited hundreds of the “distressed Cavaliers” loyal to the king, offering Virginia as a refuge from Cromwell’s Protectorate. They immediately became the ruling oligarchy. Among them were Richard Lee (Robert E. Lee’s great- great- great-grandfather), John Washington (great- great-grandfather of George Washington), and George Mason (great- great-grandfather of the Founder of the same name) (p51).

The Deep South’s identity was radically different from the other ten, in that its founders were not from Europe, but from the ruling families of Barbados slave plantations. They settled Charleston and eventually all of South Carolina, instituting a caste system that enslaved a much larger black population whose brutal treatment resulted in double the mortality of Virginia slaves (p83). The rulers’ arrogance and extravagance made Charleston “the wealthiest town on the eastern seaboard.” (p85)

These observations should make clear that all of America had slaves, and that there were different varieties of slavery, even throughout the War Between the States period. Edmund Ruffin’s 1860 Slavery and Free Labor illustrates that the Virginia slave’s physical well-being was better than the Irish tenement “free” laborer in New York City. But to say that any slave, no matter how well fed, is inferior to any free man, no matter how impoverished – as we most emphatically do – is to refute historian Ira Berlin’s assertion that Yankeedom was merely a society with slaves, while the South (without distinction, whether Virginia, South Carolina, or elsewhere) was a slave society.

Greater Appalachia, running down the backbone of those mountains from western Virginia to Macon, Georgia, and later, down the Ohio River valley, through Missouri and Arkansas to the Texas Big Bend country, was settled by Irish-Scots immigrants from the Borders between Scotland and England and from Ulster, Ireland whose “ancestors had weathered 800 years of nearly constant warfare.” (p101) To call them “yeoman farmers” seems almost too dignified a term to distinguish them from the slaveholding aristocrats farther east. They lived in happy subsistence in the marvelously fertile back country, relying more on their extended clans and personal violence than on any formal court system for justice, and on whiskey for the primary unit of account in their barter economy.

The Midlands nation owed its founding to a royal charter from Charles II, granted to the “very, very rich” (p94) William Penn in settlement of the king’s debts to him. Buddha-like, Penn devoted his vast wealth into establishing George Fox’s almost fatally pacifist sect in Pennsylvania. This nation would push due west to Nebraska, beginning with the arrival of industrious and politically passive Germans, mainly from the Lower Palatine (midway up the Rhine in western Germany), escaping the Thirty Years’ War (1618-1648).

New Netherland was founded in 1624 as a Dutch enclave in present-day greater New York, until its defeat by the English 40 years later. Because of its mercantile openness to all religions, it remained an enemy of Yankeedom.

Among the five remaining nations (New France in present-day Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, and New Orleans; First Nation around Hudson Bay to Greenland, composed of native Indians there; the Far West, from the Great Plains to the Left Coast; and El Norte from the watershed of the Rio Grande, north from El Paso to Colorado, west from El Paso to Los Angeles to include the northern half of Baja), El Norte is the most interesting to this Texan. Present-day Texas includes bits of four different Woodard nations, the largest being Greater Appalachia. El Norte illustrates Woodard’s emphasis on culture to the exclusion of all other considerations, especially topography. While it is true that Texas was once in the same Mexican state with Chihuahua, that south Texas and the Rio Grande valley are culturally Mexican, and that the notable José María Jesús Carbajal did secede from Mexico to form the Republic of the Rio Grande (lasting the first nine months of 1840), the river demarcates Texas from a much different area of institutional collapse to the immediate south.

What is crucial in Woodard’s account is that these eleven cultures never put aside their regional differences, even during the Colonial period and when framing the Constitution. During the war, their only shared structure was the Continental Congress, which “was essentially an international treaty group” (p141). Over the period between August 1777 and May 1787,

Not a single delegate from either of these blocs [Yankeedom vs Tidewater and the Deep South] ever voted consistently with a colleague from the other. (p142)

British secret agent Paul Wentworth reported to the Crown in 1778 that there was not one America, but three: An Eastern (Yankeedom), a Middle (New Netherland and the Midlands), and a South (Tidewater and the Deep South) (p144). At the Constitutional Convention in 1789, the so-called “Virginia Plan” of a strong central government won out over the decentralized “New Jersey Plan” of the Midlands and New Netherland because the oligarchs of Yankeedom and Tidewater saw their future interest in it. As for the famous compromise of a proportionally elected House and a two-members-per-state Senate, Woodard writes:

The split, oddly enough, was not between large states and small ones, but rather between Yankees and the Deep South. (p147)

The Yankees feared a future population growth to the west in the South. Greater Appalachia had virtually no voice in the convention, having only James Wilson of Pennsylvania as its representative. And was the Bill of Rights adopted as a common assurance against too much central power? Not exactly, writes Woodard. It was taken from the New Netherland nation’s Articles of Capitulation, written as terms of surrender by the Dutch to the English in 1664 (pp147-148) – indeed a kind of “terms of surrender” to yet another new government.

Curiously, after offering an account of the cultural forces that provides such a satisfying reinterpretation of American history, Woodard turns his back on it. He rather oddly and unconvincingly suggests that a First Nation led by ecological experts and women might provide a paradigm going forward (pp319-321). Beyond that, he offers no solutions. After admitting that “the ‘red’ and ‘blue’ nations will continue to wrestle with one another for control over federal policy,” on page 317 he sketches – in this book written a decade before COVID – a more dire possibility, that

leaders will betray their oath to uphold the U.S. Constitution, the primary adhesive holding the union together. In the midst of, say, a deadly pandemic outbreak […] a fearful public might condone the suspension of civil rights […].

After this event, he speculates on the formation of “one or more confederations of like-minded regions.” Then he adds:

If this scenario of crisis and breakup seems far-fetched, consider the fact that, forty years ago, the leaders of the Soviet Union would have thought the same thing […].

Woodard adamantly insists that his distinctions are strictly cultural – not tribal, and oh god help him, no, not racial; and that the Constitution is the most important and most viable common ground that can yet hold together his eleven contending regions. To this we must say granted, the Constitution makes universalist claims; it provides a clear set values that ought to be the shared political culture of every person, regardless of his tribal affiliations – surely the one abstract “society” claim that trumps the many personal “community” claims – surely the one remaining shared value. The Constitution ought to be the document that defines the propositions of what is said to be a “propositional nation.” But currently, it isn’t. It isn’t because it can’t, given the crushing of Madison’s federalism on April 9, 1865. Now, a “consolidated” government asserts supremacy not only over state sovereignties, but over the affairs of every individual, directly and without intermediation. There cannot be a national consensus when the debate is not over the methods of realizing a few shared national goals, but is instead over the radically different goals themselves, sweepingly imposed on every region and person in a winner-takes-all, zero-sum cage fight. The Constitution that once instituted Madison’s federalism is now a “living document” interpreted by a completely politicized judiciary whose final word is the tool of the triumphant faction of the season.

And yet, society cannot exist without some set of shared values. For the United States, what is it? Increasingly, it is the unanimity regarding race. The universally shared value that racism is a bad thing forms the ersatz unifying proposition for all Americans. Not one American advocates racism. Politicos who came to power playing the race card repeat the mantra: “We’ve come a long way on race, but we’ve got a long way to go.” The truth is that America, over the span of a single generation, eradicated in the heart of every last one of its citizens what was for some a deeply held personal bias. Uttering a racial epithet in anger on the playing field or at work no longer reflects any such abiding belief. Racism does not exist in America.

And yet the mantra, the indispensible political crutch, the sole remaining unifying proposition, must drone on. Since no one can be found to overtly champion racism, a “structural” racism must be found so that a united America can stamp it out. And when it is not found, ever more frenzied attempts must be made to find it, for it must exist – for how else are our goals for social harmony so persistently thwarted? It must be because we have defined race too narrowly: We must broaden it to include groups that share some grievance just as debilitating as racial discrimination. Ever more groups must be included; ever more theories must be hatched by the professors of ethnic studies; ever more ruthless fines and punishments must be meted out to eradicate this oh-so-elusive menace; public sacrifices must be performed by the media priests to keep this evil spirit at bay. The careless spoken word or social media comment must be exposed even at the cost of someone’s livelihood and personal humiliation, despite his abject profession of allegiance to the one remaining shared value among Americans. And clearly the blunt, unanswerable charge of offending this value can serve only to further inflame hatred and division, which multiplies even more charges of racism. Woodard provides the historical foundations of the nations that might be reconstituted out of the inevitable break-up of the American Leviathan. He is a historian, not a secessionist, not a political scientist. But he has provided an invaluable description of the artificial Union that must be prevented from destroying the regional nations that are the expression of what lies nearest to the heart of every true patriot