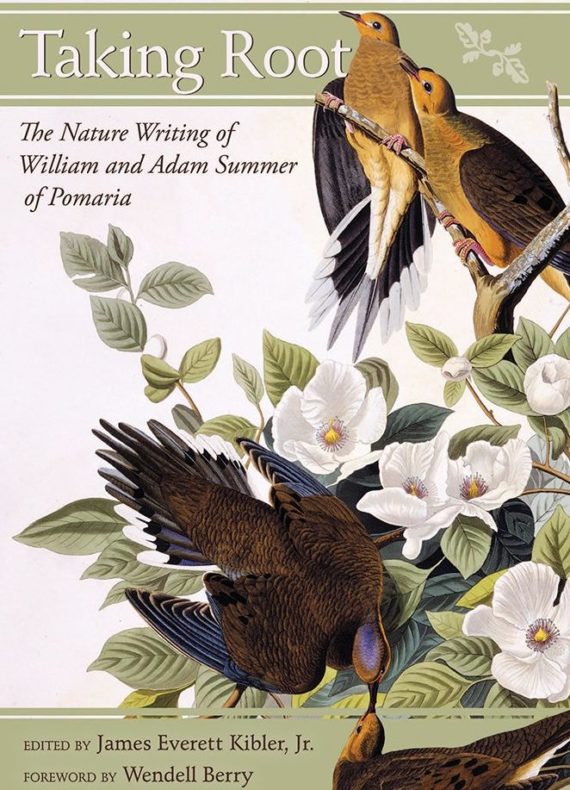

A review of Taking Root: The Nature Writing of William and Adam Summer of Pomaria by James Kibler (editor) and Wendell Berry (Foreword) (University of South Carolina Press, 2017).

Perhaps land is more important to the Southern tradition than any other aspect of the region’s experience. Historians continue to grapple with questions that ask how Southerners understood land and nature. In fact, no honest scholar of the South’s intellectual history can deny the overwhelming role of land in shaping how Southern people viewed their world. Dr. James Everett Kibler’s diligent study into the life and career of South Carolina nurserymen and botanists William and Adam Summer contributes much to the larger, long-view story of Southern agrarianism. Kibler brings to light the historical significance of the Summer brothers, gentlemen whom horticultural scholar James Cochran refers to as among the most important plantsmen of the antebellum South.

In his introduction to the Summers’ essays, Kibler rightly explains the significance of their Pomaria Nursery. The nursery propagated hundreds of varieties of fruit adaptable to the South’s climate, including several cultivars of fig, pear, apple, plums, peaches, as well as a multitude of ornamental plants suited to the region’s environment. Throughout South Carolina and many of her sister states, plants from Pomaria dotted the home landscape. In many ways, the Summers were ahead of their time. They wrote about land conservation long before there was a United States Department of Agriculture to deem it worthy of the farmer’s attention. Their published essays argued in favor of right moral treatment of both land and livestock. The brothers argued for balance, an approach to land use that did not take from nature without putting something back in. This was sustainable agriculture at its finest. Unlike many of their contemporaries who planted cash crops on the same acreages each year, depleting soil quality in turn, the Summer brothers, like Jefferson decades earlier, preferred to see land through the lens of good stewardship, as the key to an independent, republican society based on small and local sources of production. Pomaria, more than just the home of the Summer family, came to represent in microcosm an agrarian vision of the South’s future.

A reading of the Summers’ essays helps us rediscover the roots of the South’s agrarian philosophy. Contrary to the New England transcendentalism of Emerson and Thoreau, the Summers exemplified a view of nature as the Creation, of man as the created, a creature of limitations. Nature, rather than being separate from the human experience, is an essential part of it. Man derives his sustenance from land well tended and nurtured, and thus the land becomes an extension of himself. It is land that provides a sense of place and belonging. In many ways, Adam and William Summer continued to see nature similar to how historian Andrea Wulf described Washington and Jefferson, that is, as gentlemen who saw the American natural world as the greatest symbol of individual liberty and republicanism.

Stewardship is a central theme of the Summers’ writings. In his introduction, Kibler highlights an 1854 essay from Adam Summer entitled “We Cultivate Too Much Land.” Summer began the essay thus, “When man was first commanded to go and dress the earth, it was a mandate which did not imply waste, and desecration, and heedless greediness in monopolizing thousands of broad acres, but he was ordered to cultivate, beautify and preserve that which, after it was finished, was pronounced by the Creator—good.” (116) The essay is a plea for agricultural diversity, localization of the economy, and better forms of land use. One might say that Summer exemplified an important, yet often forgotten, Southern agrarian land ethic.

This seminal collection of nature writings, so ably selected by Kibler, an exemplary, practicing agrarian in his own right, reminds us that much of the modern interest in local food, sustainable agriculture, and homesteading are best understood when situated in a broader, older context. The history of land conservation, sustainability, and movements in favor of small, local farming would be incomplete without studying those writers and thinkers of the Old South who, long before Wendell Berry, or even the Fugitive-Agrarians, envisioned America as a country of individual families living out their days on flourishing homesteads. The Summer brothers, however, did not simply write about what they believed: they put their philosophies to work. Countrymen across the South established plants from Pomaria nursery at their homes in hopes of beautifying the landscape and making their farms more productive by propagating species well suited to the local environment. To be sure, the nature writings of the Summer brothers challenge the idea that agrarianism was little more than an unrealistic, idyllic goal. They call to mind an America, indeed a South, that has already existed as a dynamic, fulfilling, and unapologetically agricultural society.