This essay is from Brion McClanahan and Clyde Wilson’s Forgotten Conservatives in American History (Pelican, 2012).

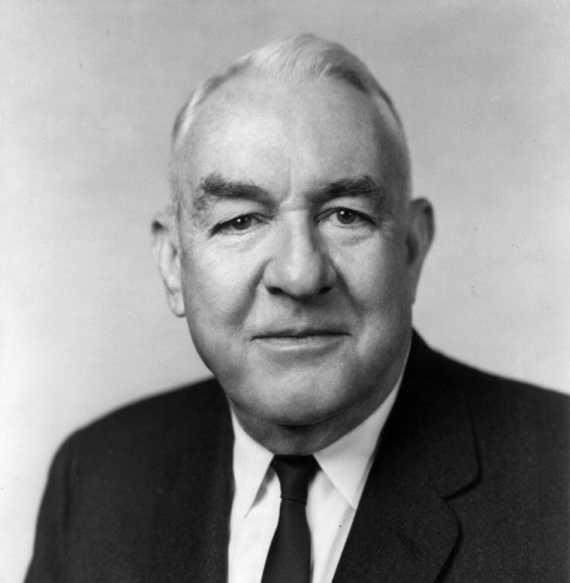

In 1973, Senator Sam Ervin of North Carolina was perhaps the most respected and popular member of the United States Congress. His role in the televised Watergate hearings as chairman of the Senate Select Committee led one member of Congress to remark that he was “the most nonpartisan Democrat in the Senate.” T-shirts were made in his honor; everyone had a favorite “Senator Sam” story; he starred on an album entitled “Senator Sam at Home;” his face was pressed on Newsweek and Time; fan clubs appeared; and it became “chic” to have a Southern accent and spin down-home tales of life in the rural South. Millions adored him. But Ervin didn’t buy into this heroic public image. He was seventy-seven and had already decided he would retire in 1975. He maintained a listed phone number at his residence in Washington D.C. for most of his time in the Senate (he only changed it after several unusual phone calls during the Watergate hearings led his wife to demand a new unlisted number), and he called himself a simple “country lawyer.” He lived in the same house in Morganton, North Carolina most of his life (across the street from his birth home), greeted neighbors and constituents himself at the front door, and graciously accepted produce on his porch from local farmers. He would often remark that his wife of over fifty years kept him grounded. Senator Sam was truly one of the people.

Yet, Ervin’s disarming smile, humorous stories, and folksy persona masked the depth of his intellect. This “country lawyer” took some of the most famous members of the Washington establishment to task for their flagrant violations of the Constitution. His autobiography, titled Preserving the Constitution, is a testament to the defining cause of his career, saving the Constitution of the Founders from the designs of “legislative and judicial activists…bent on remaking America in the image of their own thinking.” He was rarely successful, but Ervin had a unique perspective on his many defeats. He believed Southerners had a “certain peculiarity due to the fact that all of their greatest heroes were men who failed…men like Robert E. Lee, Stonewall Jackson and J.E.B. Stewart and those who followed them. These men failed in their objective, and the fact that they failed in their objective I think teaches some of us that the truth that’s embodied in the little poem by Edwin Markham….Defeat may serve as well as victory to shake the soul and let the glory out, and I think we need more of that spirit in this country that success is not the important thing, it’s what you do and how you try to win success….If you do not win success and you fight for your cause with valor, the defeat which you may suffer will shake the soul and let the glory out as well as victory will.”

With such a colorful and important past, why has Ervin been forgotten? After scolding Richard Nixon for his abuse of executive powers during the Watergate hearings, Ervin was the darling of the progressive Left in 1973. At the same time, the finicky (and uninformed) Left often derided his supposed “inconsistency” with their worldview. The same Sam Ervin who relentlessly sought to check executive abuse in 1973 had stared down then United States Attorney General and Leftist hero Robert F. Kennedy during congressional hearings on civil rights legislation, had opposed the Voting Rights Act of 1965 and the Civil Rights Act of 1964, and called Kennedy and other Northern men like him bigots for their apparent anti-Southern bias. How could such a constitutional scholar, they thought, support what were to them such unconstitutional positions?

It is the label “inconsistency” that has survived and why Ervin has descended into the depths of obscurity. He has been described as the intellectual mastermind of the “soft” Southern approach to blocking civil rights legislation. Under this charge, defending the Constitution was little more than a code-word for racism and “hate speech.” Even his most recent biographer, Karl Campbell, claimed that Ervin’s “preoccupation with maintaining the racial status quo contributed to an overly limited view of government power.” According to Campbell, Ervin, in typical Southern fashion, favored the Constitution in the same way that Southern slaveholders clung to “virulent federalism” at the “Constitutional Convention in 1787” in order to protect “black chattel slavery, just as the strict constructionism and states’ rights rhetoric of later generations of southerners served the cause of white supremacy.” Campbell called this a “critical flaw in Ervin’s constitutional philosophy.” While Campbell applauded Ervin’s approach to civil liberties and executive power, he also argued Ervin should have recognized that strong central authority is “sometimes necessary.”

Not only is Campbell’s characterization of Southern federalism in the early republic wrong, but his assessment of Ervin’s cogency in defending the Constitution as some deep seeded hatred for black Americans belies reality. If Ervin had simply used the Constitution to his advantage during the civil rights era and then simply thrown it aside after that time, then Campbell and other critics of Ervin’s public career would be correct; he would have been inconsistent. But Ervin’s record is clear. He consistently and faithfully adhered to his oath to “support and defend the Constitution of the United States….” Whether he was waging war against Richard Nixon, defending civil liberties in the 1960s, or pointing out the legal and constitutional flaws of civil rights legislation, Ervin was attempting to save the Constitution of the Founders. The struggle to preserve the Constitution was a struggle to uphold the founding principles of the United States. He was a Jeffersonian, a ‘76er, a States’ rights Whig well versed in the American political tradition of decentralization. That is his legacy.

Sam J. Ervin, Jr. was born in Morganton, North Carolina in 1896 as one of ten children to Sam J. Ervin, Sr., a well-respected trial lawyer in and around Burke County, and Laura Powe Ervin. Both the Ervins and Powes counted a number of ancestors who fought for American Independence and several members of both families, including Ervin’s paternal grandfather, served in the Confederate army during the War Between the States. Sam Ervin, Sr. passed to his son a reverence for the Constitution as “the guardian of our liberties” and a disdain for “governmental tyranny and religious intolerance.” He was reared on tales of Southern valor, and respected his father for carrying “his own sovereignty under his own hat,” meaning “he adopted and advocated what he believed to be true, regardless of whether it coincided with views popularly held.”

Ervin was also the consummate Southern gentleman and learned from his mother the values that molded his professional career: honesty, integrity, hard work, politeness, and most importantly, a reverence for tradition and place. He once wrote that he was “born of Burke County’s bone and flesh of Burke County’s flesh. Hence, outsiders may think I am biased in its favor. Be that as it may, I am satisfied that when the Good Lord restores the Garden of Eden to earth, He will center it in Burke County because He will have so few changes to make to achieve perfect creation.”

Ervin enrolled at the University of North Carolina in 1913 and was graduated in 1917 while serving in Europe during World War I. The classical education he received influenced his love of literature and respect for history. Ervin counted the history professors at North Carolina as his greatest influences. History, they taught him, “is the torch of truth, and as such is forever illuminated across the centuries the laws of right and wrong,” and from J.G. de Roulhac Hamilton, the dean of North Carolina history, Ervin learned that “one cannot understand the institutions of today unless he understands the events of yesterday which brought them into being.” Of particular and lasting importance was a speech given by University President Edward Kidder Graham during chapel hour one morning where he insisted that the young men remember that the Magna Charta, the English Petition of Right, the English Bill of Rights, the Declaration of Independence, and the United States Constitution were “the great documents of history. These are living documents. Cut them, and they will bleed with the blood of those who fashioned them and those who have nurtured them though the succeeding generations.”

Ervin left the University of North Carolina and was commissioned a second lieutenant in the United States Army in 1917. He was part of the first expeditionary forces to land in France and participated in the Battle of Soissons. He was wounded twice (once at Cantigny before Soissons) and awarded the Distinguished Service Cross for his leadership in capturing a German machine gun nest during the action at Soissons. He was honorably discharged in 1919 and returned to Morganton to practice law. Most in North Carolina did not know that Ervin had been reduced to the rank of private early in the war for abandoning his command. This was only revealed in his autobiography shortly before his death in 1985. Regardless, Ervin bore the scars of Soissons for the rest of his life and his gallant actions saved the lives of many men. Shortly before the battle of Soissons, Ervin recounted that the company chaplain, a Catholic Priest, had said, “Before tomorrow’s sun sets, many of you I see standing before me in the vigor of youth will have made the supreme sacrifice on the battlefield for the America all of us love.” Ervin never forgot those words, and whether it was at Soissons, North Carolina, or Washington D.C., he continued to fight for the America he loved and the founding principles of the United States for the remainder of his life.

After returning to Morganton, Ervin was admitted to the North Carolina Bar in 1919 and enrolled in Harvard Law School the same year. He was the only person in the history of the school to complete his work in reverse order, taking the third year classes first, then the second, until he finished his final examinations in 1922. He practiced law at his family firm, Ervin and Ervin, until 1937, and served in a number of elected positions in North Carolina, most importantly as a member of the North Carolina General Assembly in 1923, 1925, and 1931. While in the State legislature, Ervin displayed the same principled defense of civil liberty that would mark his career in the United States Senate. He opposed attempts to prohibit the instruction of evolution in North Carolina public schools—Ervin considered freedom of religion the most essential liberty—and fought for increased funding for black schools in Morganton and elsewhere. He was appointed Special Superior Court Judge in 1937 and held that appointment until 1943.

He was elected to the United States House of Representatives in 1946 and served for one year. This introduced Ervin to federal politics, but he was happy in North Carolina and declined to seek reelection. Yet, his time in the House impressed upon him that “the framers of the Constitution of the United States and North Carolina gave us a government of laws rather than a government of men. Fidelity to the government of laws is essential if good government, the reign of law, and liberty are to endure in our land.” He was appointed to the North Carolina Supreme Court in 1948 and served until 1954 when he was sent to the United States Senate. Ervin summed up his career in the North Carolina Supreme Court in one of his opinions: “Ministers of the law ought not to permit zeal for its enforcement to cause them to transgress its precepts. They should remember that where law ends, tyranny begins.” This bit of legal philosophy exemplified his political career in Washington and would make him at one time the most famous man in Congress.

Ervin was a statesman, a man who stood on principles rather than the ebb and flow of popular opinion. He was regarded as an independent Democrat and often voted with Republicans when he believed “that their position right.” No one could corral him, and he infuriated opponents by refusing to acknowledge their attacks. This made him popular and powerful in Washington. He believed in the traditional role of a United States Senator, meaning he represented the people of the State of North Carolina in Washington, rather than the amorphous mass of the American people. “The Founding Fathers,” he said, “accepted as verity this aphorism of the English Philosopher Thomas Hobbes: ‘Freedom is political power divided into small fragments.’” As a consequence, Ervin argued that the States and local government were an essential component of the American political system.

Local process of law are an essential part of good government because the national government cannot be as closely in contact with those who are governed as can the local authorities in the States and their several subdivisions. Local government is the only breakwater against the ever-pounding surf of the national government’s demand for conformity to its delegates, a demand that threatens to submerge the individual and destroy the only kind of society in which personality can exist.

His indictment of the centralization of power in Washington spared no one. He contended judicial activism on the part of the Supreme Court “expanded the powers of the federal government and their own powers and diminished the powers of the States.” Centralization made it possible for corrupt lobbyists to force congress to do their bidding, for it was “easier and more productive to deal with one legislative body, Congress, then to deal with 50 state legislatures.” The executive branch “usurped the power of Congress to legislate by executive orders, and Congress sometimes abdicated its power to legislate to the Presidency by enacting vague statutes that delegated to the enforcing department or agency the authority to make implementing regulations.” The end result was the destruction of “good government…the freedom of individuals [and] fiscal sanity.”

Corruption was one of the primary fears of the Jeffersonians and why they preferred diffusion of power. Ervin lamented that the corruption in Washington during his time was “aided and abetted by the public officials of many of the States who accepted dictation from federal departments and agencies in return for grants and loans of federal moneys.” The end result was debt and fiscal irresponsibility. “Congress spurned both honest and intelligent choices…until it overwhelmed our nation with ruinous inflation and the most enormous national debt of any nation on earth.” Ervin contended that excessive spending was “dishonest because it creates inflation, and inflation robs the past of its savings, the present of its economic power, and the future of its hopes as well as its unearned income.” And fiscal irresponsibility did not stop at American borders. To Ervin, the United States had become “an international Santa Claus, who scatters untold billions of dollars of the patrimony of our people among multitudes of foreign nations, some needy and some otherwise, in the pious hope that America can thereby purchase friends and peace in the international world, and induce some foreign nations to reform their internal affairs in ways pleasing to the dispensers of our largess.” This was Hamiltonianism run amok. Patronage and dollars were, and still are, used to buy votes and centralize authority. This made Ervin’s independency refreshing.

There were two issues that defined Sam Ervin’s senatorial career: his opposition to federal civil rights legislation and his political war with Richard Nixon. In both cases, Ervin displayed a principled defense of the Constitution and the “federated Republic” of the Founders. His opposition to the Civil Rights movement has become a thorny issue in recent years and has made Ervin, along with other members of the “Southern bloc” of the United States Senate pariahs in American history. They have been characterized as race baiters, thugs, and old-fashioned advocates of a social order contradictory to the founding principles of the United States. In regard to men like Theodore Bilbo of Mississippi, the first two descriptions are true—Erin distanced himself from such rhetoric—but Ervin took issue with the last statement, not out of racial hatred, but because he argued civil rights legislation destroyed the Union of the Founders. His positions were Jeffersonian and displayed a legal brilliance virtually unsurpassed by modern constitutional scholars.

Biographer Karl Campbell called Ervin’s tactics “insidious.” This is more a reflection on Campbell’s biases than Ervin’s constitutional philosophy. Ervin publicly insisted he harbored no ill will toward black Americans. He had, in fact, championed better treatment for North Carolina’s black population on several occasions while serving as a member of the North Carolina legislature, and nary could a private statement be found linking him to the racist rhetoric that is often attached to opponents of civil rights. Biographer Paul Clancy summed up his opposition this way:

Ervin fought civil rights legislation, in part, because he had to…He saw the need for correcting the injustice of job discrimination, ghetto housing, and segregated schools. But passing federal legislation, setting up a federal bureaucracy to administer it, and aiming it—especially aiming it—at the South put Ervin in a corner. Like Robert E. Lee, who did not agree with everything that was going on in the South, Ervin felt it was his duty to fight. Like Lee, Ervin believed that “duty” was the most sublime word in the language.

Ervin anticipated the type of attacks that would be used against him both during and after his time in Congress. The most common was the claim of inconsistency, a charge that virtually every article or book written about Ervin contains. In his autobiography, he succinctly defended his work against civil rights legislation in the hope of disarming these attacks:

Many persons of undoubted sincerity deem all civil rights proposals as sacrosanct and all persons who oppose them to be racial bigots. They charge me with inconsistency in advocating equal civil liberties for all Americans and opposing special civil rights for Americans of minority races. My positions in these respects are not inconsistent. They are completely harmonious. Equal civil liberties for all and special civil rights for some are incompatible in concept and in operation….There is an unbridgeable gap between civil liberties and civil rights. Civil liberties belong to Americans of all races, classes, and conditions. Civil rights are special privileges enacted by Congress, or created by executive regulations, or manufactured by activist Supreme Court Justices for the supposed benefit of members of minority races on the basis of their race.

What many Americans viewed as moral justice Ervin saw as an affront to constitutional government and a slippery slope to tyranny and the destruction of the Union of the Founders. As a member of the Senate Judiciary Subcommittee on Constitutional Rights, Ervin was in the unique position to filet any civil rights bill that came before the Senate. Between 1957 and 1972, there were dozens. Ervin labeled each one “unconstitutional…tyrannical, or unnecessary,” and while he could not kill most, he succeeded in watering down or delaying most of them. In every case, the Constitution was his shield and history his sword.

Ervin first went on the offensive in 1957. President Dwight Eisenhower insisted on a civil rights legislation package and put pressure on Congress to act. Ervin called the proposed 1957 civil rights act “utterly repugnant to the American constitutional and legal systems.” In a long indictment of the bill, Ervin explained that the American tradition was built on legal safeguards and that the founding generation, both during the American War for Independence and afterward, steadfastly determined to ensure that Americans would never face the same type of tyrannical government they suffered under in the 1760s and 1770s. In Ervin’s mind, the most egregious affront to civil liberty was the denial of trial by jury. The 1957 civil rights bill removed that essential protection from the American people.

They [the Founders] knew that tranquility was not to be always anticipated in a republic; that strife would rise between classes and sections, and even civil war might come; and that in such time judges themselves might not be safely trusted in criminal cases, especially in prosecutions for political offenses, where the whole power of the executive is arrayed against the accused party. They knew that what was done in the past might be attempted in the future, and that troublous times would arise, when rulers and people would become restive under restraint, and seek by sharp and decisive methods to accomplish ends deemed just and proper and that the principles of constitutional liberty would be in peril, unless established by irrepealable law.

Ultimately, Ervin contended that every civil rights bill that crossed his desk violated the principles of American government, be it the Civil Rights Act of 1964, the Voting Rights Act of 1965, or the Equal Employment Opportunities Act of 1972. By creating federal departments and agencies with the power to act as “law-maker, prosecutor, jury, and judge in the same office or agency,” these laws destroyed the separation of legislative, executive, and judicial powers the Founders considered essential to good government. Not only were these regulatory agencies unconstitutional, they were “inimical to due process, and fair play.” And with the Supreme Court acting in concert with the legislative branch in declaring these laws constitutional, Ervin believed there was no hope for liberty or free government in America. In 1963, Ervin wrote that “The proponents of current civil rights legislation, many of them undoubted men of good will, would, in an attempt to meet a genuine problem concerning the inflamed nature between the races in this country, trounce upon an even more pressing need—the need to preserve limited, constitutional government in an age of mass bureaucracy and centralization.”

Late in life, Ervin lamented that “The most serious threat to good government and freedom in American is not posed by evil-minded men and women. It is posed by legislative and judicial activists and other sincere persons of the best intentions, who are bent on remaking America in the image of their own thinking. They lack faith in the capacity of the people to be the masters of their own fates, and the captains of their own souls, and insist that government assume the task of controlling their thoughts and managing their lives.” Many Americans, particularly Northerners, considered Ervin a paranoid, delusional, bigoted, lunatic in the early 1960s, but by the Richard Nixon administration, many of his dire prophesies came true, and it was Ervin, not the champions of unbridled central authority, who was proven correct.

Ervin believed executive abuse had been a problem since he first arrived in the United States Senate. He had battled with the Eisenhower administration—Eisenhower in fact coined the term “executive privilege”—over withholding information from the Congress. Every occupant of the White House from that point forward expanded on the fabricated “privilege,” but Richard Nixon used the tactic better than anyone before him. Ervin feared the effect Nixon was having on free government. His administration was infamous for invoking “executive privilege” to enhance the power of the executive, mostly at the expense of Congress and the States. Ervin lamented Congress was partly responsible for the problem. “In all candor, we in the legislative branch must confess that the shifting of power to the executive has resulted from our failure to assert our constitutional powers.” The end result in his mind would be “a government of men, not of laws.” Here again was the corruption that Ervin dreaded.

Nixon was not the first to appoint “czars” to circumvent the legislative process and arrogate power to the executive, but to that time he was perhaps the most flagrant in their use. Additionally, Nixon supported trouncing civil liberties in the name of “national security” and withheld critical information on the Vietnam War under the guise of “executive privilege.” At every turn, Ervin attempted to block this spiraling trend toward centralization. Though reluctant to serve as chairman of the Watergate hearings, Ervin eventually viewed this role as the opportunity to expose the “imperial presidency” and crush usurpation of power by the executive branch. He admitted that finding the truth in the Watergate conspiracy represented a “herculean task,” but he was up for the challenge and viewed it as his duty to act.

In his opening statement during the Watergate hearings, Ervin said that “The Founding Fathers, having participated in the struggle against arbitrary power, comprehended some eternal truths respecting men and government. They knew that those who are entrusted with power are susceptible to the disease of tyrants which George Washington rightly described as ‘love of power and the proneness to abuse it.’ For that reason, they realized that the power of public officers should be defined by laws which they, as well as the people, are obligated to obey….”

His Jeffersonian view of executive authority led him to conclude that, “In my judgment the President’s power under the Constitution in respect to all congressional acts of which he disapproves is limited to vetoing them, and allowing Congress to nullify his veto by a two-thirds majority in each House if it so desires.” As he said more succinctly, “Divine right went out with the American Revolution.”

Through Ervin’s crafty use of wit, humor, charm, and a penchant for knowing what to say and when to say it, it became clear to the American public that Nixon, and essentially every American president, had become an elected king. Ervin had finally removed the shroud of deception, something he had been attempting to do for almost twenty years. It was bitter sweet justice. Nixon buckled and later resigned due in large part to Ervin’s brilliant performance during the Watergate investigations, but by the late 70s it seemed that Americans forgot or failed to heed the lessons of 1973.

Nixon’s enforcers tried to tarnish both Ervin and the committee hearings by labeling them as pure partisanship and a witch hunt to destroy a Republican president. To Ervin they were not—he was searching for “truth and honor”—but to many Democrats, the label stuck. As long as “their guy” was in office, Democrats cared little for executive restraint, civil liberties, or the Constitution. Republicans were no different. Ervin, however, was a dying breed of American statesman, one that has rarely darkened the halls of Congress in the modern era. He would vote his conscience, even if it meant he was the lone voice of opposition, as he sometimes was. Ervin proudly held up his congressional voting record as a model of consistency. When he retired in January 1975, everyone recognized Senator Sam as the most principled man in Congress, if not Washington D.C. There has been no-one like him since.

Biographer Karl Campbell labeled him a conservative obstructionist bent on preserving the “southern status quo,” most importantly the “racism, civility, and paternalism” of the South. To men like Campbell, there has to be a deeper, more sinister motivation to States’ rights, strict construction, or a principled defense of republicanism than simply “defending the Constitution.”

Certainly, culture shapes many decisions in life, and Burke County was in Ervin’s blood and bones, but to suggest that the Constitution was nothing more than a utilitarian means of enforcing Ervin’s world-view, as Campbell does, is to sell short Ervin and his principled defense of American conservatism. Ervin considered the Constitution sacrosanct because he considered the American tradition and the principles of ’76 sacrosanct. As Ervin said in an interview with William F. Buckley in 1978, “I think that if you have to violate your constitution in order to save your country—you have to lose your constitution—I think your country’s lost anyway.” It had been lost since 1861, but at least with men like Ervin around, a little bit of the spirit of ’76 remained in the federal capital. Not only was Ervin the last constitutionalist, he was the last Democrat in the Jeffersonian tradition.