Slavery, we are repeatedly told, is America’s “original sin.” But unlike the effects of Biblical original sin, there is no possible atonement. The Left and its racial Grievance Factory will never let original sin be blotted out or separated from American politics. In the words of Yale historian David Blight, there exists a “the living residue” connected to African slavery that is “ever-present yet ever-changing in our world.”[1]

According to research by Heartland Institute scholar Duke Pesta, students entering American colleges “are convinced that slavery was an American problem that more or less ended with the Civil War, and they are very fuzzy about the history of slavery prior to the Colonial era. Their entire education about slavery was confined to America.”[2]

This focus is not by accident or an example of dogged American insistence on national uniqueness. By casting slavery as an American sin with an eternal legacy, power is exercised over a guilt-ridden citizenry. The Grievance Factory can convince otherwise intelligent people that “the living residue” of slavery is responsible for the death of George Floyd and that monuments to heroes—some of whom helped end American slavery—should be torn down in the name of cultural revolution. All this despite evidence that Floyd was a career criminal, had just victimized a store with counterfeit money, was non-compliant with a lawful police investigation, and had imbibed a powerful dose of methamphetamine and fentanyl.

The Grievance Factory can also ensure that white Americans continue to support affirmative action in university admissions, government set asides for minority contractors, and “diversity” programs in private business that guarantee favored minorities advancement. This entrenched shakedown system—the envy of La Cosa Nostra—pumps dollars and willing puppets back into the advocacy and political arms of the Left and the Grievance Factory. Their power expands exponentially.

Slavery, of course, was not a unique American institution—it was a universal human institution touching all continents of the globe. American Book Award finalist Milton Meltzer in his Slavery: A World History points out that many historians actually considered the institution as “a step forward to the development of civilization” inasmuch as primitive people typically killed all warriors from a defeated tribe because they did not have the resources to feed additional mouths.[3] As man learned how to domesticate animals and farm, captives could be spared and enslaved.

In the ancient world, slavery existed in Mesopotamia—the region situated between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers in what is modern-day Iraq. The inhabitants of this “Cradle of Civilization” produced the first written languages as well as recognizable cities. Slavery was practiced in Egypt, Palestine, Greece, and Rome. In these cultures a person could be enslaved by being on the losing side of a battle, selling himself to escape poverty, burdensome debt, birth in a slave family, or kidnapping. While many slaves did perform agricultural labor and other domestic chores, a number of slaves also served as stewards, craftsmen, and physicians. In Athens, the police force was comprised of enslaved Scythian archers who were empowered to arrest freemen. As the case of the archers demonstrates, not all slaves were in private service. The state oftentimes was the largest slaveholder in a society.

In Rome, the success of the legions in battle brought in thousands upon thousands of slaves. Historians estimate that at the height of Roman power for every one freeman there were three or four slaves. The Roman Senate toyed with the idea of requiring slaves to wear a particular style of dress to distinguish them from freeman, but the idea was scrapped once Senators realized that this would show the slaves their great numbers. Under the law, Roman slaves were allowed to earn a peculium, a small amount of money over their keep. For some Roman slaves this amounted to pocket money, while others accumulated enough that they themselves became slave owners while still in bondage.

Towards the end of the imperial era and beyond, the impecunious freeman and slave saw their lives merge into serfdom where they were permanently bound to the soil. In the Middle Ages, the serfs did not live in a full state of subjection that we associate with slavery. Nonetheless, depending on manorial custom, the limitations imposed were incongruent with what we would recognize as freedom. Full slavery, however, did continue to exist in Europe. Records from William the Conqueror show that in the 1080s, approximately 10 percent of the English people were slaves.

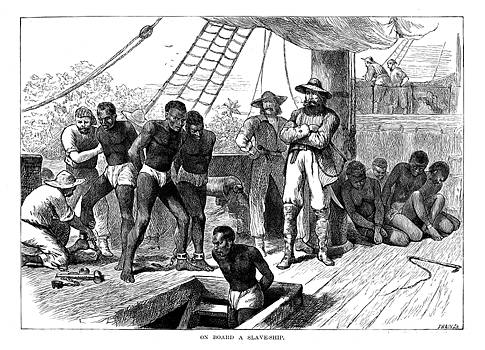

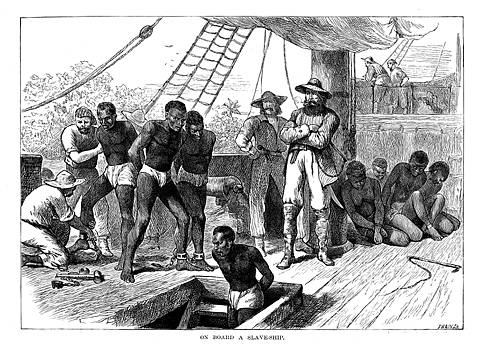

During the Age of Exploration, Africa became a source of slaves for Europe and its colonies in the New World. As Meltzer has observed, “Africans had long known domestic slavery and had traded slaves internally before the Europeans came to their continent.” Although some European slavers made coastal raids and captured Africans, the lion’s share of African slaves were supplied by other Africans through wars of conquest. African leaders allowed Europeans to build costal trading posts to further this commerce. Both sides went into the business relations with open eyes. According to Meltzer:

Each side had goods that the other wanted. Each side knew human bondage. The medieval Europeans sold slaves even of their own faith or nation, as did the Africans. Neither continent was a stranger to the slave trade. Both sides had long accepted it, and both sides joined in practicing it.[4]

Slavery thrived in the Americas with the plantation system, but the institution was not alien to the native inhabitants. The Maya and Aztecs both practiced slavery. Much like the situation in ancient world discussed above, an Indian could be enslaved through wars of conquest, to escape poverty, or for committing certain crimes. In addition to agriculture and domestic service, Mesoamerican slaves were often used as human sacrifices in religious ceremonies.

In North America, slavery was common among the Indians of the northwest coast. Owning slaves was a way for the great chiefs and prominent families to display their wealth. The type of slavery practiced in the region could not be confused with serfdom. The master had full power over a slave’s life. In potlatch ceremonies, wealthy Indians often displayed their riches by expending assets, including the killing of slaves in front of the gathering. Scholars estimate that between five and 30 percent of Indians living in this area were held in bondage.

The tribes of the eastern woodlands also practiced slavery. To prevent runaways, eastern tribes often mutilated the feet of slaves to hinder flight. The eastern tribes used slaves to gather firewood, carry water, and harvest crops.

While Africans were the primary source of slave labor in the United States, we should not forget that some white Europeans continued to be enslaved. For example, during the English Civil War, Cromwell sold a number of royalists into slavery. These supporters of the king were sent to plantations in the Caribbean to toil among the sugarcane. Moreover, indentured servants from across Europe were crammed into boats and sent across the Atlantic where they were sold to the highest bidder for three to six year periods. The conditions on these ships were horrendous—much like those of the Middle Passage–with large numbers dying in route.

These are inconvenient facts for the Grievance Factory. Its power depends upon the assertion that among all the peoples of the world, the United States bears an especial culpability for institution of slavery. This is balderdash. The only thing unique about slavery and the United States is that Union forces resorted to violence and mass bloodshed to abolish the institution. As Thomas DiLorenzo has observed, “[b]y 1861 there was a long history of peaceful abolition throughout the world, including the northern United States.”[5] From 1813 to 1854, peaceful emancipation occurred in Argentina, Colombia, Chile, Central America, Mexico, Bolivia, Uruguay, the French and Danish colonies, Ecuador, Peru, and Venezuela. In the Western Hemisphere, violence predominated in the abolition of slavery only in the United States and Haiti.

Despite what most Americans believe, slavery in the world did not end with the passage of the Thirteenth Amendment in 1865. Slavery still exists in 2020. According to modern anti-slavery advocacy groups, between 21 million to 45 million people are enslaved in the world.[6] This includes forced labor, sex trafficking, and bonded labor where people are compelled to work to expunge debt and are unable to leave until the debt is satisfied. Most of these modern slaves live in India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, China, and Uzbekistan.

If the Grievance Factory truly believed that slavery was such an evil that its effects are still palpable in 21st century America, surely in would bring its power and resources to bear in freeing the wretches toiling in bondage today. In truth, American race hustlers don’t give a farthing about the millions bondsmen laboring throughout the world. They only care about leveraging power and extracting benefits from a people who believe that the United States is unique among the countries of the world for the institution of slavery.

The true evil of slavery is the largely unchecked dominion a master exerts over his bondman. Such unlimited power brings out the worst in fallen creatures. But it is exactly this type of untrammeled power that Leftist elites, thought a false guilt, want to enjoy over the thoughts and deeds of the rest of us.

[1] David Blight, “What is the Legacy of American Slavery?” https://www.cic.edu/p/legacies-of-slavery/Documents/CIC-Legacies-of-American-Slavery-Essay.pdf (last accessed 9/20/2020)

[2] Pesta quoted in Katie Hardiman, “Most college students think America invented slavery, professor finds” https://www.thecollegefix.com/college-students-think-america-invented-slavery-professor-finds (last accessed 9/20/2020)

[3] Milton Meltzer, Vol I, Slavery: A World History 1 (DeCapo Press, 1993).

[4] Id. Vol II, 23.

[5] Thomas J. DiLorenzo, “The Great Centralizer: Abraham Lincoln and the War Between the States,” 3 Independent Review 243, 252 (1998).

[6] http://www.endslaverynow.org/learn/slavery-today#:~:text=There%20are%20an%20estimated%2021,is%20slavery%20at%20its%20core.