To begin with, it is hornbook law* that the signatories to any contract or compact, are all accorded the same rights; that is, no signatory of such an agreement has more—or fewer—rights than any other signatory. Neither does this fact have to be stated in the document; it is understood. If the Party of the First Part is permitted to do or have something as the result of signing, so do all the other signatories whether or not they have demanded that right.

Second, the United States Constitution is just such a compact or contract. Those former colonies—now defined as “sovereign states”—were no different in their condition as signatories than any ordinary person or persons who had signed documents of far lesser importance. The numbers and the matters involved did not in any way affect the acceptable legal presumptions. True, those who signed the Constitution were representing their states, each of which had determined in convention to ratify the document. Thus, each state must be considered a signatory and therefore, bestowed with all of the rights and benefits accruing to every other signatory state.

For many years, Americans have been taught that the Constitution was enthusiastically embraced by all thirteen former colonies when it was determined that the Articles of Confederation did not operate sufficiently for the good functioning of such a diverse group. The Articles, the second attempt at a working relationship among the thirteen disparate entities—the first were the Articles of Association—were written in 1776-77 and adopted by Congress on November 15, 1777. They were not fully ratified by all the states until March 1, 1781. Because of the experience of the former colonists with the overbearing British central authority, the drafters of the Articles deliberately avoided a strong central government by establishing a confederation of sovereign states.

On paper, the Congress had the power to regulate foreign affairs—including the waging of war—regulate the postal service, appoint military officers, control Indian affairs, borrow money, determine the value of coinage and issue bills of credit. In reality, however, the Articles did not give to the Congress the power to enforce its requests on the states for money or troops and by the end of 1786, governmental effectiveness had broken down. And so, a convention was called to “fix” the Articles.

However, it is probable that there were those who believed that the Articles should be replaced by a plan that would settle, once and for all, those matters proving so difficult for the integrated movement into the future of the newly liberated States. One of the things that was determined to be problematic in the Articles was the phrase referring to a “perpetual union.” On June 12, 1776, the Second Continental Congress approved the drafting of the Articles, following a similar approval to draft the Declaration of Independence on June 11. The purpose of the Articles was not only to define the relationship among the new States but also to stipulate the permanent nature of the new union. Accordingly, Article XIII states that the Union being created “shall be perpetual.”

Now, this was somewhat problematic to many of those involved in trying to move the new group of States past its revolutionary birth process. Who knows, but by 1787 when the convention was called to amend the Articles, perhaps the fear by many former colonists of centralized power had somewhat lessened and those involved could see that things would cease to progress with ease and success unless there was a better means of governance than that provided by the Articles—even amended.

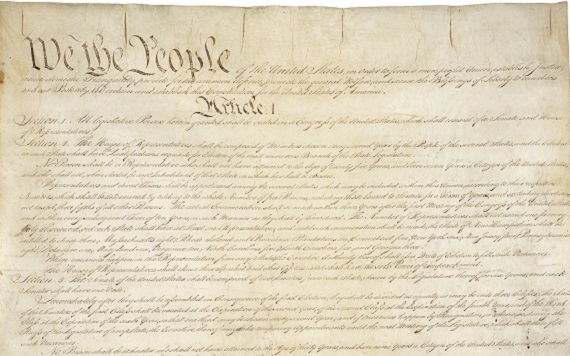

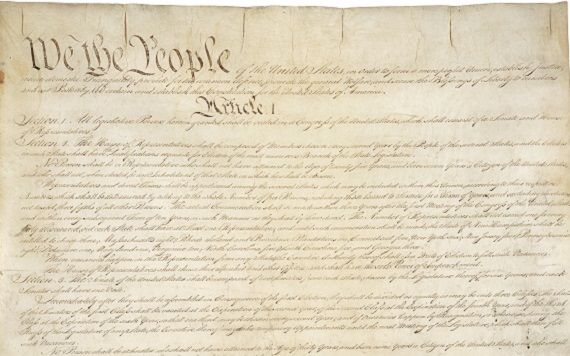

But whatever the reasons involved, in the resultant Constitution, there was no mention of a “perpetual union,” and at no place in that document is the word “nation” to be found. Indeed, in many of the original documents pertaining to the Constitution, in the words “united States” a term that signified the change from the old Articles to new the Constitution, the “u” in “united” is not capitalized! This is significant for had it been capitalized, it could be supposed that the Constitution, by bestowing a title rather than a description with the use of the capital letter in the word “United,” had created an “entity” other than the original thirteen separate and sovereign States. But the words united States as they sometimes appear in that document and others pertaining to it, simply identified the condition of those States; that is, united in their ongoing efforts to function as a “confederation” and not as a nation or a national entity.

However, it is interesting to note that in most of the images of the Constitution, the “u” in “united” has been capitalized and so perpetuates the concept of the creation of just such a “nation” or “perpetual union” as claimed by Lincoln in 1860, and through that claim, his further claim that the “federal” government established by the Constitution was, in fact, a national government free of the restrictions placed upon it by that same Constitution. The best definition of this different understanding of the situation was voiced by Southern historian Shelby Foote who pointed out that after the “Civil War,” the concept of the Republic went from “the united States are,” to “ the United States is,” thus indicating the loss of sovereignty of all of the States of the union and not just the States of the defeated South.

Nonetheless, as noted, the new Constitution was not embraced wholeheartedly by all of those sovereign States involved in its creation. Indeed, there were many who saw the shadow of an all-powerful central government lurking in its words despite every effort to prevent that eventuality. The great Virginia patriot, Patrick Henry, was having none of it. In 1787, Henry had received an invitation to participate in the convention to revise the Articles, but refused to attend as he feared that the convention was a plot by the powerful forces involved to construct a strong central government of which those forces would be the masters.

When the new Constitution was sent to Virginia for ratification in 1788, Henry was one of its most outspoken critics. He wondered aloud why it did not include a list of the rights of the People. Indeed, he believed that its absence was part of the suspected attempt by powerful forces to amass influence at the expense of the People. The arguments of Henry and other Anti-Federalist Virginians compelled James Madison, the leader of the Virginia Federalists to promise the addition of a bill of rights to the Constitution once that document had been approved.

After every consideration had been addressed and after much wrangling, the document was finished with the addition of its first ten amendments also known as the Bill of Rights. One of the things that was easily discovered as the Constitution took shape was that it was impossible to include within it everything that was permissible under it. That being the case, it was determined that the best thing to do was to declare what was not permissible, much as the Ten Commandments are mostly a list of “Thou shalt NOTS!” As a result, the accepted understanding was that if the Constitution said nothing about some subjects—such as slavery and secession—it followed the old legal construct that “silence means assent.” Hence, no argument could be made in the 1850s that slavery was “unconstitutional” because the Constitution said nothing about it and many States even in the North practiced the “peculiar institution” under its benign neglect.

Nonetheless, when the States brought back their ratification documents in preparation for adopting this new form of governance, three States decided that they could not do so without putting a caveat into their documents permitting them to leave the new union if their people determined that it was no longer to their benefit to remain. The terms used in these documents were “resume” or “reassume”—that is, that these States would resume or reassume those powers given up to the “federal” authority under the Constitution and, as a result, remove themselves from the union formed by it. For certainly, such States could not be a part of the union if they were no longer bound by the same strictures as those States that remained. As one scholar put it later, whereas the States acceded to the Constitution by signing it, they could also secede by resuming their former powers and leaving the compact—and the union it created.

Now the three States who provided themselves with this “escape clause” should such in future be needed, were New York, Rhode Island and Patrick Henry’s Virginia. It is possible that it was Henry who was able to prevail upon his fellow Virginians to create the means of an escape from a powerful central government should the need arise.

The ratification documents of New York read (in part) thusly:

We, the delegates of the people of the state of New York, duly elected and met in Convention, having maturely considered the Constitution for the United States of America, agreed to on the 17th day of September, in the year 1787, by the Convention then assembled at Philadelphia, in the commonwealth of Pennsylvania, and having also seriously and deliberately considered the present situation of the United States, — Do declare and make known, —

That the enjoyment of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness, are essential rights, which every government ought to respect and preserve.

That the powers of government may be reassumed by the people whensoever it shall become necessary to their happiness; that every power, jurisdiction, and right, which is not by the said Constitution clearly delegated to the Congress of the United States, or the departments of the government thereof, remains to the people of the several states, or to their respective state governments, to whom they may have granted the same; and that those clauses in the said Constitution, which declare that Congress shall not have or exercise certain powers, do not imply that Congress is entitled to any powers not given by the said Constitution; but such clauses are to be construed either as exceptions to certain specified powers, or as inserted merely for greater caution.

Here the significant phrase is: That the powers of government may be REASSUMED by the people whensoever it shall become necessary to their happiness;

The documents of Rhode Island read (in part):

We, the delegates of the people of the state of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations, duly elected and met in Convention, having maturely considered the Constitution for the United States of America, agreed to on the seventeenth day of September, in the year one thousand seven hundred and eighty-seven, by the Convention then assembled at Philadelphia, in the commonwealth of Pennsylvania, and having also seriously and deliberately considered the present situation of this state, do declare and make known,—

III. That the powers of government may be reassumed by the people whensoever it shall become necessary to their happiness. That the rights of the states respectively to nominate and appoint all state officers, and every other power, jurisdiction, and right, which is not by the said Constitution clearly delegated to the Congress of the United States, or to the departments of government thereof, remain to the people of the several states, or their respective state governments, to whom they may have granted the same; and that those clauses in the Constitution which declare that Congress shall not have or exercise certain powers, do not imply that Congress is entitled to any powers not given by the said Constitution; but such clauses are to be construed as exceptions to certain specified powers, or as inserted merely for greater caution.

Here, the significant phrase is: That the powers of government may be reassumed by the people whensoever it shall become necessary to their happiness.

Virginia presents a slightly more erudite and formal approach, but the meaning is the same. The Old Dominion’s document reads (in part):

WE the Delegates of the people of Virginia, duly elected in pursuance of a recommendation from the General Assembly, and now met in Convention, having fully and freely investigated and discussed the proceedings of the Federal Convention, and being prepared as well as the most mature deliberation hath enabled us, to decide thereon, DO in the name and in behalf of the people of Virginia, declare and make known that the powers granted under the Constitution, being derived from the people of the United States may be resumed by them whensoever the same shall be perverted to their injury or oppression, and that every power not granted thereby remains with them and at their will: that therefore no right of any denomination, can be cancelled, abridged, restrained or modified, by the Congress, by the Senate or House of Representatives acting in any capacity, by the President or any department or officer of the United States, except in those instances in which power is given by the Constitution for those purposes: and that among other essential rights, the liberty of conscience and of the press cannot be cancelled, abridged, restrained or modified by any authority of the United States.

Here, the significant phrase is: DO in the name and in behalf of the people of Virginia, declare and make known that the powers granted under the Constitution, being derived from the people of the United States may be RESUMED by them whensoever the same shall be perverted to their injury or oppression, and that every power not granted thereby remains with them and at their will:

And so, when the Constitution was ratified by the sovereign States, three of those States had put secession caveats in their ratification documents! Those documents were accepted by the other States without demur with regard to those caveats. In other words, the other States accepted the concept of secession at the ratification of the Constitution even though their own ratification documents did not include that caveat.

Why is that a “given?” Because, as before noted, no signatory of any compact or contract has more or fewer rights than every other signatory. If New York, Rhode Island and Virginia could secede from the union created by the Constitution, so could every other signatory State! It was not necessary to put secession into the Constitution any more than it was necessary to put slavery into the Constitution or a host of other everyday acts lawfully performed by the States and their citizens. When someone asked during the crisis in 1860 why the Constitution did not forbid secession, the response was that had it done so, it would never have been ratified!

[*hornbook law: [n] Legal language defining a fundamental and well accepted principle in law that does not require any further explanation, since a “hornbook” is a primer of basics in law.]

The period reference to “the united States are versus the United States is” is found in Thoreau’s Walden.

If you think your enemy cares about rule of law, you are mistaken. You only need to witness the support for Ukraine separating from the Soviet Union (weakening the Soviet Union and its control on Soviet oil) in 1990 and disallowing the Russian-speaking minority to separate from Ukraine (strengthening Russia and its control on Russian oil) in 2014.

It’s all about money. IF the northern States wished to end slavery, they could have purchased the slaves at 3/5ths of their value (after all, a slave is only 3/5ths of a human) from the Confederate States…and if the war had been over slavery, perhaps this compromise could have been suggested. As it was, the Corwin Amendment proved without doubt the war was not over slavery…slavery being the current buzzword for the ignorant. The war was over money, taxation without representation or more correctly, taxation without hesitation…slaves being the 19th century equivalent of tobacco, taxing the owners of such profit-generating equipment was justified to end the power of the masters from the Slave States’ over the federal government. And these taxes, were what the Southern States rebelled over.

It’s always about the money.

Thank you for your efforts to educate.

Rutherford, in ‘Lex Rex’ notes that “Those who have power to make have power to unmake kings.” As Article VII clearly demonstrates, the Union was created by the act of sovereign States, each acting independently of all other agents. Yes, secession is fundamental to REAL American government. Thanks for a very positive and educated review of this subject.