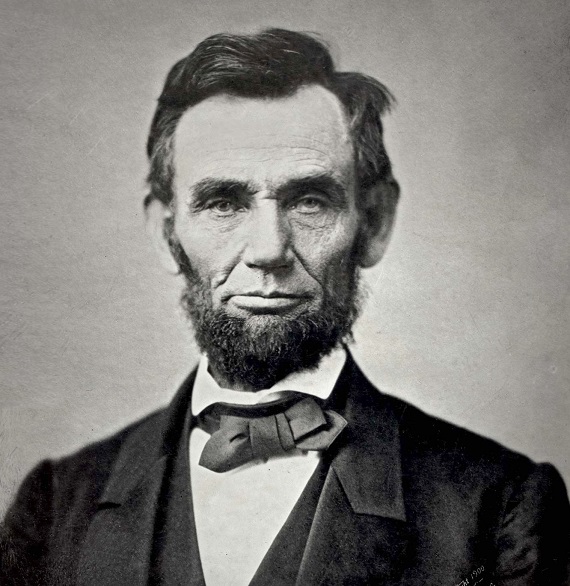

On March 7, 1862, Lincoln sent to congress and congress passed a joint resolution offering pecuniary aid to any State that would initiate gradual emancipation. However, no funding had been passed, only a declaration of intent. The offer fell on deaf ears in all the slave States, including those still in the Union.

This prompted Lincoln to call a meeting on July 12, 1862 of the Representatives and Senators of the border slave States that had not joined the “rebellion.” What was Lincoln up to? Was he so concerned about the welfare of the slaves that he was willing to expend an enormous amount of federal revenue (at a time when the budget was severely strained by war) and diplomacy to secure their freedom? Here is the reason he gave to the border State representatives:

“…if you all had voted for the resolution in the gradual emancipation message of last March, the war would now be substantially ended – And the plan therein proposed is yet one of the most potent, and swift means of ending it. Let the states which are in rebellion see, definitely and certainly, that, in no event, will the states you represent ever join their proposed Confederacy, and they can not, much longer maintain the contest. But you can not divest them of their hope to ultimately have you with them so long as you show a determination to perpetuate the institution within your own states… – You and I know what the lever of their power is – Break that lever before their faces, and they can shake you no more forever” (Emphasis added)

As in his later Emancipation Proclamation, Lincoln hoped an offer of compensated emancipation would end the war. It was not a moral concern for the slaves; it was a war strategy. He believed if the border States ended slavery, it would convince the seceded Confederate States that the border States would never join their side, and therefore the CSA would see the futility of its cause and end its “rebellion.“ Lincoln believed that slavery was “the lever of their (the CSA’s) power,” and that power would be broken with a loss of any hope of the border States as allies. The CSA’s secession, Lincoln believed, was all about protecting slavery.

Meanwhile, his plan for the slaves when freed had not changed, they were to be deported to South America to rid the country of blacks:

“Room in South America for colonization, can be obtained cheaply, and in abundance; and when numbers shall be large enough to be company and encouragement for one another, the freed people will not be so reluctant to go.”

The border States soundly rejected the plan 20 – 8. Why? Were they so enamored with slavery they were unwilling to give it up? The reasons for those voting against the proposal were listed in a letter to Lincoln on July 14, 1862. None of them were a desire to “perpetuate the institution.” First, they were concerned that such a radical social change was rushed through Congress without time for debate. Second, they felt the Federal gov’t was interfering in what should be a State’s Rights issue. Third, they questioned the Constitutionality of the resolution ever being made law in order to appropriate the funds. Fourth, they had financial concerns, “If we pause but for a moment to think of the debt its acceptance would have entailed, we are appalled by its magnitude…” Fifth, they were concerned about the equal application of the Constitutional rights of the States, and against unequal financial sacrifice being required of them that was not being required of others Union loyal State:

“It is enough for our purpose to know that it is a right; and so knowing, we did not see why we should now be expected to yield it… we did not see why sacrifices should be expected of us, from which others, no more loyal, were exempt.”

Finally, in a clarifying statement significant to the why of secession for the seceded States, these border State representatives took Lincoln to task as to why his plan would not end the war. They did not agree that slavery was the “lever of their power” around which the Southern States rallied secession! They pointed out that “their lever” was Northern infidelity to the Constitution and the desire to use the central government for sectional advantage against the South that was “the lever of power” by which the Southern States rallied around secession and war:

“In both houses of Congress we have heard doctrines announced subversive of the principles of the Constitution and seen measure after measure founded in substance on these doctrines proposed and carried through which can have no other effect than to distract and divide all loyal men and to exasperate and drive still further from us and their duty the people of the rebellious states… To these causes Mr. President, and not to our omission to vote for the resolution recommended by you, we solemnly believe, we are to attribute the terrible earnestness of those in arms against the government and the continuance of the war. Nor do we, permit us to say Mr President with all respect for you, agree that the institution of slavery is “the lever of their power” but we are of the opinion that “the lever of their power” is the apprehension that the powers of a common government created for common and equal protection to the interests of all will be wielded against the institutions of the Southern States.” (Emphasis added)

According to this letter, written in July 1862 by border States congressmen STILL LOYAL TO THE UNION, the rebellious States seceded and fought not for slavery, but for INDEPENDENCE from a section of the country unfaithful to the compact that provided “for common and equal protection to the interests of all.”

So much for the modern myth that Southern secession was all about “perpetuating slavery.” These 1862 border States representatives were certainly in a position to know what really motivated secession in the slave States, and they set the record straight for Lincoln. In so doing, they set the record straight for a modern academia that claims “States sovereignty” and “Constitutional violations,” as reasons for secession, were mere post war fabrications of a “Lost Cause” school of thought.

- “Message from Border State Congressmen to Abraham Lincoln, July 14, 1862.” Abraham Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress.

- Abraham Lincoln Papers The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, (New Brunswick, N.J.,1953–55), vol. 5, pp. 317–19.

Mr. O’Barr,

Thank you, thank you, for your diligence in study, love of the truth and the south and her heritage, I would that all men would have such strength of mind and character. That the current administration would admit that they are wrong to perpetuate their contiued “WAR” against the south and her children; But alas, goverments are made of men and men are corrupt.

May we all one day be free from corruption and enjoy true liberty.

Respectfully,

R. E. Lee “Marse” Wolfe

SCV and fellow Tennessean

Excellent work.

The Corwin Amendment seconds your motion.

Very true!

However, the Corbin Amendment occurred prior to even this proposed action, back in 1861!