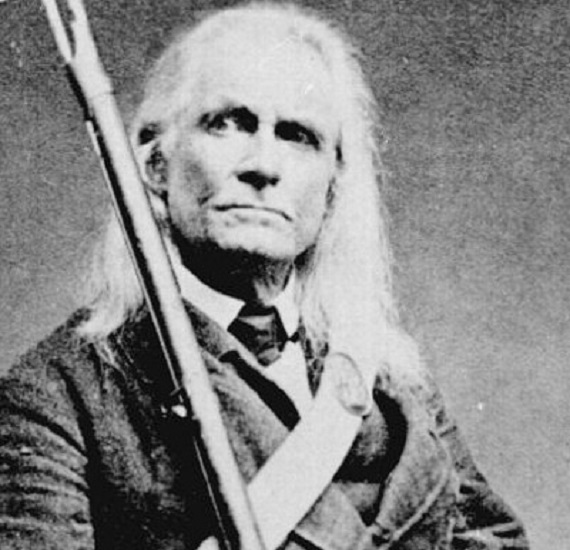

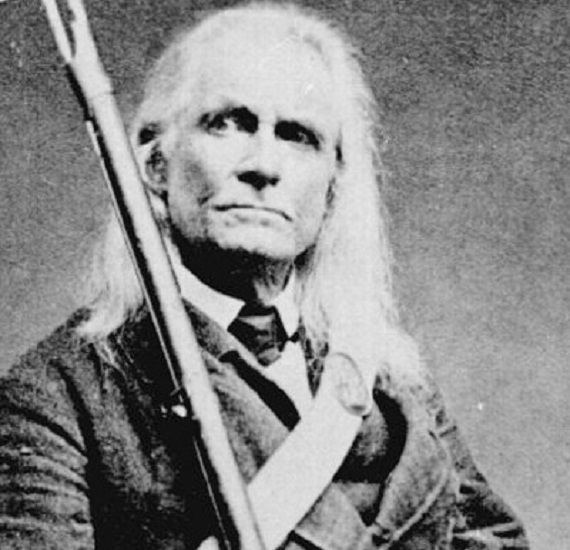

Edmund Ruffin, the consummate Fire-Eater, was far greater than the sum of his parts; as Avery Craven, the finest of his biographers, expressed, “as the greatest agriculturist in a rural civilization; one of the first and most intense Southern nationalists; and the man who fired the first gun at Sumter and ended his own life in grief when the civilization that had produced him perished on the field of battle, his story becomes to a striking degree that of the rise and fall of the Old South.” Gentleman, planter, radical, and warrior, the life and death of Edmund Ruffin is indeed that of the nation that he poured his life’s labors into creating. As Craven continued, “The Old South that rose to completion in what are called antebellum days held no figure that better expressed her more pronounced temper and ways than did this Virginian.”

Of high birth into a venerable family, the aristocratic Ruffin ended his honeymoon early to enlist as a private in the first volunteers’ regiment called out from Virginia during the War of 1812. Though the young man saw no combat in his six months of service, the Virginian relished the military discipline which had been instilled within him, seeing, as most of our finest men once did, military service as equal parts duty and responsibility, the highest manifestation of the noblesse oblige which once suffused the American ruling class. He elaborated on this principle, writing that “young people of ‘gentle birth,’ or used to early comforts, but also of well-ordered minds, could undergo necessary hardships with more contentment and cheerfulness than other persons of lower origin, and less accustomed to the indulgences and the training that wealth and high position afforded.”

Ruffin returned home to find the great farmlands of Tidewater Virginia ruined, its fields fallowed not only by rampaging British soldiers, but by generations of careless agriculture. Knowing next to nothing of the arts of farming, he looked to his neighbors for assistance, only to discover that it was an exercise in futility; his neighbors “adhered blindly to traditional, ineffective methods.” Determined, he followed the instructions of John Taylor’s Arator series to the letter, which only served to deepen his soil erosion. Equally as ignorant of chemistry, Ruffin was nevertheless intrigued by Sir Humphry Davy’s Elements of Agricultural Chemistry, which speculated that carbonate of lime might neutralize soil acidity. Working from engravings in Davy’s book, Ruffin reproduced the author’s testing apparatus and used his new equipment to test the chemical composition of he and his neighbors’ soil.

As Eric Walther explains, Ruffin’s tests “showed that the fossil shells, or marl, so abundant in the region had sufficient alkalinity to correct the chemical imbalance in the fields.” In early 1818, Ruffin excavated marl from pits on his estate; though Tidewater farmers had used marl before, Ruffin was the first to combine marling with John Taylor’s methods of cultivation. His gambit worked wonders, producing a corn yield forty percent greater than his control sample. Walther thus remarks, “The self-trained scientist had proved skeptical neighbors wrong and discovered the key to rejuvenating the soil of the Tidewater South.” In order to popularize his scientific agriculture, Ruffin launched a monthly periodical, the Farmer’s Register, in 1833. This entry into publishing awakened something within the brilliant planter.

By the early 1820s, the Virginian believed that the Federal government, though it had not yet become the Leviathan that it was in short order to become, had usurped too much power; Ruffin feared , quite presciently, that his “States’ Rights republican creed and principles will hereafter, as heretofore, be professed only by parties out of power and seeking its attainment.” He possessed “very little respect for the general course and measures of any party” and therefore belonged to none; in 1823, Ruffin rejected all five of the likely candidates for the 1824 Presidential campaign, seeing Andrew Jackson, Henry Clay, John Quincy Adams, John C. Calhoun, and William H. Crawford all to a man as having “disregarded constitutional checks on Federal power through their advocacy of tariffs, internal improvements, and Federal banks.” Ruffin urged his fellow Virginians to support Nathaniel Macon, and, as a last resort, promoted the hated Federalist John Marshall; as Ruffin saw it, he would prefer an avowed, consistent Federalist to a Federalist who called himself a republican.

To agitate for a States’ Rights republican party that would advocate “strict limitation on Federal powers,” Ruffin and his son, Julian, established the Southern Magazine and Monthly Review in 1841. Its first issue featured a piece by Ruffin, “Revolution in Disguise,” in which the Virginian deplored “the great changes which have already been made in the spirit and working of the Constitution, without touching its letter.” One specific target of his ire was the establishment of protective tariffs, which functioned to facilitate vast transfers of wealth from the mighty agrarian South to the fledgling industrial North. Ruffin also observed, with increasing alarm, the drive, then already well on its way, to institute mass democracy; he held “fellows of the baser sort” in contempt, seeing that popular democracy would forever eviscerate the republic which had been bequeathed us.

Ruffin felt an instinctive distaste for his fellow Virginian, Thomas Jefferson. As Craven explained, “he saw the harm that the words of the Declaration of Independence were doing in the mouths of ‘anti-slavery fanatics’ and boldly proclaimed that the assertion that ‘all men are born free and equal’ was ‘both false and foolish.’ No man had ever been born free, and no two men ever born equal.” Moreover, Ruffin was well aware that from Jefferson had come those “corrupting and poisonous” political theories “of democratic perfection” which had “caused more evil and done more to destroy free and sound institutions and to upset all that was stable and valuable in our government than all…the real and avowed opposers of popular rights could have effected if their power had equaled their wishes, or than all…demagogues could have effected in practice, if they had not been given strength and power by constitutions founded on universal suffrage and equality of the people in theory, but truly the supremacy of the lowest and basest class led and directed by baser and mercenary demagogues, seeking exclusively their own selfish benefits.”

“There is no greater fallacy,” Ruffin continued, “than the supposition…that men will generally be directed in their choice of representatives…by consideration of superior competency and trustworthiness of the persons voted for.” Universal suffrage was a snare and a delusion; only those with “property to guard, and much more of education, ability, and virtue than the general mass” could responsibly exercise the franchise. A government based upon the inherently flawed notion of universal suffrage, a government, as the tyrant Abraham Lincoln would later conjure, “of the people, by the people, and for the people,” Ruffin wrote, “will be a government of and by the worst of the people.”

Soon, Ruffin turned to the issue of banking reform, launching another periodical, the Bank Reformer. Though he abandoned the publication in 1842, he continued to rage against the corrupt financial system; instead of endorsing banknotes with his signature, he started inscribing various diatribes on them, first by hand and then by a small press bought just for the occasion, and placing them back into circulation, so that each note might “instruct by its back as many persons as it cheats by its face.” Courtesy of the budding radical, Virginians could read attacks such as the following on their money: “The paper banking system is essentially and necessarily fraudulent. The very issue of paper as money is always a fraud; and must operate to rob the earnings of labor and industry, for the gain of stock-jobbing, wild speculation, and knavery.”; “The promise on the face of this note is FALSE; and the issue of such notes is both a banking and a government FRAUD, committed on the right and interest of labor and honestly acquired capital.”; and, “The object, as well as the effect, of the paper-money system is to enable those who have earned or accumulated nothing by labor, to exchange this nothing for the something, and often the everything earned by the labor of others.”

As sectional tensions heated to the boiling point, Ruffin hardened in his politics, embracing Southern nationalism and, after the Nashville Convention led directly to the Compromise of 1850, “a grievous wrong and humiliation of the South,” completed his transformation into the most volcanic Fire-Eater of them all. He pseudonymously wrote a series of articles for the Richmond Examiner and the Charleston Mercury, calling for Southern resistance to Yankee depredation. He urged Carolinians, then the most Southern of the Southern people, to lead the way “in this holy war of defense of all that is worth preserving to the South.” In 1851, Ruffin stepped into the open, initiating a phase of public activism to rouse the people of the South from their slumber into the glorious future that only secession could achieve. At long last, the Virginian was catapulted from Outer Darkness to a household name, devoting the next decade of his life to preaching the evangel of disunion with a network of other Fire-Eaters. Ruffin proposed one thing, and one thing only: “TO SUBMIT NO LONGER.”

True men, the Fire-Eater argued, must refuse to be “continually insulted and derided by Northern politicians and Northern publications, as braggarts and boasters who will not dare to defend what we claim to be our rights.” Southrons must dissolve the “Union” with the “so-called Northern brethren — actual enemies and depredators!” It was the abolitionists and their Northern coalition of the damned who were “the true and only disunionists.” They had always been the aggressors, the South their passive whipping-post. Southern independence, Ruffin thundered, was the sole alternative to “degradation and final prostration…to glut the appetite for power and prey of the Northern political abolition party.” He was, as ever, correct; though it is often said that the Fire-Eaters “fomented” secession, as if they were merely a band of crazed psychopaths hell-bent on murder and mayhem, nothing could be further from the truth. The South, its champion Edmund Ruffin included, did not agitate or foment secession, but was rather forced into secession, its back against the wall with no recourse left for its self-preservation. Secession was survival.

With the Kansas-Nebraska Act and the rise of the Republican Party, Ruffin found the ground grew ever-more fertile for the proposition of a Southern Confederacy. As he noted, “I was surprised to find how many concurred with me, in the general proposition, though scarcely one of them would have dared to utter the opinions, at first, and as openly as I did.” He found that, in Walther’s words, “only the rise of the Republican Party had convinced other Southerners that perpetuation of the Union posed a real threat to their liberties, interests, and very existence. Ruffin had spent his entire life trying to save the South by rehabilitating its agriculture and defending its rights. But now, Ruffin discovered his ultimate crusade: saving the South itself.” Despite growing evidence that the zeitgeist was shifting, he saw nowhere any evidence that his fellow Southrons were willing to take any meaningful action. He was desperately frustrated by the fact that, as he saw it, “not one in one hundred of those who think with us, will dare to avow their opinions, and to commit themselves by such open action.” He believed that, at least for the time being, no one could “rouse the South.”

The Fire-Eater understood that, with the 1860 election fast approaching, “every man who hopes to gain anything from the continuance of the Union, will be loud and active in shouting for its integrity and permanence.” Privately, he adopted an accelerationist position, hoping for a sectional division of the Democratic Party and the election of a Republican President, “so that the dishonest and timid Southern men may then be as strongly bribed by their selfish views to stand up for the South, as now to stoop and truckle to the North.” It should then come as no surprise that Ruffin was positively thrilled upon receiving the news of the murderer John Brown’s attempted slave insurrection at Harper’s Ferry, Virginia.

Aghast at the Northern canonization of the fiend, Ruffin wrote that it was “astonishing even to me, and also very gratifying to me, that there should be so general an excitement and avowed sympathy among the people of the North for the late atrocious conspiracy.” He thought that surely this act of terrorism “must open the eyes of the people of the South” to the now uncontestable truth that secession was “the only safeguard from the insane hostility of the North to Southern institutions and interests.” The Fire-Eater hurried to “the seat of war” to witness Brown’s execution, in a crowd that included Thomas Jackson, soon before he became our heroic Stonewall. Ruffin hoped that Brown’s execution would be the spark of a sectional conflict that would finally trigger the destruction of the Federal Union. In his diary, he wrote, “For my part, I wish that the abolitionists of the North may attempt a rescue. If it is done, and defeated, every one engaged will be put to death like wolves.” Even if, in his scenario, Brown did manage to escape, Ruffin thought that it would be “a certain cause of separation.”

Upon his arrival in Harper’s Ferry, throngs of young men, many of whom would be lying cold in unmarked graves across the riven Dixieland that they so loved, saluted the Fire-Eater. Ruffin’s heart soared. He persuaded the commander of cadets from the Virginia Military Institute to allow him to join them in the guard detail at the hanging in Charlestown. As he entered their ranks, he saw that the young men had to use “all the constraint of their good manners to hide their merriment.” As the terrorist fell through the scaffolds, a rope around his lifeless neck, Ruffin looked on in solemn reflection — and, not so strangely, respect. Later, he wrote that “it is impossible for me not to respect his thorough devotion to his bad cause, and the undaunted courage with which he has sustained it, through all losses and hazards…The villain whose life has thus been forfeited, possessed but one virtue (if it should be so called,) or one quality that is more highly esteemed by the world than the most rare and perfect virtues. This is physical or animal courage, or the most complete fearlessness of and insensibility to danger and death.”

To keep alive the memory of what Brown and his Yankee handlers had meant to do, and thereby stoke the smoldering fire of Southern nationalism, Ruffin obtained one of the pikes that the murderer and his accomplices had brought to Virginia to arm slaves with. He pasted a label on the pike’s handle: “Samples of the favors designed for us by our Northern brethren.” Before he carried out his plan himself, Ruffin proposed his scheme to the Virginia legislature by way of the Richmond Examiner, writing: “The pikes brought to Harper’s Ferry by John Brown, which were devised and directed by Northern Conspirators, made in Northern Factories, paid for by Northern funds, and designed to slaughter sleeping Southern men and their awakened wives and children, were captured before being used and so diverted from their designed purpose. Still they may be put to another and most effective use, and that for the defense of the people of the South for whose butchery they were designed. It is respectfully recommended to the Legislature of Virginia, to order that one of these weapons shall be formally presented to each of our sister slaveholding States, and sent to their respective Governors, to be placed in the legislative hall, and exposed to the view of every visitor. Each one of these will then serve as a most eloquent and impressive preacher, appealing…to the patriotism of the people, and urging their sure and perfect defense against all assaults from unscrupulous and measureless enmity from Northern Abolitionists. The pikes may serve well…to rouse and encourage them…to battle against their enemies and oppressors.”

Though Virginia did not follow her son’s recommendation, he was undaunted. He carried John Brown’s pike to Washington, showing his artifact to a delegation of Southern Congressmen. The reaction thus generated convinced Ruffin to keep it up, and, after persuading the superintendent of the Harper’s Ferry armory to send them his way, he followed his plan, sending a labeled pike to the Governor of each of the slave States. Ruffin obtained a suit of homespun cloth, manufactured entirely in Virginia, with Virginian material, by Virginians, and wore it as he paraded with pike in hand to promote Southern manufacturing and a boycott of Yankee goods. In 1860, the Fire-Eater wrote Anticipations of the Future, a speculative fiction novel taking the form of a series of extracts from dispatches between an English war correspondent and the London Times, detailing a brutal civil war from 1864 to 1870 upon the ascension of William Seward to the Presidency. Ruffin explained that, in his book, “I suppose every incident of danger, damage, or disaster to the South, which is predicted by Northerners, or Southern submissionists — as war, blockade, invasion, servile insurrection — (which I do not believe in myself,) and supposing these, as premises, I thence follow through what I suppose to be the legitimate consequences,” Southern victory. Writing, even in fantasy, of the annihilation of the Union and the slaughter of Yankee troopers was “amusing to my mind, and…conducive to immediate pleasure.”

His spirits were further invigorated by the sectional schism that killed the national Democratic Party at its Charleston convention, rejoicing “that the South will be henceforth separated from and relieved of the insatiable vampyre, the Northern democracy,” and that the break would hasten the ascension of an abolitionist to the White House and thus serve as the spark for secession. After voting for John Breckinridge, the Southern Democratic candidate, Ruffin set out immediately for South Carolina, the State in closest alignment with his politics, where he hoped that “even my feeble aid may be worth something to forward the secession of the State and consequently of the whole South.” Upon reaching the South Carolina border, he was relieved, vindicated by the “universal secession feeling.”

At his hotel in Columbia, a crowd gathered, calling him to make a speech. He assented: “Fellow-citizens: I have thought and studied upon this question for years. It has literally been the great one idea of my life, the independence of the South, which I verily believe can only be accomplished through the action of South Carolina.” Ruffin urged steadfastness, directing Carolinians to act quickly, both to “give encouragement to the timid” and “frighten your enemies.” A few nights later, in Charleston, another crowd roused him into oratorical action. He obliged, crying, “My friends, brother disunionists!” If Virginia remained in the Union “under the domination of this infamous, low, vulgar tyranny of Black Republicanism,” but any other State did secede, the Virginian vowed, “I will seek my domicil[e] in that State and abandon Virginia forever.” The next morning, he helped to raise the Palmetto Flag on a new, ninety-foot-tall secession pole. That December, the Fire-Eater was again invited to Charleston to sit at a State convention and witness his long-sought dream become reality. He kept one of the pens used to sign the secession ordinance as “a valued memento of the occasion.”

When he learned that Jefferson Davis had been elected President of the Confederate States of America, Ruffin hailed the new administration as having greater “intellectual ability and moral worth” than any since James Madison’s, though he would later write that Davis was “hard-headed and soft-hearted while Lincoln was soft-headed and hard-hearted.” The Virginian resolved to abandon his State before the inauguration of Abraham Lincoln, “to avoid being, as a Virginian, under his government even for an hour.” He determined never to return, except to visit his family, until Virginia left the lie known as the United States. Thirsty for action, Ruffin was pulled, as if by the hand of God, back to Charleston, where he and his destiny finally converged. Convinced that the slightest bloodshed would force the rest of Dixie to come to the aid of Carolina, it was his fervent wish that he would personally draw fire from the Yanks at Fort Sumter as he sailed with local officials to inspect the fortifications around Charleston Harbor.

Just after he had arrived from Virginia, Ruffin had packed his bag, procured a musket from the commander of the Citadel, and hurried to join the young men who were to make his dreams a reality. As the tyrant in the White House plotted to force the South Carolinians to make the first move, or rather to make them appear to have fired the first shot, Ruffin added the insignia of the Palmetto Guards to his homespun suit and joined the Iron Brigade on Morris Island. The commander of Confederate forces in the harbor had designated the Palmetto Guards to fire the first shot of the War for Southern Independence, and the company bestowed their honor upon the elderly Fire-Eater. He was “highly gratified by their compliment, and delighted to perform the service — which I did.”

Craven described it best: “The first gray of an April morning silhouetted Fort Sumter against the eastern sky…On this morning, when the drums at Morris Island had roused the men of Steven’s Iron Battery, an old man of 67 years, his long white locks hanging down upon the shoulders of a homespun coat, had taken his place by the side of the ‘64-pound Columbiad’ that had been selected to fire the first official shot of the fight… As the signal gun flashed, hiss gray eyes answered, and he pulled the lanyard to loose the storm on Sumter, knowing that the object of years of effort was being realized, the repressions of a lifetime lifted, and that a citizen long out of step with the dominant forces in Southern society had caught stride…A man and a newborn nation had sown the wind.” Ruffin’s aim was true, the fort struck, the United States broken, the Old South more swollen with cheer, love, and life than ever it would be again.

President Davis wrote the Fire-Eater personally, generously telling the Southern patriot to “accept my best wishes and grateful acknowledgement of your heroic devotion to the Cause of the South.” A week after the victory in Charleston, Julian Ruffin named his newborn son, Edmund’s grandson, Edmund Sumter Ruffin. This was the same week that his beloved Virginia joined the Confederate States of America, soon to make it its capital; Ruffin could return home, his vow unbroken. Upon his homecoming, he was beside himself over his State’s unpreparedness, and wrote several missives to then-Colonel Robert E. Lee and President Davis, advising them on defensive fortifications and urging them to revoke the military appointments of those poseurs who were recently among “the most thorough and abject submissionists to Northern oppression and to Lincoln and to abolition,” further recommending that all those who carried even the whiff of disloyalty “be either driven out of the C[onfederate] S[tates] or treated as enemies and prisoners.” For good measure, the Fire-Eater demanded that all Northerners currently in Confederate territory be considered enemy combatants unless they gave “full evidence of being Southern in principle and in acts.”

The old man followed the fighting men of Dixie into the fray, his infirmities leading to a sympathetic unit carrying him into battle astraddle one of its cannons. At the opening skirmishes of Manassas, the Fire-Eater came upon a body of straggling Confederates. Enraged, “lifting his gun above his head, he shouted his indignation at their cowardice and pleaded with them to follow him back into the battle. But they would not stir. War to them had become a reality…Ruffin went on alone, determined that his body should be left upon the field when the [Federals] swept southward.” All indeed appeared lost, when suddenly the Yanks were routed; Ruffin fired the first cannon shot at the Suspension Bridge over Cub Run as the Federals jammed themselves up retreating across it, striking with wonderful accuracy. He thus conjured into reality the Yankee blood which his pen had so gleefully spilt in his Anticipations. Initially, he saw only three corpses, two of whom he believed were already wounded or killed before his attack; crestfallen, Ruffin stated that “this was a great disappointment to me. I should have liked not only to have killed the greatest possible number — but also to know, if possible, which I had killed, and to see and count the bodies.” Later, he was relieved to learn that he, by his own hand, had rid the world of six hated Yankees.

As the Fire-Eater learned of ever-increasing reports concerning Federal atrocities, he saw that the Yankees were waging war “on a system of brigandage and outrage of every kind,” that the South was not fighting against “an honorable enemy, carrying on honorable and legitimate warfare,” but rather one so abhorrent that they “should be treated as robbers, incendiaries, and murderers.” Ruffin concluded that blood must be repaid in blood, that every Northern prisoner whom it was not “easy and certain to make prisoner…should be shot,” and that guerrilla warfare under the black flag was all that the Union, now beyond the Pale of civilization, deserved. When the Mayor of Richmond called all men exempt from military service to defend the city, Ruffin enlisted in the company; his total, unerring, wholehearted dedication to the Cause is further illustrated by Craven, who told us that, upon receiving the news that one of his grandsons had been killed in the defense of Richmond, Ruffin, “like the men in the storybooks…only voiced the regret that he did not have more of flesh and blood to give. It was a paltry price to pay for the salvation of the capital of the Confederacy.”

After brutal warfare and Federal incursions in eastern Virginia drove him from his plantations, he returned to scenes of absolute carnage. Craven, using Ruffin’s own descriptions, wrote of the shambles that had been made of Beechwood: “As he entered the fields, he found them stripped of grain and lying bare. The yard of the mansion was scattered over with rubbish — ‘broken chairs and other furniture, broken dishes, plates and other crockery, feathers emptied from the ticks of featherbeds and different other filling materials of mattresses. The doors of the house were all open, and many of the windows broken in, glass or sashes.’ Within the house, conditions were even worse. All the mirrors were either broken or carried off; the rooms were filled with ‘rubbish and litter, produced by the general breakage and destruction of everything that could not be conveniently stolen.’ Every article of furniture, without exception, showed material damage which could only have come from ‘willful and malignant design.’ The library had been frightfully pillaged, several thousand books having been stolen and the doors of the bookcases torn from their hinges. The old harmonicon, which Ruffin loved so much, had yielded up its glass panels; the pictures on the walls were gone or hanging from their frames in ruin; his valuable collection of shells and fossils, gathered on his agricultural expeditions or sent by friends from all over the world, was scattered about or carried away with other small valuables to become souvenirs in Northern homes for years to come. The walls of the mansion were covered with tobacco juice or defaced with names or filthy expressions written in charcoal or excrement.”

Some of the phrases that disgraced Ruffin’s walls: “This house belonged to a Ruffinly son of a bitch”; “You did fire the first gun on Sumter, you traitor son of a bitch”; and, “Old Ruffin, don’t you wish you had left the Southern Confederacy go to Hell (where it will go) and had stayed at home.” Most of them were too filthy to be reproduced. A Pennsylvanian wrote in one of Ruffin’s books, “Owned by Old Ruffin, the basest old traitor rebel in the United States. You old cuss, it is a pity you go unhanged.” But what hurt the Fire-Eater the worst, Craven explained, “was the loss of all his private papers, many having been carried away, the rest torn and scattered about in such a way as to render it impossible to restore his files. Nearly as painful was the wanton girdling of his great oaks, which had no other purpose than to cause their death and to inflict a wound on the very physical South. These were losses which made insignificant the carrying off of all his mules and cattle and all the grain that had been stored for their use. Ruffin estimated his material losses and those of his son at not less than 150,000 dollars [over three million dollars today]. His more vital losses could not be measured.”

His grandson, Thomas, recently paroled from a Yankee prison, wrote him of the condition of Marlbourne, his other plantation: “Every window in the house was broken, all the fences destroyed, the trees cut and burned, the drainage ditches dammed to furnish water for the horses, and everything of value in the house and outside stolen and carried away.” The Fire-Eater’s reaction to the total destruction of his property was equal parts the desire for vengeance and the entrenchment of his singular determination. He called for a sweeping invasion of the North, and, “justified by Yankee examples,” demanded that Southern armies leave “every village and town…in ashes” as they gave the Federals a throatful of their own poison. Ruffin, though his fortune was in ashes, his wealth almost entirely vanished and dwindling fast, contributed all that he could to the relief fund for victims of the Yankee rape of Fredericksburg. The survival of his cherished Southern nation took precedence over all else, overriding even his grief over the death of his son Julian, killed in battle at Drewry’s Bluff in 1864.

In March, 1865, the Virginian sent the Confederate Treasury seven hundred dollars, nearly all of the cash that remained to him, desperately hoping to inspire others to follow his selfless example. Confederate bonds to the tune of 1,150 dollars soon followed, and then the family plate and his gold watch. Ruffin pleaded with his children to “contribute everything that can be spared to defend us from the enemy,” and, Craven noted, the Fire-Eater “avowed his own purpose to retain only enough to prevent dependence on others whose burdens were already too great.” He even urged the Secretary of the Treasury to make taxes “as heavy as our people will bear” for the duration of the War. Though he held out for Confederate triumph until the bitter end, he came to realize that the Southern nation would soon meet its demise. He longed to die with the Cause that had given his life meaning, writing that his death and decomposition “cannot occur too soon.” As Craven wrote, “A man without a country was already dead! If the God of Battles had overlooked one of his tired soldiers on the field, might he not hasten on to join his comrades without further waiting? To be wrapped in a blanket and ‘buried as usually were our brave soldiers who were slain in battle’ was his only wish.”

Craven continued, noting that “when, on April 12, the shattered remnant of Lee’s once-glorious army…passed before the ‘men in blue’ to lay down their arms, the old man sat again and wrote of another April day exactly four years before when the guns had turned on Sumter. He knew that the Confederate States of America had come to the end of its stormy life. He knew also that the Old South of which he had been a part had run its course. The men in tattered gray who were turning their tear-stained faces southward were going back to begin all over again.” The Fire-Eater could foresee “nothing but failure,” writing that “for years back, I have had nothing left to make me desire to have my life extended another day” aside from the Confederacy, for the survival of his Southern brethren and the land that they shared and loved. His hopes were extinguished, Richmond fallen, Dixie surrendered. He believed that his presence endangered the lives of his family, predicting that President Andrew Johnson would order the execution of secessionist Fire-Eaters and Southern leaders. When he discovered that his homespun coat of Virginia cloth had been stolen by Federals, his heart sank to new depths; he had worn the coat at Fort Sumter and Manassas, and “valued [it] as a relic and memorial.”

Reconstruction, Craven remarked, would almost immediately prove that Ruffin’s worst predictions had been prophetic. Before the Black Republicans had finished, “civil rights were to vanish before arbitrary military rule; native leaders were to be thrust aside to make place for grasping ‘carpetbag’ adventurers; the social pyramid was to be upturned and negroes, just out of slavery, given dominance; the whole economic order was to be destroyed because Northern men had never understood the part that the plantation system played in Southern life and thought that slavery made up the whole relationship between the races. The South was to be subjected to an effort to make it over into what the abolitionist group thought it should be. All that had been feared by the most extreme Southern alarmists from the beginning was to be carried out in detail.”

“I am…a helpless and hopeless slave, under the irresistible oppression of the most unscrupulous, vile, and abhorred of rulers,” Ruffin wrote. He would not — could not — face life among freedmen. The Fire-Eater was profoundly disheartened, shocked to his core that his fellow Southrons accepted defeat, humiliation, and the annihilation of their society “so quietly and coolly, as if we were already prepared for, and, in great measure, reconciled to their speedy approach and infliction.” The attitude of his countrymen, Walther notes, “seemed a rebuke to his life’s work. He felt rejected and unappreciated by his countrymen, just as he had before secession.” Unlike other of his fellow Fire-Eaters, though, Ruffin would not seek a pardon, nor would he flee his beloved South. He chose instead to leave his nation a legacy of defiance, a challenge that he so hoped would be taken up by generations then scarcely perceptible silhouettes on a horizon far distant. Edmund Ruffin, 71 years old, resolved to die by his own hand, unwilling to live in a world without the Southern Confederacy.

“Methodically and carefully,” Walther explains, “Ruffin prepared for his death. First, he had to overcome his fears of death and of transgressing against God by committing suicide. He prayed for weeks that God would divert him from his intentions if they were sinful. He also read the Bible, searching for a specific injunction against suicide. He found none. God’s commandment not to murder, Ruffin believed, did not apply to suicide. He reasoned that murder involved taking the life of another, and against his will. Furthermore, Ruffin noted that the Bible included exceptions to the Seventh Commandment by permitting the execution of criminals and of enemies in wartime. He found confirmation…in the story of the Jews who killed themselves at Masada rather than face certain enslavement and death at the hands of the Romans.” The Fire-Eater was ready to perform the ultimate act of secession.

At ten in the morning on Saturday, June 17, 1865, Ruffin wrote his penultimate statement: “I here declare my unmitigated hatred to Yankee rule — to all political, social, and business connection with Yankees — and to the Yankee race. Would that I could impress these sentiments, in their full force, on every living Southerner, and bequeath them to every one yet to be born! May such sentiments be held universally in the outraged and downtrodden South, though in silence and stillness, until the now far-distant day shall arrive for just retribution for Yankee usurpation, oppression, and atrocious outrages — and for deliverance and vengeance for the now ruined, subjugated, and enslaved Southern States! May the maledictions of every victim to their malignity, press with full weight on the perfidious Yankee people and their perjured rulers—and especially on those of the invading forces who perpetrated, and their leaders and higher authorities who encouraged, directed, or permitted, the unprecedented and generally extended outrages of robbery, rapine, and destruction, and house-burning, all committed contrary to the laws of war on non-combatant residents, and still worse on aged men and helpless women!”

Using a forked stick, Ruffin was ready to pull the trigger and end his life when unexpected visitors came calling. Not wishing to upset his guests, Walther remarks, the Virginian waited for them to depart, and, when they had gone, “returned to his room to finish what he had begun. In the intervening two hours, his determination had increased.” His final diary entry, some of the most spectacular last words ever written: “And now, with my latest writing and utterance, and with what will [be] near to my latest breath, I here repeat, and would willingly proclaim, my unmitigated hatred to Yankee rule — to all political, social, and business connection with Yankees, and to the perfidious, malignant, and vile Yankee race.” He placed the muzzle of his rifle into his mouth and pulled the trigger, but the percussion cap exploded without discharging the shot. Downstairs, Jane Ruffin heard the noise and raced outside to find Edmund, Jr. Before they could get back to stop him, the old man had calmly reloaded his weapon and fired again. Craven wrote that “a shot rang out. The weary old soldier had gone to join the comrades of a Lost Cause.” His children found his lifeless body still sitting upright in its chair, Walther details, “defiant and unyielding even in death.” When Edmund Ruffin, Jr., told his children of their fallen Fire-Eater’s suicide, he told it true: “The Yankees have…killed your Grandfather.” The Old South was dead.

Sources

Craven, Avery O. Edmund Ruffin, Southerner: A Study in Secession (LSU Press, 1982).

Walther, Eric H. The Fire-Eaters (LSU Press, 1992).