A review of The First Congress: How James Madison, George Washington, and a Group of Extraordinary Men Invented the Government (Simon and Schuster, 2016) by Fergus Bordewich

Amateur historians usually write excellent histories. Left unshackled by the latest groupthink of the academy, these historians tend to be independent thinkers and more importantly better writers than their professional counterparts. Shelby Foote used to implore historians to learn to write better. After all, our job is to influence the public, to “interest it intelligently in the past” as G. M. Trevelyan wrote. Popular histories tend to accomplish this needed and worthwhile goal. Most Americans gather their historical knowledge from the amateurs, but when the amateur lacks a comprehensive understanding of the past or has so ingested the propaganda and dogma of his age that his writing suffers from countless mistakes, it brings to mind Polybius’s question, “But if we knowingly write what is false whether for the sake of our country or our friends, or just to be pleasant, what difference is there between us and hack writers?” Fergus Bordewich fits that last description.

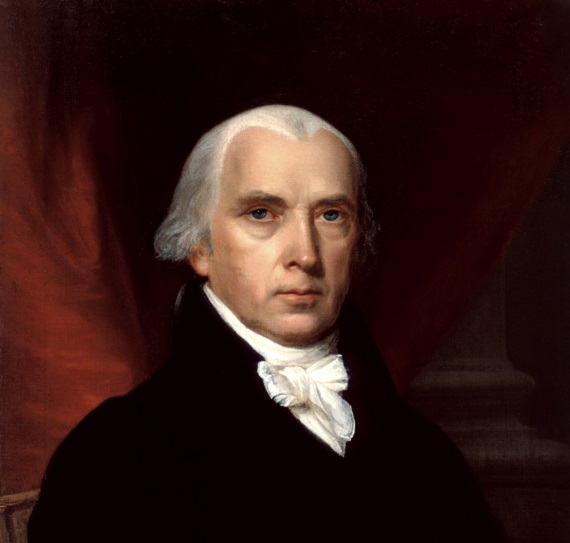

Bordewich writes well. His style is crisp and lacks the pedantry of an academic work, but that is the only benefit to reading his scribblings. A good history on the First Congress was needed. Bordewich correctly asserts that this was perhaps the most important Congress in American history, but to suggest that the First Congress “invented the government” displays a lack of understanding of American history, and more importantly, Bordewich does not seem to be aware that the Constitution’s ratifiers—the proponents or friends of the document—insisted they were not creating a national government but maintaining the federal republic as under the Articles of Confederation. The nationalists that dominated the First Congress perverted the founding. To Bordewich, they saved the “nation” and “breathed life into the Constitution.” As James Madison asserted, the public ratification debates gave the Constitution its life and validity, not the First Congress.

Bordewich makes several mistakes in the book, some embarrassing, others subtle. For example, he claims that John Adams wrote the Lee Resolution urging American independence, insists that James Madison’s reputation “increased during the long campaign for ratification” as a known author of the Federalist essays—he wrote them anonymously and with little overall impact—and portrays opponents of a strong central government as a “small minority.” Southerners, particularly those who attempted to retard the headlong rush toward nationalism, are described as “temperamental,” “hot-tempered,” “stony-faced,” and “haranguing” while Northerners are “brilliant,” “provocative,” “handsome,” “elegant,” and “tireless.”

Bordewich blames Southerners for rampant sectionalism, all to defend slavery, while Northerners get a pass because of their far-reaching nationalist vision and (tepid) commitment for abolition. Of course, Northern nationalism was always a disguise for sectionalism. One of Bordewich’s heroes, Fisher Ames, was a leading New England secessionist after he retired from Congress. Bordewich omitted that from his narrative by instead highlighting his experimental Massachusetts farm. How quaint and incorrect.

There is little doubt that the First Congress transformed the United States. I often tell people that the Constitution died in 1789 with Oliver Ellsworth’s first Judiciary Act. Bordewich considers that legislation to be one of the crown jewels of the First Congress because it ultimately allowed for the modern activist federal court system. He expresses disappointment in Madison’s failure to have his “incorporation amendment” added to the Bill of Rights and argues that Jefferson implicitly approved of such an amendment because of what he later wrote to the Danbury Baptists. In fact, Bordewich fails to understand why the “Antifederalists” insisted on structural amendments, meaning what became the Tenth, while paying very little attention to civil liberties. They did so because they understood without such structural restrictions on central authority, the general government would soon morph into a “national” monstrosity at the expense of the States. This was a more prescient prognostication than anything the “Federalists” proposed during the First Congress. Ellsworth worried his legislation would not last a few years. The Tenth Amendment turned out to a paper tiger while the Judiciary Act became a legal juggernaut.

Bordewich admires Hamilton’s financial plan and delights in the ultimate victory of nationalism over State power. This should be expected. The standard narrative of American has the nationalists as the visionaries, the true believers in the original Constitution, while the “Antifederalists” are the thorny, narrowly provincial trouble makers intent on destroying the United States. This is a magical fairy tale. James Madison did not “evolve away from his early Federalist [sic] roots toward an embrace of states’ rights…” he simply defended the Constitution as ratified by the States in 1788.

The First Congress is a noble idea born from the twenty volume First Federal Congress Project at George Washington University. In more capable hands, it could have been a valuable addition to the historical canon of the early federal republic. As it stands, Bordwich’s tome is better suited to the bargain bin at the local bookstore, a light and at times fun narrative that lacks necessary depth, context, and a comprehensive understanding of the founding period.