If you listen to the modern historical profession, Southern secession in 1861 represented “treason.” David Blight, Professor History at Yale University, has made this belief the part of the core of his attack on Confederate symbols. If we should not take them down because they represent “white supremacy,” then they should be removed because Southerners were “traitors.”

Traitors to whom or what?

Certainly this was an open question in 1860 and 1861. Secession–political, economic, social–had been advanced by various groups since the founding. The very act of independence in 1776 was an act of secession. Secession had been an American principle and an American tale for generations.

It was not until the War that secession became synonymous with treason and even that was the extreme Northern position. The majority of Americans thought otherwise. How do we know this? Clearly the vast majority of the South believed that secession was legal and justified. The several State secession conventions elected to leave the Union by crushing majorities. Nearly seventy-five percent of the Southern white male population fought for independence (secession) and their enthusiasm was only trumped by Southern women who would shame the men into joining the cause.

As for the North, the Lincoln administration faced constant opposition from the opening shots of the War, and he received only fifty-five percent of the NORTHERN popular vote in 1864. His opponent, George McClellan, ran on a moderate peace platform and probably would have opened negotiation had he won the election. If you add the large minority vote in the North to the crushing support for secession in the South, the majority of American believed the Confederate States not only had de facto but also de jure independence from 1861-1865. In other words, secession happened and it was not treason. The Southern States were independent and no longer bound by the language of the United States Constitution.

There were Northerners after the War who rushed to prosecute Southerners for treason. Only one, Henry Wirz, had his neck stretched, but that was not for treason. Every Confederate leader avoided being convicted of the charge, including Jefferson Davis. Thousands were charged with treason and faced trial in kangaroo courts as the Union army occupied the South. Union partisans in East Tennessee were particularly aggressive, but again, even where these Republican led courts found men guilty of treason, the verdicts were quickly overturned in higher courts.

Post-bellum secession took various forms until the modern era, from advocacy for regionalism, to the creation of semi-autonomous communities like the Tuskegee model advanced by Booker T. Washington. These were acts designed to embrace the American concepts of legitimacy, consent of the governed, and self-determination and were opposed to monolithic nationalism. It wasn’t until the early 1990s that political secession was back on the table due in large part to the increasingly unresponsive and oppressive national centralized structure entrenched by twentieth century progressives.

The one Supreme Court decision that somewhat addressed the issue of secession, Texas v. White in 1869, never classified the act of secession as treason. This makes the modern insistence that secession equated treason somewhat bizarre. It exemplifies the lack of understanding the establishment historical profession has for the original Constitution and exposes the “noble dream” of objectivity. These historians, like Blight, are biased toward the extreme Northern position of the immediate post-bellum America, a position that the majority of Americans rejected. The modern historical politically motivated objection to secession is not to facts but to interpretation.

The fact remains that the charge of “treason” has never been comprehensively accepted by the American public, even to this day. See General Kelly’s statements to Laura Ingraham. The case for Confederate monuments and symbols thus becomes more pressing. Should antebellum Southerners be cast as treasonous villains in a larger Northern righteous cause mythological drama, the American principles of self-determination and consent of the governed quickly fade into oblivion. You aren’t free if you can’t leave. The founding generation North and South believed this, as did most Americans until 1861.

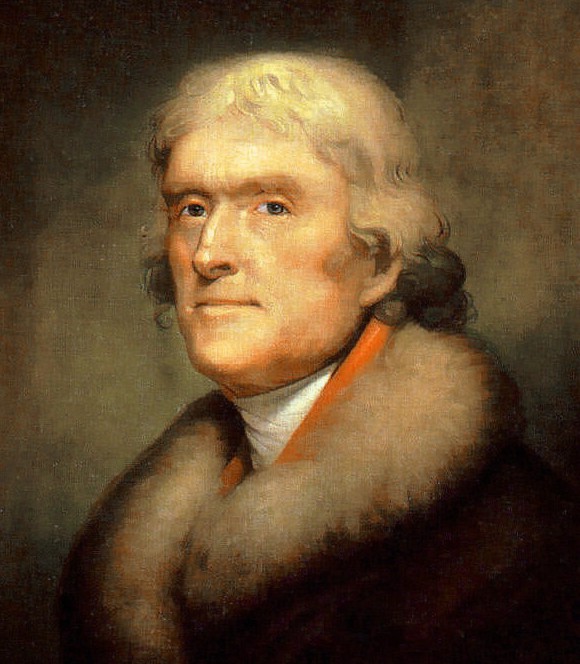

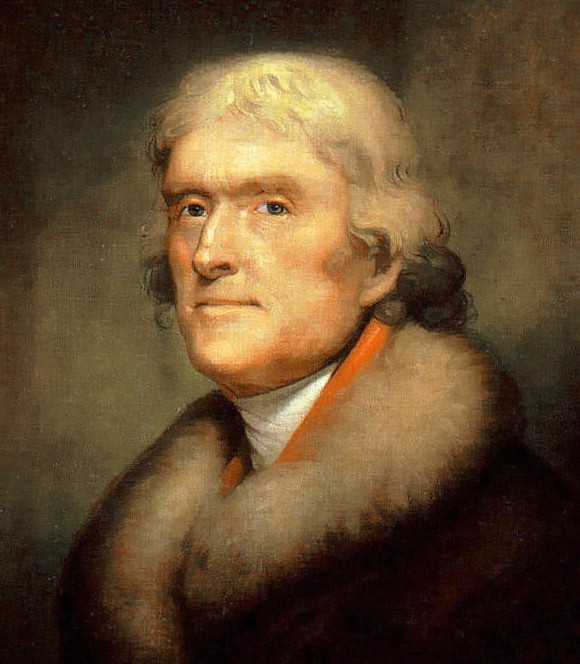

Confederate monuments and symbols represent the American political soul, not of “white supremacy,” but of what William B. Travis called “the American character” in his letter from the Alamo in 1836 or what Thomas Jefferson labeled a “right” and a “duty” in the Declaration, namely to “alter or to abolish” government that does not protect life, liberty, or the pursuit of happiness. We can argue whether secession was justified in 1861–a minority of Southerners did just that (many were large slaveholders)–or if secession is a preferred course of action today, but we should never call it “treason.” That is un-American.