The recent apoplexy over White House Chief-of-Staff John Kelly’s comments about Robert E. Lee and the Civil War have revealed on ongoing problem in the thinking of many Americans when it comes to history and politics in general – the inability to see any issue or event in anything but the most oversimplified terms. In the particular context of the criticism of General Kelly’s comments on the Civil War, the South as a region and the Southerners as individuals could not possibly have had any other motivation to fight than the protection of slavery (in the eyes of the media). For example, witness Paul Begala’s tweet made in response to Kelly’s comments:

“The Civil War was fought over slavery

The Civil War was fought over slavery

The Civil War was fought over slavery.

This will be on the test.”

Unfortunately, history does not ordinarily give us such neat little packages of information to digest, memorize, and repeat like a mantra, and the history of the Civil War is not an exception. In order to understand history in general (and the Civil War in particular) one must first read extensively, and then over time develop the ability to understand and appreciate historical nuance, i.e. the subtleties and fine distinctions commonly found in historical events.

Part of America’s failure to understand historical nuance is related to our culture’s aversion to reading anything longer than a tweet, such as Mr. Begala’s. If an idea cannot be encapsulated in 140 characters, the chances of it being read are greatly reduced. When I met Dr. Gary Gallagher at Gettysburg several summers ago, he said something that I have never forgotten. He said that “to not read is very liberating.” He went on to explain that one can just toss out opinions that are not tethered to facts and feel as if they have contributed a great deal to the conversation, and that their opinion is just as good as anyone else’s. But to be able to appreciate historical nuance as it relates to the Civil War, this will just not do. A good deal of both reading and reflection is necessary to have an informed opinion. Reading tweets or echoing talking points is insufficient.

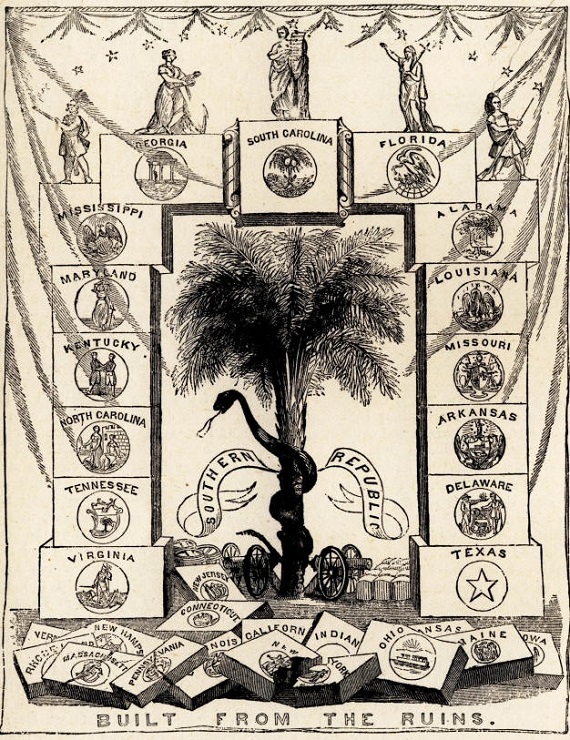

Let me give an example. A commonly heard argument that supposedly proves beyond a shadow of a doubt that the South went to war solely to protect slavery is that South Carolina’s Declaration of Secession mentions slavery a number of times as a cause for secession. Now it is true that slavery is mentioned a number of times in the Declaration. But why one particular state seceded is not necessarily the same reason why another state seceded. While South Carolina’s reasons largely had to do with what they perceived as Constitutional violations in regard to slavery, Virginia’s Ordinance of Secession only mentions slavery once, and that to describe the other seceding states as “slaveholding states.” Indeed, Virginia initially voted not to secede – it wasn’t until Lincoln issued a call for 75,000 to invade South Carolina that she changed her mind. Her secession was a reaction to Lincoln’s response to South Carolina. So we see that different states had different reasons for seceding. They did not form one homogenous whole, and their individual decisions to secede cannot be simplified as such.

But there is another nuance at work here, and it has to do with an assumption made by the South’s critics that the question “why did the South secede?” is equivalent to the question “why did the South go to war?” It seems to me that these are not the same question. General Kelly was criticized for saying that “the lack of an ability to compromise led to the Civil War.” It is puzzling that he was criticized on this point as many compromises between Northern and Southern interests had been reached in the 19th century that staved off a possible earlier war. And it does not take an exceptional mind to imagine other possible compromises that might have achieved the same end in 1861. What if Lincoln had followed the advice of his cabinet and not sent a ship carrying military supplies into Charleston harbor en route to Fort Sumter? What if he had agreed to meet with representatives of South Carolina, who were eager to negotiate a peaceful and compensated surrender of Fort Sumter? War may have been avoided in both cases. But of course this did not happen. South Carolina felt forced into repelling the invasion of its waters. This is an important point as it brings us back to our main point: the reasons why South Carolina seceded (over Constitutional principles related to slavery) and why she went to war (Lincoln’s naval invasion) are not necessarily the same. There could have been secession without war.

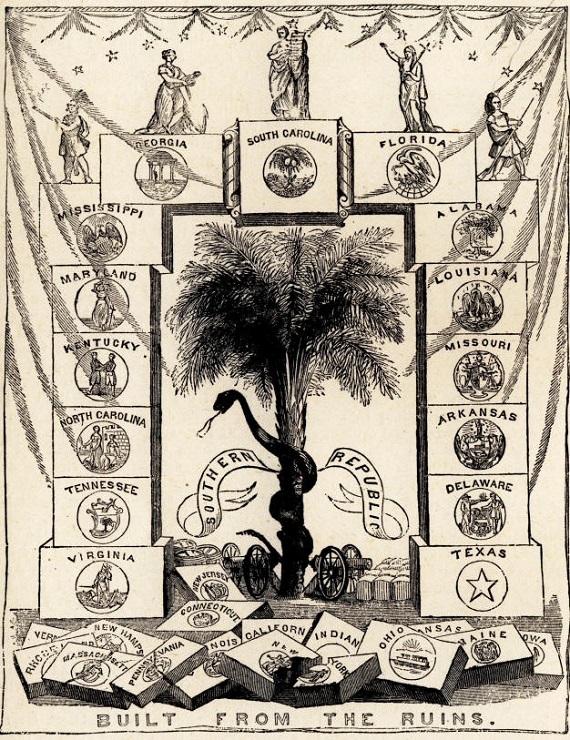

If we move forward in time from early 1861 to the beginning of the war we see yet another layer of historical nuance, which has to do with the motivation of a state to fight a war compared to the motivation of an individual soldier to fight. Again, these are not necessarily the same, and the failure to recognize this leads one to the oversimplified explanations of the Civil War that puts the South and southerners in the worst possible light. Even if the case could be made that every Confederate state went to war for the sole purpose of protecting slavery, that would be a political decision made by representatives of the various states. But it (protecting slavery) would not necessarily be the reason why a Southern boy or man decided to go to war. For one thing, some did not even have a choice – 82,000 men were conscripted to serve. For the vast majority who were volunteers, a myriad of reasons have been found as motivation for their enlistments. But according to novelist and historian Shelby Foote, who spent over two decades researching the Civil War while writing his epic three-volume series of the same name, very few soldiers were motivated to fight on account of slavery. In a 1994 interview he stated that “no soldier on either side gave a damn about the slaves. They were fighting for other reasons entirely in their minds. Southerners thought they were fighting a second American Revolution. Northerners thought they were fighting to hold the union together, and that held true throughout the whole war.” Based on historian James McPherson’s book For Cause and Comrades: Why Men Fought in the Civil War, one could come to similar conclusions. After reading over 25,000 letters and 250 diaries from soldiers on both sides, McPherson found that only 20% of the Confederate soldiers mentioned slavery at all. And this is despite the fact that McPherson’s sources over-represented men from slaveholding families, who were nearly three times more likely to mention slavery as opposed to men from non-slaveholding families. In other words, had a more representative supply of letters and diaries been available for men from non-slaveholding families, the number of soldiers mentioning slavery would have been much less than 20%.

When these historical nuances are taken into account, a much more complicated picture of the relationship between the Civil War and slavery emerges than the simplified version that is so often foisted on the public. To ignore all of this may be comforting to those dedicated to painting the darkest picture possible of the South and the men who fought for her, but ignorance has always been bliss. To find the truth takes a lot of time, work, laying aside of one’s assumptions, and willingness to go wherever the facts may lead. It doesn’t mean that slavery was not a factor at all in the Civil War, nor that racist attitudes were absent in the South. I don’t know of anyone who is arguing that, including John Kelly. But as the General stated, “men and women of good faith on both sides made their stand where their conscience had them make their stand.” People of the South were motivated to act based on many beliefs, not the least of which was the duty of protecting their families and homes while imperiling their own lives. To belittle these heroic people’s actions in order to score a political hit on a member of a disliked President’s staff is a dishonorable thing to do.