Originally published in Southern Partisan in 1979.

Some forty years ago, H. L. Mencken and one of his cronies set out to study the “level of civilization” in each of the (at that time) forty-eight states. They put together a variety of quantitative indicators of health, wealth, literacy, governmental performance, and so on, and triumphantly announced in the American Mercury that “the worst American state” was Mississippi. Alabama was next, followed by the other eleven Southern states, with only New Mexico (at number forty) breaking up the otherwise solid South. The four “best” states were Massachusetts, Connecticut, New York, and (believe it or not) New Jersey, in that order.

A similar study, published just last year, is much more sophisticated, methodologically, than Mencken’s, and it has replaced his word “civilization” with the more modish phrase “quality of life.” But it uses basically the same sorts of indicators–measures of economic well-being and governmental services–and it came up with substantially the same results: the Southern states were all at the bottom of the scale. Once again–or still–the “quality of life” in the South is the poorest in the country.

Of course Southerners have been familiar with criticisms like this for a long time–since the 1850s, anyway. Those who’ve felt obliged to defend the South have usually replied with variations on the theme that man doesn’t live by bread alone. One of the most eloquent statements of this position came from the Vanderbilt Agrarians, who published their manifesto, I’ll Take My Stand, at just about the same time Mencken was collecting his statistics. Their philosophy can be summarized by the Southern folk maxim that success is getting what you want, but happiness is wanting what you get.

Now, certainly there have been versions of the good society besides just one in which everybody is happy. Samuel Johnson could scoff at happiness as a criterion for quality of life. A bull, he said, standing in a field with lots of grass and a cow nearby probably thinks he’s the happiest creature alive. But a contributor to a recent symposium on the “quality of life” concept has pointed out that nearly all discussions of the concept, lately, have taken it for granted that a society’s quality of life means the extent to which it makes for individual happiness–or satisfaction–or what the economists mean by their special use of the word “welfare.” Mencken used the same criterion: he quoted J.B. Bury with approval, “a condition of general happiness is the issue of the earth’s great business.”

And certainly, as somebody said once, happiness is no laughing matter. I’ll come back to some of the problems with using individual happiness as a defining measure of the “quality of life,” but for the moment, let’s accept the general consensus that it should be so, or at least that happiness is an important component of the concept.

One development in the social sciences since Mencken’s time, and one with an important bearing on this question, is the elaboration and refinement of sample survey techniques and of social-psychological measurement. It is no longer true that “of happiness and despair we have no measure.” We don’t have to assume anymore that wealthy people are happier than poor ones, we can show this is so, and, equally important, we can show when and under what conditions it is not so. And when we ask the question, What is the worst American state? we can use an entirely different sort of indicator: direct, social-psychological measurement of satisfaction. When we do this, we get some interesting results.

Now, even if we restricted ourselves to the kind of things governments ordinarily collect statistics about, there are reasons to doubt the perennial conclusion that the quality of life in the South is relatively poor. We find striking differences in the South’s favor, for example, in suicide rates, in rates of mental illness, in rates of alcoholism, and heart disease, and other stress-related health problems. Each of these differences is open to several interpretations, of course, but taken together they suggest we shouldn’t jump to conclusions about the quality of Southerners’ lives. There is also the matter of migration statistics. It’s well known by now, I suppose, that there has been net in-migration to the South for whites for some time. I’m told that for the last three years there’s been net in-migration for blacks as well. The social and demographic characteristics of these immigrants suggest that many of them are responding to something more than just economic opportunity.

It’s when we turn to the survey evidence, though, that the contradictions are really striking. Merle Black, a Texan who teaches political science at North Carolina, looked at sample data from the citizens of thirteen states, including the five Southern states of North Carolina, Alabama, Texas, Louisiana, and Florida. Everyone was asked this question: “All things considered, would you say that your state is the best state in which to live?” Overall, about 63 percent of the respondents felt they were currently living in the best state. But there was huge variation in this figure from one state to another. By this measure, the “best” of the thirteen states examined was, well, North Carolina, where more than 90 percent of the natives felt their state was the best. Alabama was the next

best, followed by the other Southern states. Only California (fourth of the thirteen) ranked higher than any Southern state. The “worst” state, in the opinion of its residents, was Massachusetts–Mencken’s “best” state, where only about 40 percent of the sample felt that their state was the best, “all things considered.” New York was also one of Mencken’s “best states,” but it does just about as poorly. It looks as if my fellow Tennesseean, Brother Dave Gardner, may have been right when he said that the only reason people live in the North is because they have jobs there. (He said he’d never heard of anyone retiring to the North.)

For the thirteen states Black looked at, the rank-order correlation between Mencken’s index of “civilization” and Black’s measure of satisfaction was a negative .76. The Northeastern states were civilized and discontent, the Southern states happily backward, and the Midwest was–as usual–mediocre all the way around. Only California was above average in both respects, and only South Dakota, below.

In my own work, with a series of Gallup polls dating back to 1939, I’ve found very similar results. When Americans are asked where they would most like to live, they could live anywhere they wanted, if a constant finding is that Southerners like it where they are better than any other Americans, except possibly Californians.

Isn’t this odd? Why don’t we Southerners realize how bad o we are? Or, for that matter, why don’t Northeasterners appreciate how well o they are? Looking for expert opinions, I polled a small sample of my colleagues in the Sociology Department at North Carolina. A few of them–transplanted Yankees–suggested that Southerners are too ignorant to know any better. But that just won’t do. Most of the people who said this were PhDs–who can be presumed to “know better,” and who still choose to live in North Carolina. Besides, Merle Black’s data show that, among North Carolinians generally, those with more education, more opportunities for travel, and so forth, are no less likely to regard North Carolina as the “best state” than anyone else. In Massachusetts, it’s true that the people who “know better” like their state less, but that’s not the case in the South–at least not in North Carolina. As a matter of fact, nothing makes any difference in the generally high evaluation that North Carolinians have of their state. Merle Black shows that black North Carolinians are as enthusiastic as white ones, rich ones as enthusiastic as poor ones (but no more so), urban folk like the state as well as rural ones…. Only recent migrants (and I emphasize recent) have an evaluation of the state which is less than overwhelmingly favorable. It looks as if Thomas Wolfe was onto something when he wrote in his notebook: “New England is provincial and doesn’t know it, the Middle East is provincial, and knows it, and is ashamed of it, but, God help us, the South is provincial, knows it, and doesn’t care.”

No, the paradox these data present can’t be explained by saying that Southerners don’t know any better–although, of course, some don’t. I think part of the contradiction is more apparent than real. What is a poor and ignorant Tarheel telling us when he says that North Carolina is the “best state?” Why, he’s telling us that it’s better to be poor and ignorant in North Carolina than in any other state. Sure, he’d rather be rich, but he probably doubts that he can really improve his economic condition by leaving. If he thought that, he’d probably leave.

Obviously it’s better to be rich than poor–and if it’s not obvious, there’s plenty of evidence to prove it. It’s not so obvious that it’s better to live in a rich state than in a poor one. In fact, there are good reasons to suppose that living in a rich state makes rich folks feel less rich, and poor folks feel poorer. So any given individual may be psychologically “better o ” in a state like North Carolina, or Alabama, where the average individual is worse o .

Besides that, the kind of economics and politics that can make a state healthy, wealthy, and wise–”civilized,” as Mencken would have it–can have at least short-run effects that people experience as debits in the “quality of life” ledger. For example, New York spends twice as much per pupil on education as North Carolina. Score one for the quality of life in New York when those pupils finish school. But North Carolina’s taxes are about half of New York’s per capita. Score–how much?–for the quality of life in North Carolina right now. Workers earn half again as much in Illinois as in South Carolina. But they’re on strike for an average of four to ten times as many days in a given year–often with negative consequences for other people’s “quality of life.” Connecticut’s homicide rate is only half of Virginia’s. But many Virginians would find Connecticut’s gun control laws an obnoxious interference with their personal freedom. New Jersey is more highly industrialized than Arkansas. But Arkansas’ air is cleaner.

My point isn’t that the Southern states are preferable in each of these comparisons. (I, for one, would be glad to pay higher taxes to improve education in North Carolina: I have to teach graduates of North Carolina high schools.) I am just pointing out that a given individual can quite rationally be unwilling to trade a clear and present good thing for a distant and hypothetical benefit–which will probably accrue to someone else in any case. It’s perfectly reasonable to want to be born in New York–you’ll have a better statistical chance of surviving to adulthood, getting a decent education, and entering a high-paying occupation. But it may also be reasonable to want to live in North Carolina–your money will go further and you’ll enjoy life more. (I think the migration statistics are telling us that people are starting to notice this.)

Anyway, if we recognize that workers in what we can call the “Menckenian” tradition are measuring one thing and that the people who talk about “satisfaction” are measuring another, we’ve gone a long way toward explaining the apparent discrepancies. There are some interesting questions left, though. For instance, what is it about the Southern states that their residents like so much? I’ve already suggested a few possible answers, but I want to press on–without fear and without research, as somebody (I think Carl Becker) said once–I want to press on to argue that there are things that everybody wants (or almost everybody) and that Southerners have more of. I think we can explain why Southerners like their communities and their states so much–and it’s not that the climate affects their brains directly (as one of my colleagues suggested).

Let me describe a whimsical “quality of life” index I constructed, one I think does a fantastically good job of predicting which states are lovable and which aren’t. This index has two components: mean winter temperature and robberies per 100,000 population in 1971. These two factors explain nearly two-thirds of the variation in the ranks of the states on Merle Black’s “best state” question. Obviously, people like safe, warm places.

This finding tells us more than that, though. It’s a roundabout way of telling us what’s important to people when they’re deciding whether someplace is a good place to live. Each of those components–climate and robberies–is standing in, so to speak, for a host of other characteristics. The average winter temperature has all sorts of implications for people’s way of life (or “lifestyle,” if you prefer). And the robbery rate tells us a lot about personal relations and social stability. I suggest to you that this is the sort of thing people have in mind when they say that North Carolina is the “best state”–or that Massachusetts isn’t.

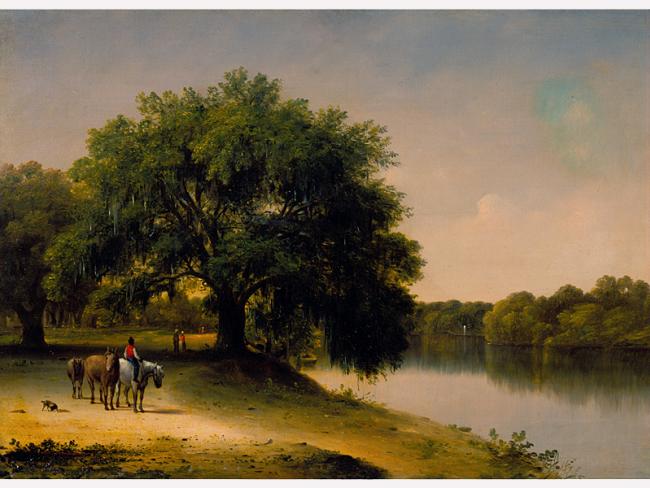

About three years ago, another fellow and I asked a sample of North Carolinians, “What would you say is the best thing about the South?” More than two-thirds of our respondents mentioned natural conditions–the benign climate, the clean air, the forests and wildlife, the easy pleasures of a life lived largely outdoors. There’s nothing uniquely Southern about this taste: the frequent mob scenes in our nation’s parks tell us that. But Southerners can indulge themselves more easily and more often than their less favored brethren–and our data show that that’s important to them.

Incidentally, I don’t think it’s accidental that the climate hasn’t turned up in most “quality of life” indexes. Most of them have been constructed by intensely practical men, concerned with policy–and there’s not a whole

lot the government can do about the weather. At least not yet. Thank God. Dr. Johnson wrote: “How small of all that human hearts endure,/ That part that kings or laws can cause or cure”–words to make a political scientist gnash his teeth, but we need to keep them in mind when we talk about what makes people happy.

The other component in my little index, the number of robberies per 100,000 population, reflects another major concern of Americans: what was called, not too long ago, “crime in the streets.” Poll after poll shows that many Americans just don’t feel safe. Now it has been almost traditional to put the homicide rate into “quality of life” indexes–and the South doesn’t do too well on that score. But the thing about homicide, especially in the South, is that it’s not “in the streets.” It’s often in the home and usually between friends, and even in the South it’s pretty unusual. What’s more common, and what people are scared of, is being robbed, mugged, raped, or burgled by a stranger. And North Carolina’s robbery rate is only one-tenth of New York’s.

I think in some ways the most important effects of the robbery rate (and all that it implies) are indirect–the suspicion and distrust that follow from it, the absence of easy and cordial interaction with strangers. This kind of thing is important to people, too. When we asked what the best thing about the South was, half of our respondents said that the people were: that Southerners are friendly, they’re polite, they take things easy, they’re easy to get along with. Two recent studies from the University of Michigan document the obvious fact that personal relations are important to all Americans–we all rely on face-to-face interaction for the greater part of the satisfaction we get from life. But the North Carolinians in our poll seem to feel, and I agree with them, that the texture of day-to-day life is pleasanter in the South–particularly in fleeting, secondary interactions (like those with salesclerks and secretaries and cabdrivers and policemen–and I regret to say–students). A good part of nearly everybody’s day is taken up with precisely that kind of interaction. It might as well be pleasant.

Here again, the effects of government and economy are really pretty remote. The kinds of things that Mencken and other toilers in that vineyard are measuring don’t have much to tell us about this aspect of “quality of life.” Southerners know what Mencken was trying to tell them; very few of our respondents mentioned politics or economics when we asked them what they liked about the South, and nearly a third mentioned them when we asked what they liked least about their region. All in all, I read these data to say that state and local politics don’t make much of an impression on most folks, just living day-to-day, except as an entertaining sideshow (perhaps especially entertaining in the South).

If I had the time–and the weather weren’t so nice–I could probably go on to explain the rest of the variation in the lovability of the states. I’d start with observed facts (like that homeowning is an important value for most Americans) or with sound theoretical propositions (like that people are more comfortable in culturally homogeneous communities), and I’d translate those into measures we could look up in the City and County Data Book. But I hope I’ve made my point–or rather points. Let me spell them out, to wrap this up.

First, we need to be clear whether we’re talking about the “quality of life” of a given person or of the average person. Second, nearly all “good things” come at a price, and we need to be sensitive to that. Third, we can’t impose our own definition of “good things” on people–they will perversely continue to use their own. Fourth, there are many important aspects of the good life that policy-makers can’t do anything about. And my last observation is that Providence has seen t to endow the South with more than its share of this bounty. We can be thankful for that.

if true, my family has been in NC since the 1730s. born in raleigh, id say I saw noticeable ethnic changes in the 90s. i know numerous doctors and tech people had migrated down from the northeast a few decades prior. james taylors parents were from new york? as a raleigh native from the late 60s it just seemed to me like any place that had a Walmart and was in good economic position. RTP planners did well. i was able to move to northern Nevada for 10 years in the early 2000s. the weather was less humid and frankly perfect. it just seemed a relaxed easy-going place where gambling didn’t seem to ruin everyone every day. it was mostly white , some Asian and Latinos and a few blacks. it was a nice change from raleigh. i was also able to travel the northern midwest…Minneapolis, Greenbay, Manitowoc, Sault St Marie….and aside from brutal winters, their lake life seemed very local and ‘built upon’ in a sense, like parts of the south used to be. the more I listen to brion the more true federalism seems proper.

James Taylor’s mother I am sure was from Massachusetts .

I assumed his dad was as well. Buy I have read his dad ( if his ancestors on that side of the family) hailed from somewhere in South Carolina

James Taylor’s mother I am sure was from Massachusetts .

I assumed his dad was as well.

But I was mistaken. I thought I had read he was from South Carolina. However I just read the Wikipedia article about James Taylor’s s father. It says he was born in Morganton, NC attending college at UNC Chapel Hill