The date of the latest federal holiday, June 19th, was touted as the one marking the end of slavery in America. While few today would argue with the idea of honoring emancipation, the selection of that date in 1865 leaves much to be desired. If one truly wanted to commemorate the legal end of American slavery, the date for such a memorial should have been December 6th . . . the day in 1865 when the Thirteenth Amendment to the Constitution was finally ratified and actually accomplished full and legal emancipation.

June 19th is merely the day in 1865 when Union troops under the command of Major General Gordon Granger landed in Galveston, Texas, a little over a week after Confederate Major General Kirby Smith effectively ended the War by surrendering the Army of the Trans-Mississippi. After General Gordon’s arrival, he immediately issued General Order Number Three which proclaimed that the slaves in Galveston were now free. As the Thirteenth Amendment had not yet been ratified, the general had no legal authority to issue such an order other than basing it on Lincoln’s two-year old Emancipation Proclamation.

There was a major problem with that however, for even if Lincoln had the legal authority to free people in another nation, his 1863 proclamation clearly stipulated that “slaves within any State or designated part of a State, the people whereof shall then be in rebellion against the United States shall be . . . free.” The relevant words in this case being “then in rebellion,” but as the War was over and the Confederate government no longer existed, none of the Southern States, including Texas, were still, as Lincoln had termed, “in rebellion.”

Speaking of the Thirteenth Amendment, it is also interesting to note that even after fighting a four-year war to maintain the supremacy of the Federal government over the rights of the States and all of Lincoln’s endless rhetoric about preserving the unity of the nation, the writers of the Amendment still saw fit to state that “Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude . . . shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to THEIR (emphasis added) jurisdiction.” The writers had also added the now controversial phrase that “involuntary servitude” would be allowed as punishment for those duly convicted of crimes . . . which, of course, permitted various forms of convict labor, such as the infamous “chain gangs,” to still exist throughout the nation.

Moreover, the slavery amendment also called into question, even in Lincoln’s own mind, the legal authority of the Emancipation Proclamation. Lincoln himself termed his document to be only “a fit and necessary war measure for suppressing said rebellion,” and also added that it was “believed to be an act of justice, warranted by the Constitution” but cited no specific constitutional references. However history now considers it to have been an actual executive order with the force of law. If so, one might then also question Lincoln’s motivation for proposing a much different type of constitutional amendment on emancipation just a month prior to the effective date of his proclamation.

At the end of the War’s second year, events continued to be going going badly for Lincoln. His party, while maintaining control of Congress, had lost twenty-seven House seats in the 1862 elections. Internationally, the threat of British and French military intervention was still very real and on the war front, the fighting, particularly in the East, had produced no major victories for the North. His efforts to capture the Confederate capital of Richmond by campaigns both down the Shenandoah Valley and up the Virginia Peninsula had resulted in a string of stinging Union defeats. Moreover, Lincoln was being constantly pressed by the abolitionist Radical Republicans to take some positive step towards ending slavery. Such urging finally forced him to prepare a proclamation to that effect which he said would be issued at the appropriate moment.

Such a moment arrived that September 17th in Maryland when the Union and Confederate forces clashed in a monumental battle at the town of Sharpsburg. The fighting along Antietam Creek caused almost twenty-five thousand casualties, the majority of whom were on the Union side, and while the battle was considered a tactical draw militarily, the North still could claim a strategic victory as it did halt Lee’s northward advance. Five days later, Lincoln finally issued his Emancipation Proclamation which was to take effect a “hundred days” later. but no explanation was given for the more than three-month delay.

Even though slavery was supposed to end at the beginning of the coming year in the States then “in rebellion,” but not those still in the Union or in areas controlled by the Union forces, Lincoln must have had some doubts as to the document’s actual effectiveness. Just a month prior to the date the proclamation was to go into effect, he proposed in his 1862 message to Congress a much different and highly detailed plan for gradual emancipation.

His plan called for a constitutional amendment, which would have been the thirteenth, mandating in the first article that slavery in all the slave States must end no later than January 1st, 1900. Despite Lincoln’s public denial that the eleven Southern States had actually seceded and formed a new country, but were merely in rebellion against the United States, he realized that a new constitutional amendment would require those States to rejoin the Union and participate in the ratification vote. If adopted, the amendment would give each slave State, including the four that had remained in the Union and the new State of West Virginia, thirty-seven years in which to devise some form of full emancipation.

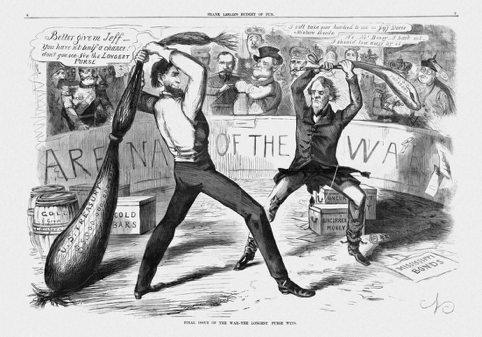

Ever with an eye on the Northern economy, Lincoln then laid out his detailed scheme in the second article as to how the staggering dollar cost of the War could be ended and peace restored. This would be accomplished at less cost by compensating all the slave States for emancipation through reparations to be paid in the form of interest-bearing government bonds. There was also a clause indicating that if any State reneged and reinstituted slavery at any time, their punishment would be the repayment of both the bond’s principal amount and any interest received. Oddly enough, there was no threat included of any further governmental action if a State reintroduced slavery. The final article called for additional; federal funds to be used for colonizing the freed slaves in some place of their choice outside the United States.

There was, however, little chance of either Lincoln’s amendment or the South’s return to the Union being seriously considered by the Confederacy. This does not mean though that the idea of gradual emancipation was not also a policy of President Davis and most other responsible Confederate leaders. Some, such as Secretary of State Judah Benjamin and Major General Patrick Cleburne, even went a step further and advocated immediate manumission for any slave willing fight for the Confederacy . . . an idea that was ultimately adopted in the closing days of the War, but by then it was a case of too little and too late. The primary problem was that the South was not only unwilling to accept emancipation at the expense of independence, but they also saw through the duplicity in Lincoln’s reparations and colonization schemes.

At the time of the War Between the States, virtually all U. S. federal tax revenues were derived from the tariffs collected on foreign imports . . . the excise tax. This had been one of the underlying causes of the War, as up to three-quarters of such taxes were collected at Southern ports and such a loss of tax revenue could not be tolerated by the Union. To add to the North’s financial woes, with the Southern States out of the Union, it also reduced the exports of the United States to less than half of what they had been. Therefore, if the South returned to the Union it would merely reinstate the same tax imbalance. This status quo would then mean that the South would not only have to pay wages to their former slaves or their replacements, but would also have to provide most of the tax money for the reparations they were to receive. A truly no-win situation. If Lincoln had been really serious about his proposed amendment, he might have also suggested some new forms of taxation that would spread the burden of financing the Federal government over the entire nation, such as an income tax or a value-added tax.

In his annual message of 1862, Lincoln also alluded to the “fiery trial” through which the nation was then passing. He then urged the adoption of his proposed amendment which he stated would not only end the War, save vast sums of money and reunite the country, but would lead the again united nation to a golden era of peace, prosperity and population growth. On that score, Lincoln even gave specific projections as to the vast increases in population he envisioned up to 1930 but as is the case with most governmental models, Lincoln’s were far off the mark. He predicted that a reunited country would see a population of over well over a hundred million million people by 1900, while the actual number for that year was only a little over seventy-six million. The discrepancies continued to widen greatly and for 1930, Lincoln’s projection of over a quarter of a billion population was more than twice the actual number of Americans in that year.

Lincoln’s impassioned “fiery trial” rhetoric fell on deaf ears in both the South and Congress, however, and the idea of gradual emancipation with full compensation for all the slave States went nowhere. The Republicans did want to ensure emancipation by a constitutional amendment though and during the following December, a resolution for enacting a Thirteenth Amendment was drafted in Congress by Representatives James Ashley of Ohio, James Wilson of Iowa and Senator John Henderson of Missouri. While the Senate passed the final form of the measure in April of 1864, it was not until the following January that it was adopted by the House of Representatives and then finally ratified on December 6th when Georgia cast the needed twenty-seventh vote.

It should be noted that while Lincoln’s home State of Illinois had cast the first vote for ratification on February 1, 1865, eight of the eleven Confederate States were among the three-quarters of the thirty-six States then needed for ratification, with Florida voting to ratify twenty days later and Texas in 1870. The only former Confederate State to reject the Amendment was Mississippi and while that State held a symbolic vote to ratify in 1995, it was not certified until 2013. However, two Northern slave States, Delaware and Kentucky, as well as New Jersey, had also initially rejected the Amendment in 1865. However, New Jersey did vote to ratify it a year later, but Delaware delayed its ratification until 1901 and Lincoln’s birthplace of Kentucky did not ratify until 1976.

During the time the Thirteenth Amendment was being considered, Lincoln’s doubts about his Emancipation Proclamation began to grow stronger, as he feared that it might be found unconstitutional if taken to the federal courts. While he also had reservations about the political effect of the amendment that had been passed by the Senate, Lincoln finally backed the legislation and made it a major plank in his 1864 reelection platform. Fortunately for Lincoln, the Northern voters also favored the amendment. and he was swept into a second term. However, a bullet fired at Ford’s Theater in Washington on the night of April 14th denied Lincoln from ever seeing true emancipation finally becoming a reality for black Americans.