The halls of Congress today are seldom filled with the sound of laughter. The humor that pervaded congressional proceedings over a century ago has now given way to only angry shouts and hateful partisan rhetoric engendered by a variety of ever-growing regional, political, racial and social differences. Not that such divisions did not exist during the latter half of the Nineteenth Century, as it was a period when the nation was still struggling to find the proper path to total regional reconciliation after its bitter sectional war. However, many of those in Congress at that time, particularly those from the South, could still spare a few moments in which to add a touch of humor to their deliberations.

In 1920, the speaker of the House during the First World War, Francis “Champ” Clark of Kentucky, wrote a book entitled “My Quarter Century of American Politics.” In it, he cited the six individuals he considered to be the greatest congressional humorists of the Nineteenth Century.

Even though Abraham Lincoln evinced only rare flashes of his much vaunted wit during the two years he served in Congress, Clark, for some reason, put him at the top of his list. The others included Representatives Thomas Corwin of Ohio, James Knott of Kentucky, Francis Cushman of Washington and Samuel Cox who had represented areas in both New York and then Ohio where he joined Clement Vallandigham as a Peace Democrat during the War of Secession.

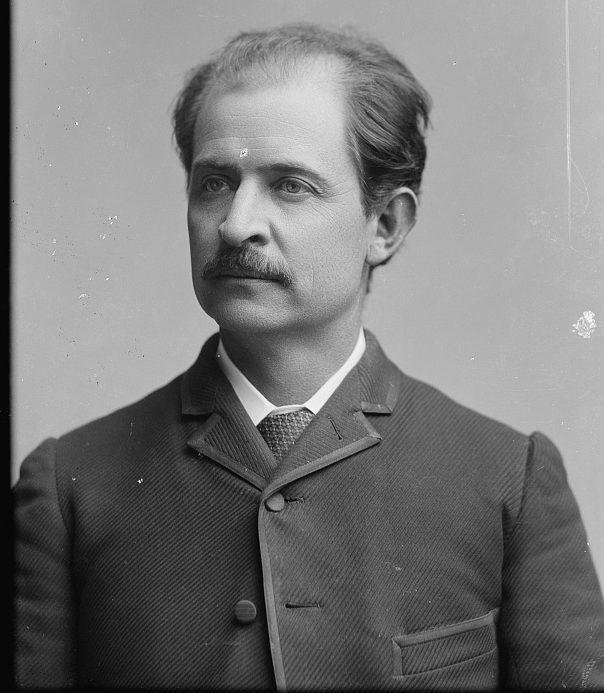

Clark’s selection as the best representative of true Southern humor, however, was a congressman and Confederate veteran from Mississippi, John Mills Allen, who represented the state’s First District in the United States House of Representatives from 1885 to 1901, but who few probably remember today. Those who do still refer to him as “Private” John Allen, a sobriquet Allen liked to say was gained during his first campaign for Congress in 1884.

Allen claimed that in the election, he ran against a general from the recent war. In his campaign speeches at that time, Allen told the audience that anyone who had been a general during the recent war should vote for his opponent, but all those who were privates who guarded the generals while they slept should vote for Private John Allen. Allen said he won a landslide victory and that following the election, the title “Private” stayed with him throughout the rest of his life.

A look at the records of congressional elections in Mississippi from 1884 to 1898, however, reveals that Allen’s first Republican opponent for Congress was not a general, but Confederate Colonel Green C. Chandler who had been the first commanding officer of Mississippi’s 8th Infantry Regiment at the start of the war. Allen was was correct that he did win an overwhelming victory over Chandler by receiving more than eighty per cent of the votes.

It would seem though that Chandler was more interested in politics than in military affairs. Just before he had been made colonel of the 8th Regiment, Chandler had petitioned Governor John Pettus of Mississippi for appointment as district attorney of the state’s Eighth Judicial District. The office had become vacant after District Attorney John Terrol was commissioned an Army captain by President Davis. Then, in November of 1861, Chandler was elected as district attorney and resigned his commission.

As for Allen, he was born in Tishomingo County, Mississippi, in 1846 and in March of 1862, four months before his sixteenth birthday, he traveled to Corinth in neighboring Alcorn County to enlist as a private in Company “D” (the “Lowrey Rebels”) of the 32nd Mississippi Infantry Regiment. Allen served in that unit as a private throughout the war and participated in every major battle fought by the 32nd Regiment from Chickamauga to Atlanta, as well as later with General Hood in Tennessee. Allen also saw action in North Carolina where he was wounded and taken prisoner in 1865.

Following the war, Allen returned to Mississippi and graduated from the University of Mississippi’s School of Law in 1870. He began his law practice in Tupelo and from 1875 to 1879, he served as the district attorney for Mississippi’s First Judicial District. Five years later, he made his first run for Congress where he served for eight consecutive terms.

After Allen declined to run for reelection in 1900, President Cleveland appointed him to be the United States Commissioner for the 1904 St. Louis Exposition. He then returned to his law practice in Tupelo until his death in 1917.

As an example of Allen’s wit, when he first entered Congress in March of 1885, he often recounted one of his earliest cases in Tupelo. In the story, Allen said that shortly after the War, an old former slave named Pompey came to his office and said that he was about to be arrested for stealing two hams. When Allen inquired if he had actually committed the crime, Pompey confessed to taking the hams from the local store. When Allen asked if there had been any witnesses to the act, Pompey replied that he had been observed by “two old coonass white men” who were sitting in front of the store.

Allen sadly told the man that under the circumstances there was nothing he could do for him, but Pompey offered him ten dollars and begged him to at least try . . . and Allen finally agreed. The trial was held before a virtually uneducated judge named Johnson from whose courtroom very few defendants, particularly those of color, ever managed to escape the maximum punishment.

After the prosecution had presented its case, Allen arose and informed Judge Johnson that it would be useless for him to argue his client’s position in the face of such overwhelming evidence. He added, however that while the judge’s knowledge qualified him for a position on any bench in the land, even one at the nation’s Supreme Court, he may have forgotten one item of old English law which clearly decided the case in favor of his client. Allen then pulled a worn copy of “Caesar’s Gallic War” from his pocket and read the opening line, “Omnia Gallia in partes tres divisa est.”

Tossing the book on the table and taking his seat, Allen stated that the well-established law clearly decided the case and the court must acquit the defendant. The judge, according to Allen, was momentarily nonplussed but ultimately said to Pompey, “I know you stole them hams, but by the ingenuity of your lawyer, I’ve got to let you go.” He then added, “Git out! And if you ever come here again, lawyer or no lawyer, you’ll git six months.”

Allen’s humor was also highly praised in a 1947 American Bar Association Journal article written by an award-winning attorney from Memphis, Tennessee, Walter Armstrong. In the piece entitled “ ‘Private John Allen” A Lawyer Who Had ‘The Saving Grace’,” Armstrong wrote that Allen’s witticism’s took much of the bitterness out of many debates of his day, as well as greatly helping to close the bloody chasm that had divided the nation just two decades earlier.

The article also cited a speech by Allen that Armstrong termed, “The most sustained medley of wit, humor, exaggeration and pathos in the annals of Congress.” The speech was made in February of 1901, a month before Allen left the House of Representatives, and in it he urged that a national fish hatchery be established in his home town of Tupelo. One line from the speech stated that, “Fish will travel over land for miles to get into the water we have at Tupelo . . . and millions of unborn fish are clamoring to this Congress today for an opportunity to be hatched at the Tupelo hatchery.” Allen’s wit was successful, and the hatchery was not only eventually built and named in his honor, but still exists to this day and was recently named by the U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service as America’s hatchery of the year.

Armstrong added, however, that Allen should not be remembered for his wit alone, as he was also a wise and experienced statesman. He further said that Mississippi produced some of the nation’s ablest members of Congress after the War of Secession, and that Allen must be included among them. He closed by saying that Allen well deserved the epitaph carved on the simple stone above his grave at Glenwood Cemetery in Tupelo which reads, “John M. Allen: Gentleman, Patriot, Sage.”

As a sidebar, “Private” Allen never wrote his memoirs and no one has ever bothered to write his biography. In relation to how he gained the cognomen “Private,” virtually all accounts of his life merely state that he ran against some former general during an early campaign for a seat in Congress, but no name is ever given. Armstrong identified the individual as Brigadier General William Tucker, the former commander of the 41st Mississippi Regiment. While it is true that General Tucker had made an unsuccessful run for Congress in 1880, he certainly could not have run against “Private” Allen four years later, as Tucker was murdered at his home in Okolona, Mississippi, in 1881.

Armstrong, however, was most prescient in his writing seventy-five years ago concerning the anti-Southern conditions that existed at that time. His article clearly shows that the current effort to dishonor not only the the Confederacy but the South in general did not begin a little over two decades ago in South Carolina with the furling of the Confederate Battle Flag in Columbia or even the black church shooting in Charleston five years later that touched off Confederate monument mania.

Armstrong wrote in the preamble to his 1947 article on Allen, “Today, there is a concerted and sustained attack on the ideals, ways of thought and manner of life in the South. The leaders of this attack are leftist advocates of radical changes, many of which are undesirable and impractical. They are hostile to the South, as they consider it the strongest, if not the last, citadel of the form of government and adherence to the constitutional limitations which our fathers founded, and in which some of us still believe.”

Just a small note. Cleveland was not president in 1900. McKinley was. But if it was the Union veteran McKinley who appointed Allen commissioner for the St. Louis exhibition, we should look on that as an example of the reconciliation so many of us have turned our backs on today.

Mr. Alioto:

Somewhere in my notes there was a line about Allen having been appointed by Cleveland as a U. S. Commissioner for the St. Louis World’s Fair, but I cannot find it. Perhaps Cleveland had suggested Allen prior to leaving office. In any case, it could not have been McKinley either, as as he was assassinated at the Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo, N.Y., in 1901, which meant that Teddy Roosevelt would have made the appointments for the St. Louis fait of 1904.