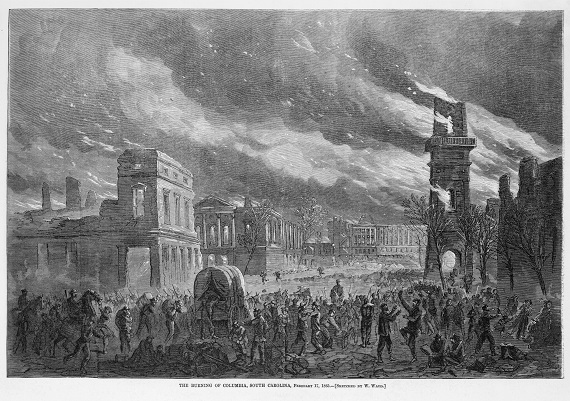

There is nothing new under the sun, but there are things which have lain undiscovered, forgotten, or neglected, and these can be brought to light. In my new book South Carolina in 1865, I have collected unpublished, obscure, and neglected records which document events and conditions in the Palmetto State during the last year of the war. The most cataclysmic event of 1865 was of course General Sherman’s “march” through the South Carolina, climaxed by the burning of the capital city of Columbia, but during the winter of that year even many parts of the state which had not been visited by Sherman’s destructive army suffered tremendously.

One of the documents that motivated this book was a letter written by Josephine LeConte, who was the wife of John LeConte, a professor of physics at South Carolina College (now the University of South Carolina). John LeConte and his brother Joseph LeConte were distinguished scholars and scientists, and a few years after the war, unable to tolerate the carpetbagger government in South Carolina, they moved to California, where they became two of the first faculty members of the University of California at Berkeley. Their papers are housed at the Bancroft Library at UC Berkeley, and in those papers are letters written during the war, most of which have never been published in full.

In a letter that Josephine wrote to her son about ten days later after the burning of Columbia, she reported some of the horrors of the night of February 17th, 1865, and described how some of Sherman’s soldiers had sought beds in an abandoned city hospital to sleep off their drunkenness. The hospital caught fire and burned while these men were in it, and later, other Union soldiers, finding the corpses and thinking that they were dead Confederates, “severed the heads from the bodies, caught them up on their bayonets, and danced around to the tune of ‘damnation to the rebels.’”

John and Josephine LeConte lived in a fine brick house on the corner of Pendleton and Sumter streets in Columbia. Built by the college in 1860, it was known as the “Fourth Professor’s House.” During the night and early morning hours of February 17th, Sherman’s soldiers made several attempts to burn the LeConte home. John LeConte, a supervisor of the Confederate Nitre and Mining Bureau, had been ordered away, but fortunately, a family friend named Dr. Carter was present that night, and by his help, as well as the heroic efforts of the LeConte ladies, the house was preserved from destruction. Here is another excerpt from Josephine’s letter:

“For a long time we were in imminent danger from the flames all around us as the Piazza caught, but Dr Carter was faithful, in watching the embers and extinguishing them as they caught. To show you what villains those Yankees were they screamed out to him from the street what was he putting out the fire for? Now recollect this was from the guard that was stationed around the house to protect it. About 11 o’clock at night, there was a brigade sent to the campus to protect it. Shortly after a furious knocking at the front door tempted me to go and open. As we ladies did so, a fellow flushed with wine and every other evil passion stamped upon his face sprang in and would have immediately commenced pillage but for the ubiquitous Carter who demanded his business in such an authoritative manner that the fellow abashed at seeing a man where he only expected a number of lonely women—turned upon his heel and pretended he only came to give assistance. Carter at once ordered him to furnish it which he acquiesced in after a while by sending two men …”

“The night seemed endless as we struggled against the fiery embers, while on the street below a throng of vengeful bluecoats appeared to rejoice in the travail. As each house was enveloped in flames their demoniac yells of delight coupled with the shrieks and screams of widows and orphans who sought the lawn for asylum in front of our house for protection beggars description. All night long from the Piazza and roof the women fought the flames and there were times when the panes of glass were so hot that you could not rest your hand there for any time but still we fought — and there stood that sea of upturned faces of Logan’s Corps with not one spark of sympathy for us.”

Another document that I included in my new book was a letter to the editor which was published in 1866 and which has remained virtually unknown since then. It also had to do with the burning of Columbia, and some ridiculous, false claims made by George Ward Nichols, one of General Sherman’s officers. Nichols’ war memoir came out in 1865, and two years later, he met James Butler Hickok, who would become known as Wild Bill Hickok. Nichols interviewed Hickock and published a story about this Old West folk hero in Harper’s New Monthly Magazine. The article made Hickok famous but was widely criticized for false and exaggerated accounts of the exploits of “Wild Bill.”

In 1866, Nichols had published an article in the same magazine entitled “The Burning of Columbia.” In it, he not only laid the principal blame for the calamity on Confederate General Wade Hampton, but he also suggested that most of the pillage of the city had been committed by Confederate cavalrymen under the command of General Joseph Wheeler. Wheeler’s men did reportedly take some provisions from Columbia stores just before the Confederate forces evacuated, but the overwhelming majority of the pillage, especially that of defenseless citizens, was carried out by Union troops, and there is overwhelming evidence—most of it eyewitness testimony—that Sherman’s soldiers began stealing and pillaging from the moment they broke ranks in the city. This sacking of Columbia went on all day as well as during the night of the fire, and into the following day.

In his article “The Burning of Columbia” Nichols described a conversation he had the night of the fire with a Mr. Huger, “a well known citizen of South Carolina,” and claimed that Huger confirmed to him that Wheeler’s men had been pillaging Columbia. It turns out that this “well known citizen” was Mr. Alfred Huger, the postmaster of Charleston, who was in Columbia in February 1865 with his family. In August1866, when Huger found out about Nichols’ article, he wrote an indignant response to the editor of the New York World, denying, among other things, that the conversation reported by Nichols ever took place.

One section of South Carolina in 1865 is about events and conditions in Charleston after it was occupied by Federal troops in mid-February 1865. Charleston was not burned by these soldiers, but it was thoroughly pillaged, and even the resting places of the dead were left undisturbed. It is not well known that beautiful Magnolia Cemetery was subjected to vandalism and destruction. Jacob N. Cardozo, a longtime resident of the city, reported about these events at the cemetery in his book Reminiscences of Charleston, published in 1866, excerpts of which are included in the book.

The last section of the book concerns what went on in parts of Berkeley County during February and March of 1865. It is an account written by Frederick A. Porcher, and was discovered among his papers a few years ago, so although it was written in 1868, it is “new” to us today. Frederick Adolphus Porcher (1809-1888) was a historian and a professor at the College of Charleston. Formerly, he had been a planter in St. John’s Berkeley Parish, in part of what is now Berkeley County, S.C., and he knew the whole region and its people well. About three years after the end of the war, Porcher wrote about what happened in his native parish and neighboring areas, recounting the depredations carried out by troops under the command of General Edward E. Potter and General Alfred S. Hartwell of the U.S. Army.

Porcher prefaced his narration of wartime events in St. John’s Berkeley Parish and neighboring areas with an assertion that it was the superior character of Southerners which excited the hatred of the Northern people—a hatred that ultimately caused the North to initiate and wage a war characterized by extreme—even genocidal—brutality. Porcher declared “[Northerners] felt that in the great moral power of truthfulness and devotion to principle we were their superiors—hence they hated us. They forced us into war.” He then recounts how some of that brutality was carried out in his part of South Carolina, beginning with events that transpired at Otranto Plantation in St. James Goose Creek Parish.

On February 22, a detachment from General Potter’s command, which included United States Colored Troops as well as white soldiers, arrived at Otranto Plantation, the home of Porcher’s cousin Philip Johnstone Porcher. Frederick A. Porcher quotes at length from a dramatic letter written by Philip’s daughter Marion describing the terror and plight of the defenseless women there, and the wanton destruction of their food, farm implements, and livestock.

William H. Pleasants, a Virginia scholar, published an account of the burning of Columbia in 1902 which, up to that time, had never been available. In his preface, he answered a question that some might ask today regarding books like his—and mine: “Why, by publishing a detailed description of these horrors, do you revive memories of scenes we would gladly forget?”

Pleasants gave two very good responses:

“The first answer is, that it is due to the truth of history. The Southern writers who have undertaken to write the history of our Civil conflict have not the ear of the world; the Northern writers of history, not only for general reading, but especially of school-books, are notoriously unfair. They write with a strong partisan and political bias—they misrepresent the motives and principles of action of the South, and they err, not simply by the suprressio veri, but by the suggestion falsi. A second reason why this description of the obliteration of Columbia is published is that very few, except the inhabitants of that ill-fated city, have any just conception of the horrors of that night of incendiarism and robbery; of unchecked license, of insult and every crime mentionable and unmentionable. In the histories above alluded to I doubt whether the destruction of Columbia is mentioned at all; but if noticed, it is lauded as one of the most heroic actions of their most admired general. But if heroic and splendid deeds deserve to be painted in glowing words for the admiration and improvement of mankind, surely shameful deeds should not be covered up, but displayed in their naked deformity to the candid judgment of an enlightened world.”

Hurrah Mrs. Stokes,

Very well said in a day and age where many are offended by truth. I just finished reading Diehard Rebels, which gives a very strong insight into the mind, heart and thought process concerning our ancestors who so nobly fought, suffered and died.

But how miserable it will be for those who in the end shall not see glory. We must endeavor to honour those by our continuance in the fight that we like they may be able to pass on to our posterity the truth of history and perpetuate our heritage. As I remain,

Respectfully,

R. E. Lee “Marse” Wolfe

It seems in the paragraph about the graves in cemeteries in Charleston there may be a word missing, to clear up were there violations of the graves, or not?