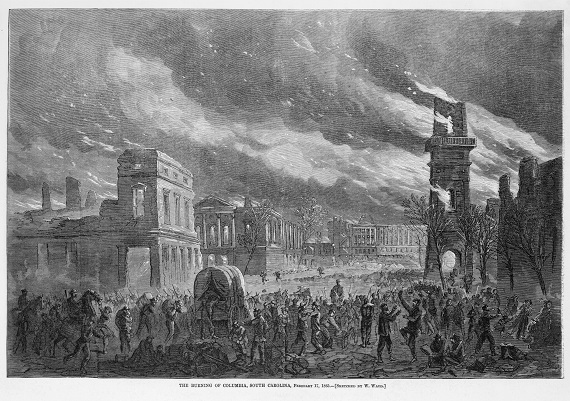

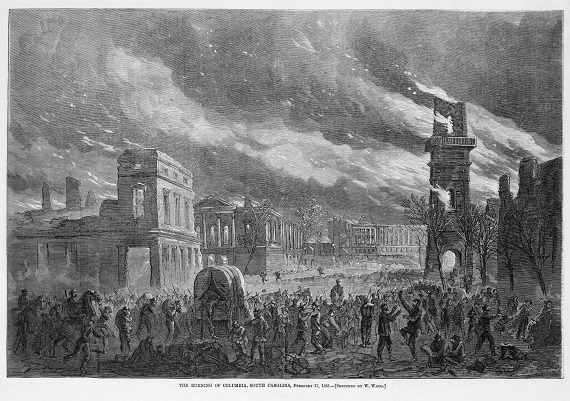

January 2015 ushers in the last year of the sesquicentennial of the War for Southern Independence. One hundred and fifty years ago, the first month of 1865 was the beginning of a cruel and catastrophic winter for the state of South Carolina. Having completed his destructive march through Georgia, General William T. Sherman took possession of the coastal city of Savannah in that state in December 1864. He then turned his eyes toward his next objective, South Carolina. In his report concerning the fall of Savannah, Sherman informed General Ulysses S. Grant that he intended to “smash South Carolina—all to pieces.” His strategy was to divide and confuse Confederate forces by marching on the capital city of the state, Columbia, and destroying as many railroad lines en route as possible. His strategy was also to break the morale of South Carolinians and the Confederate Army.

Sherman’s army numbered a little over 60,000 troops. In January 1865, many of them gathered in the area of Beaufort, South Carolina, a town on Port Royal Island which had been occupied by Federal forces since its capture in November 1861. The white soldiers of Sherman’s army manifested much hostility toward the many black people who lived there, robbing them, destroying their property, and taunting them with racial slurs, and General O. O. Howard, Sherman’s second in command, wrote to another general that his soldiers were “abusing their women.” There were also violent confrontations between white soldiers and the U.S. Colored Troops at Beaufort. Sherman’s men took the lives of at least two black men and injured several others before they departed on their march across South Carolina.

On January 4, 1865, a Charleston newspaper reprinted part of an editorial that appeared in a northern publication, The Philadelphia Inquirer. The article cheered on Sherman’s soldiers as they prepared to embark on their South Carolina campaign, calling South Carolina “that accursed hotbed of treason.” In his excellent book on Sherman, Merchant of Terror, John B. Walters commented on this: “This was a strange hatred which directed its venom not against armies but against the non-combatants of South Carolina and their personal property. The people of the North were, in effect, issuing an open invitation to the Union army to sack and pillage the country.” While he was in Savannah, General Sherman told some ladies there that he had received letters from the “good, church going people of the North” telling him not to leave a house standing in South Carolina.

The “strange hatred” noted by John B. Walters, and carried out through massive destruction and pillage in South Carolina, was partly the result of many years of denunciation of the South by her enemies in the North. For decades before the war, and especially during the conflict, the South was often demonized by Northern abolitionists and radicals, whose ranks included clergymen, newspaper editors, and politicians (some of high office). After the war began, many of them called for harsh measures against the “rebels.”

When the famous English author Anthony Trollope visited America in 1861, he made it a point to hear a speech by Wendell Phillips, a Boston abolitionist and orator who was urging the U.S. government to emancipate the slaves immediately in the hope that they would rise up against the Confederate people. Trollope said of Phillips’ speech, “To me it seemed that the doctrine he preached was one of rapine, bloodshed, and social destruction. He would call upon the government…to enfranchise the slaves at once—now during the war—so that the Southern power might be destroyed by a concurrence of misfortunes…I have sometimes thought that there is no being so venomous, so blood-thirsty, as a professed philanthropist.”

A literal example of “demonization” could be found in products printed by the well-known New York publisher Charles Magnus. During the war, his company produced a series of illustrated envelopes depicting on one side an angel floating beside the United States flag, and on the other, the seal of a Southern state surmounted by a devil. The message was obvious. (Some of these envelopes are found in the library of the Winterthur Museum and can be viewed online in its digital collection of Charles Magnus imprints.)

After the war, Major George W. Nichols, an aide-de-camp to General Sherman, published a book about his wartime experiences which revealed his contempt for the people of South Carolina, whom he dehumanized as “the scum, the lower dregs of civilization. They are not Americans; they are merely South Carolinians.” Nichols thought that the thievery committed against civilians (usually women and old men) by his soldiers was amusing. After describing how the soldiers would search out valuables that had been hidden away by civilians, he added, “These searches made one of the pleasant excitements of our march.”

Halfway through the march in South Carolina, one of Sherman’s officers, Major James A. Connolly, wrote home to his wife that he was “perfectly sickened by the frightful devastation our army was spreading on every hand.” He described the army’s actions as “absolutely terrible” and reported how most houses were first plundered and then burned, and women, children and old men were turned out into the “mud and rain.” He told his wife that he knew the campaign against South Carolina would be a terrible one before it began, but he had no idea “how frightful the reality would be.”

In his book When in the Course of Human Events, Charles Adams argued that the bloodthirsty, even genocidal rhetoric of Northern radicals “found expression in the devastation of civilians and civilian property by Sherman, Grant and Sheridan.” Some of those in power in the North justified their ruthless conduct of the war in part by the supposed wickedness of the enemy, and that ruthlessness was perhaps nowhere more cruelly demonstrated than in Sherman’s campaign through the Carolinas.